Madrid town that built network of illegal tunnels faces one-million-euro fine

Navalcarnero claims cellars are 350 years old, but experts say they are no older than a decade

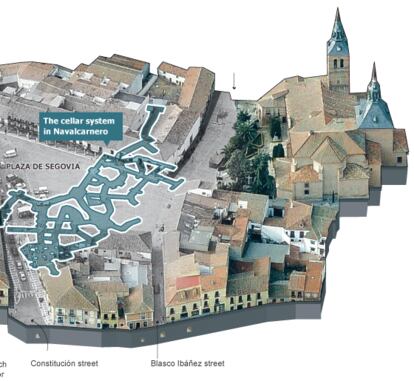

Around two kilometers of tunnels snake underneath the main square in Navalcarnero, a town of 26,000 residents located 30 kilometers southwest of Madrid. Baltasar Santos, who has been the mayor there since 1995, claims that they are 350 years old. But the fact is, they weren’t there a decade ago.

A month after inspecting the tunnels and their potential effects on nearby buildings, experts from the Madrid regional heritage department have reached the same conclusion as local engineers, who had already warned about the effects of carving out such an extensive area without the necessary licenses.

The regional inspectors, who came to see the tunnels in mid-February, “did not find the existence of [historical] cellars” under Plaza de Segovia. “In the event that they existed at a prior time, as the city says [...], they were destroyed as a consequence of digging the new ones.”

The only vestiges that the regional engineers found around the square, which might have been part of old subterranean structures, had no historical connection with the new tunnels, which have been created by Baltasar Santos, of the center-right Popular Party (PP).

The conclusions of the regional government, which is also run by the PP, are not very flattering for Navalcarnero authorities, who drafted a report in 2011 claiming that the underground tunnels were several centuries old. This document was signed by the municipal architect and approved by the town planning councilor.

The report notes that “the current cellars show very few original structural elements”

“The cellars do not date from 2004, the technicians will attest to that,” asserted a local spokesman on Tuesday, before learning of the existence of the regional report. “Anyone, even a layperson, can get a sense of how old they are by looking at details such as the ceilings blackened by the mold that resulted from wine fermentation inside the old cellars.”

Yet the regional report notes that “the current cellars show very few original structural elements,” and that these were used to create “a new, labyrinthine gallery that is being referred to as a cellar and attempts to imitate historical structures.”

Navalcarnero’s modus operandi has led the Madrid department of Employment, Tourism and Culture to initiate infringement proceedings against it for carrying out construction work under the main square “without authorization and with possible damage to the original structure.” The town faces a fine that could be as high as one million euros.

Then again, compared with the level of local debt, which the opposition estimates to be at least 250 million euros, the sanction does not sound like very much. In the meantime, Santos and several members of his team are official targets of the investigation into what is being referred to as the "Cellars Case."

The mayor claims that the work carried out by the city did nothing more than clean, restore and preserve what was already there, and that no new tunnels were built.

The idea was to turn the network of tunnels into a tourist attraction

A document from 1753 shows over 125 cellars in Navalcarnero, and at present there are more than 200 documented cellars in the historical center of town. But the vast majority of them are located under homes, and none under Plaza de Segovia.

“The historical cellars are under old farmer’s and cattlemen’s houses, where they used to keep their products, but they have nothing to do with the ones the mayor built,” notes Juan Benito, of the Popular Democratic Party, which has one representative in the local council (the PP has 12, the Socialists have seven and United Left has one).

Between 2004 and 2011 the local government joined the existing tunnels under the square, most of which had been built by residents under their homes to be used as cellars. It did this with one idea in mind: to turn the resulting network of underground tunnels into a tourist attraction. But it bypassed legal and technical requisites, including a geotechnical exploration. In fact, the government did not even ask for permission from the regional heritage department, a necessary step in an area that enjoys special legal protection as a Cultural Asset (BIC).

The project has been on hold since 2011 under court orders. The opposition suspects that the mayor may have spent over 25 million euros on the cellars, probably by diverting funds earmarked for other municipal projects.

The opposition suspects that the mayor may have spent over 25 million euros on the cellars

On top of this, regional technicians observed structural damage to some of the homes around the main square. One house had cracks that may have been caused by lower ground resistance resulting from the removal of all the earth. Manuel Muñoz, the owner of this property, took photographs of the conveyor belts that were used to take out around 4,200 cubic meters of earth (the equivalent of 700 truckloads) right under his feet. “That’s a lot of earth for some simple cleaning work, isn’t it?” he says, with a touch of sarcasm.

José Luis Adell, the Socialist spokesman and previous mayor of Navalcarnero, is defining the whole thing as “a scandal of biblical proportions. Let us hope we don’t end up like the town in Paint Your Wagon.” In the 1969 movie starring Lee Marvin, Clint Eastwood and Jean Seberg, a gold rush town ends up falling into the ground as a result of all the tunnels running beneath it.

Meanwhile, it is the mayor’s intention to open up the tunnels to the public by the summer.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.