Portrait of a terror tamed

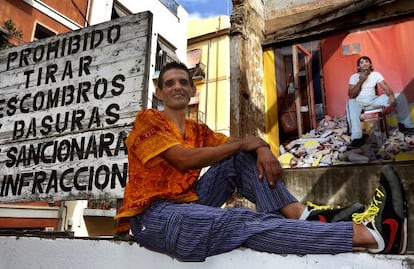

At 14 he robbed banks and smoked heroin Today, Víctor González is a popular resident of El Carmen, Valencia His image is now part of an art installation

After divvying up the haul, he went home to change clothes. He put on a jump suit he had stolen the previous week from a boutique. "When I went down to the street, the cops were waiting for me. It was crazy. I had just robbed a bank with my buddy El Marquitos and we got 1.2 million pesetas [7,200 euros]. But they only wanted me for the boutique holdup." In those days, Víctor González was 16. Now, pushing 40, he remembers his life as a problem street kid, narrating the story in an even, monotonous tone, without a hint of either braggadocio or scorn.

"I never wanted to go to school, or work, and I was hooked on heroin and cocaine... So to pay for my habit I robbed banks, but always with a knife. I wasn't into guns; I never hurt anyone," he explains. González was born, and had his first brushes with the law, in the old Valencia neighborhood of El Carmen, which has lost its bohemian and creative air to creeping gentrification. With his "girlfriend and a friend" he slipped into the back of a jewelry shop by way of an abandoned house. It was his first arrest. He was 14 and didn't go to jail. In those days the neighborhood was a mix of red-light bars, artists' studios, run-down housing and lots left vacant by real estate speculation. It was the 1980s and, as it was across Spain, heroin was ravaging Valencia.

"El Carmen was a lousy place, but nothing compared to Liang Shan Po, where taxi drivers wouldn't take you and the police didn't go," says González, in reference to a tough shantytown on the outskirts of Valencia. Some neighborhood people pass by and greet him, including an off-duty local policeman. González is well known, and generally liked, judging from the tone of the chat.

To pay for my habit I robbed banks, but always with a knife, never a gun"

Besides, his image, blown up to 15 square meters, hangs in a nearby street. It is one of the giant photographs that comprise a project by photographer Luis Montolío, who, on the bare party walls beside lots left vacant by demolitions, has hung huge photos of "interesting" local people, instead of the usual graffiti. "González is a special person, very sincere," explains Montolío, who learned his art from professionals such as Alberto García-Alix and David Alan Harvey, of the Magnum agency.

González had relatives in Liang Shan Po, whose sonorous Oriental name (also applied to several similar shantytowns across Spain) is that of a bandit-infested swamp in The Water Margin , a 1970s Japanese TV series about a band of outlaws in medieval China. "I went to live there for a while. Nobody knew me and I had to make myself respected. I made friends and we began to rob banks. From those days, only one of us is still alive," says the thin, wiry and tattooed González. "When I was 14 they took me to a detox farm; I came out and went back to heroin. My mother even chained me to the bed. It was heavy for her, but she was always there," he says in his slow-paced speech.

He was caught in a hold-up at a bank branch in Montcada, near Valencia, convicted, and appeared on the front page of a local paper. This, his first taste of prison, was at 16. He returned twice, and spent much of the following decade (1991-2001) behind bars. "Inside, I went on doing drugs - heroin, pills, cannabis - because in jail you can get all the drugs you want, if you want them. But I realized I was going nowhere. I looked at myself. I got into a methadone program, and off the habit. Prison is a massive waste of time, but at least I got my head together."

González is a special person, very sincere"

First he was in the old Modelo prison in Valencia, just before they closed it down and the director Luis García Berlanga filmed Todos a la cárcel there. Then he went to the Picassent penitentiary, outside Valencia, before finally requesting a transfer to the prison in Burgos, to get away from his circle of addicts.

He came out, and found a maintenance job at Valencia soccer club's Mestalla stadium. He baked bread for a time, and then worked as a laborer in construction. The crisis burst the construction bubble and González became unemployed. Now he does odd jobs on his own as a housepainter and handyman. He is not as "manic" as he used to be when he "worked his ass off" on the construction site or killed time in prison lifting weights and playing soccer. He no longer wears his hair long, as in the giant photo. He has had health problems, and gets a 68-percent-disability subsidy. "It keeps me going and I can still work half days," says González, glad to be befriended by Montolío and included in his art project.

A nearby photo shows the dance teacher and night-club owner Olga Poliakof, who recently passed away. Further along the street is Fer, clothes designer, waiter and body-art model, dressed up as a heroic sword-and-sorcery videogame warrior, but carrying a poodle instead of some horrific weapon. These are faces of the neighborhood, including that of Montolío himself, whose visage decorates a blank wall beside a demolition site, where, before the crisis, a block of luxury apartments was promised, but so far only offers a varied assortment of garbage.

One can be a good person, though you have a past you can't erase"

González likes the plan to embellish a neighborhood that is still far from rehabilitation, and is the soul of one of the largest historic city centers in Europe. He likes to relate to people. "Sometimes, in a job [i.e. a holdup] you had to take a hostage," he recalls. "Once the hostage was a woman who got really nervous. I got her to sit down on a sofa, and tried to calm her down, telling her that all we wanted was the money from the bank. Then later, in a police line-up, she said she didn't recognize me. I think she did that because I was nice to her," he says with a slight smile.

"I didn't go to school much, and when I did they threw me out. Once I told the principal: 'If you open the door for me, then I won't have to climb out over the wall'." He opened it and pushed me out. But later, when I was in hospital after the Civil Guard arrested me in the bank, Don Antonio, the principal, and his wife came to see me."

When the story touches on his personality these days, he shifts to the third person. Asked as to why his neighbors seem to appreciate him, he suggests: "One can be a good person, though you have a past that can't be erased. One knows how to talk to them, listen to them, be at ease with them."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.