The tall tale of Agustín Luengo

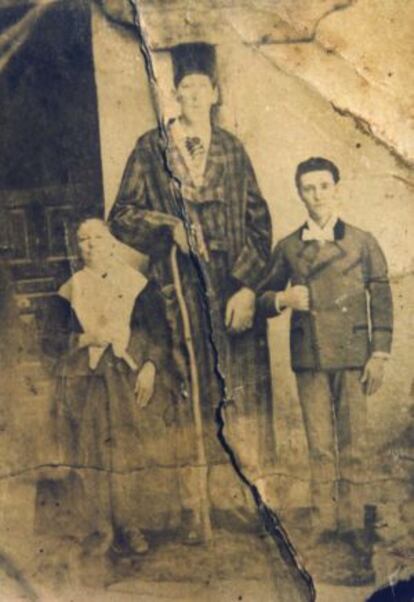

The 2.35-meter Spaniard agreed to sell his body to the Museum of Anthropology The giant wanted to fall in love and raise a family but was viewed as a monster

In Puebla de Alcocer, the Extremadura village where Agustín Luengo was born, there was nothing but derision in store for him. So his father sold him for 70 reales, two loaves of white bread, half an arroba (around 12 pounds) of rice, honey from the Portuguese region of Alentejo, a jar of firewater, two legs of ham and a daguerreotype.

It was not a bad deal, even though the old man would have liked to have made 200 reales out of his son. But he was up against Marrafa, a Portuguese circus owner with a proven talent for negotiation and a sharp eye for the kinds of freaks that peopled his traveling show.

Agustín Luengo was not displeased by the deal. He wanted to see the world and leave behind the tales that exaggerated his size to three meters and depicted him as an eater of live mice who slept at the bottom of a dry well. But his real dream was to fall in love and form a family.

But that would only be if his 2.35-meter frame did not frighten off the girls, who tended to view him as a monster. On top of that, his manhood was proportionately quite small, and gave rise to numerous jests.

This is the unlikely tale of a romantic giant whose life became a horror story through circumstance. There are two main characters in it: a monster halfway between Frankenstein and the elephant man, and a mad scientist — a sinister, visionary man who was so obsessed with embalmment as a form of achieving immortality that he used to take the dead body of his daughter Conchita, decked out in a wedding gown, out for walks.

Luengo achieved fame while he was still alive, chiefly as a circus act but also because he literally stood out from the crowd any time he went out for a walk.

The mad scientist, Pedro González Velasco, founded Madrid’s Anthropology Museum. Chance brought them together forever: the giant’s remains are still on display at the museum, which is located on Plaza de Atocha in Madrid.

Next to Luengo’s bones, there is the life-size mold that Doctor Velasco made of him, explains Luis Folgado de Torres, author of El hombre que compraba gigantes (The man who bought giants).

The minute he laid eyes on the giant man, Velasco understood that his own dream lay within the grasp of those clumsy extremities. It would be the climax to a career that had already earned him the chair of the anatomy department at the Medicine School.

This barefooted human who paraded before him in a private performance organized by Marrafa, the circus owner, for the benefit of King Alfonso XII, would be the kind of world attraction he needed for the museum he had designed, which was inaugurated in April 1875.

Luengo ended up in the arms of La Joaquí, the star attraction of a brothel

The scientist quickly offered Luengo a deal. He wanted the giant to sell him his body. Velasco offered him 3,000 pesetas in the following manner: an advance of 1,500 now and the rest of the money in daily payments of 2.50 pesetas — what a construction worker made in two days back then — until his death.

Luengo could not understand why anybody would offer him what sounded like quite a good deal. He was planning to live for a long time. But Velasco had an edge: he knew that Luengo’s disease, acromegaly, would soon kill him.

But with fresh money in his pocket, Luengo left his circus days behind. It had made him famous, but there were two things he was unhappy about. First, Marrafa made him hide every time they arrived at a new location in order to preserve the surprise factor — especially in a country where the average height barely surpassed 1.50 meters. The second problem was more intimate in nature: he still hadn’t found someone to love.

He thought this would be easier in the capital, even if he had to pay for it. So he left behind the kangaroos, the Bengal tigers, the dwarves who served as a cover for smuggling activities, the constant lice, the trapeze artists and the women who were more eccentric than exotic, to try his luck in another kind of showplace: the Madrid of Benito Pérez Galdós and Valle-Inclán.

It was in this setting that Luengo ended up in the arms of La Joaquí, the star of a brothel run by La Antonia. Rather than love, what La Joaquí was really after was Luengo’s well-lined pockets. And he was very generous with her.

The giant wasted his advance on La Joaquí, thinking he could get her out of the brothel and form a normal-sized family with her. But she resisted, and Luengo ended up rambling down the streets of Madrid alone, a broken-hearted hulk of a man.

To top it all off, osteo-tuberculosis was eating up his bones and nothing seemed able to soothe his pain. The only thing that worked was a hallucinogenic drink made with rye ergot that turned him into an exhibitionist junkie who was willing to fornicate in the middle of the street.

Then, one morning, he collapsed and died on a sidewalk. Velasco didn’t find out until it was too late for his embalming experiment. The body needed to be warm. Although he still attempted to empty the body of its putrefying flesh and leave nothing but the bones, his plans were ruined.

His dream of competing with other European museums for sheer wow effect and of outdoing the embalmments of the Maya and the ancient Egyptians was not to be.

Only the giant’s bones remain. Nobody knows what happened to the skin, which Velasco tore off and kept in the museum attic, where it remained until the 1980s. The Velasco family, which owns both the body and the National Anthropology Museum, holds the answer to that question.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.