The artful dodger

Leonardo Patterson started selling fake indigenous art from a Costa Rican restaurant He ended up exhibiting in New York with Yoko Ono, until the law caught up with him

Around 35 years ago, in a cozy restaurant in the sultry south of Costa Rica, Leonardo Patterson discovered a goldmine that would form the nucleus of his business dealings. Tourists from Europe, the United States and Canada would listen entranced as the then-thirtysomething detailed his adventures in mountainous jungles and showed them the pieces of indigenous art he had supposedly recovered. Then he would offer to sell them.

Loquacious and easygoing, Patterson played the part of a humble, hardworking businessman when selling the stories he relayed to open-mouthed audiences. Even so, actually making a sale was a triumph in an age of stringent airport checks and the zeal of authorities when it came to protecting cultural heritage. The buyer would return home happy in the knowledge that in a corner of a suitcase lay a small piece of the history of early American civilization. In his restaurant in Puerto Viejo, Patterson would also be satisfied at having lined his pockets - by selling a fake.

Audacious, able and ambitious, Patterson, born in 1942 in Limón province, soon set his sights on greater rewards than the limited range that southern Costa Rica could bestow. So he duly decamped to New York, where he set himself up as a noble savage and began to infiltrate the glitterati of the art, diplomatic and business spheres in order to continue his trade in indigenous pieces, whether they were genuine or not. In 1985 he garnered the support of artist Yoko Ono and actor Michael Caine to stage an exhibition of supposed anthropological and archeological artifacts from the Bribri people, native to his province of Limón.

But Patterson's international wheeler-dealing came to an inglorious end last week when he was tried in a Santiago de Compostela court for smuggling protected heritage on the basis of an exhibition of Pre-Columbian art he organized in 1996, which featured pieces claimed by a variety of nations. He had been arrested in March of this year at Barajas airport in Madrid, and prosecutors have sought a two-year jail sentence and a fine of 60 million euros.

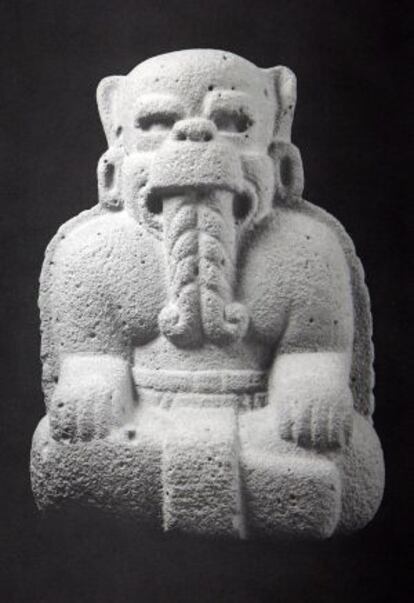

It is a far cry from his lifestyle in New York, the base from where he became, in the words of the authorities in Mexico, Guatemala, Peru and Costa Rica, a smuggler of Pre-Columbian heritage. Patterson was placed on Guatemala's wanted list in 2008 for illegally exporting 269 pieces of Maya archeology for sale in Europe. Costa Rica wants 495 artifacts back from what has become known as the Patterson Collection, which includes 1,800 Pre-Columbian pieces including masks, sculptures, gold, gems and precious stones, valued at over 50 million euros. His trail was left in Mexico, from where he claimed to have removed Olmec artifacts for sale in Germany, which were false despite letters of authenticity from a lawyer and a Costa Rica politician.

In 1985, Patterson was stopped at US customs with a ceramic figure and 32 turtle eggs. "I brought them with me because they are delicious and very nutritious. I didn't know, and I don't think anybody does, that bringing them into the country and eating them is a federal offense in the United States," he said. He was placed on probation.

During the 1990s, he enrolled in the Foreign Service and became a cultural attaché to the United Nations, but Costa Rica revoked his diplomatic status when in 1995 The New York Times published an article linking Patterson with Val Edwards, an alleged trafficker of indigenous art from Mexico and Guatemala. But his fame was secured. The following year he arrived in Galicia and with the backing of a former regional premier he staged an exhibition attended by the former president of Costa Rica and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Óscar Arias Sánchez.

"He is well known because he did not just deal in Pre-Columbian pieces but also works of art, especially Salvador Dalí. But in investigations by the police and art experts it was concluded that many of the pieces were fake. That was the problem, for example, with the exhibition in Santiago," says a Costa Rican diplomat who knew Patterson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.