The last of Spain’s two-wheelers

Derbi closes its Martorelles plant, ending mass production of motorbikes in the country

It fell to Xavier Canet to give the coup de grâce to Derbi. He pressed the button that shut down forever the assembly line in the motorcycle works at Martorelles, near Barcelona. Canet’s companions chose him on account of the 35 years he has spent there, the second-oldest on the assembly line.

"The oldest one is very shy," explains Canet over the phone. Now he is on vacation, but will soon be back at the factory to collect his severance pay, and that will be that. Another 97 are in his situation. Only a skeleton staff of some 20 will continue working in the factory, to dismantle it. Everyone remembers the last motorcycle that left the plant, bound for Scandinavia, the frame signed by the whole staff.

Since midday on Friday, March 22, 2013, all that remains of the legendary Spanish motorcycle make is a stock of bikes to be sold, and 92 years of history in a country whose passion for two-wheel motoring is borne out every other Sunday in spring and summer when the likes of Jorge Lorenzo and Dani Pedrosa joust for the MotoGP championship.

Piaggio, the owner of Derbi since 2001, has decided to effectively shut down the Spanish motorcycle industry - which has been near-moribund for years after the closures of the Honda and Yamaha factories in the country.

Before the term was in vogue, they were pioneers of low-cost"

"You could see this coming," says Albert Adami, a grandson of the founder of Derbi, Simeó Rabasa, who notes that "the family viewed the closure of the plant as a tragedy -- it was like a family." Adami adds that the death of the make is a reflection of government policies based on tourism and services.

Some 15 years ago the Rabasa family tried to turn Derbi into a multinational by having it made in China, a venture which turned out poorly. In a desperate quest for liquidity in 1998, they had to accept the entry of the risk-capital fund Mercapital. Only three years later, the third Rabasa generation sold the company to the Italian firm Piaggio, a longtime industrial partner and which seemed to represent the only potential lifesaver for Catalan company.

"The Italians arrived with revolutionary ideas. I remember the managing director who came [Leo Mercanti] said that Derbi was a racehorse that had not been fed for years," explains Francisco Cornejo, of the factory union. The revolution lasted only until Piaggi also purchased Aprilia a few years later. Shortly afterward Derbi ceased to make the engine -- the heart -- of its motorcycles. The new option was the high-powered Mulhacen model, which was at odds with a long history devoted to small-displacement bikes. And with the onset of Spain's dire economic crisis in 2008, investment shrank to a trickle. A year ago, Piaggio finally announced the plant's impending closure.

Wheels of time

- 1922. Bicycle repairs.Simeó Rabasa becomes the owner of a bicycle repair shop in Mollet del Vallés. Soon he starts to make machines, including frames for early motorized bikes.

- 1949. First roars. The 48cc Derbi SRS comes to life, with the 1950 Derbi 250, a copy of the Czech Jawa 250, becoming the company's first big success story.

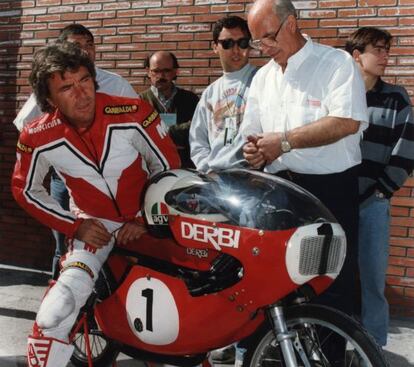

- 1969. Red bullets. Ángel Nieto wins Derbi's first world championship. "I started working in the Martorelles factory when I was 14, beginning by sweeping the floor," he said afterward.

- 1998. End of family. Derbi fails in its Chinese foray and has to look for outside investment. in 2001 Piaggio buys 100 percent of Derbi.

- 2013. Final bullet. The production line is stopped.

Derbi was unequal to this latest challenge. Until then it had met them all, surviving with low-powered machines while its Spanish competitors turned to big bikes. In the late 1950s and 1960s, the advent of a small, cheap Spanish car, the Seat 600, collapsed the market and bankrupted 190 small Spanish motorcycle makers; but Derbi survived because, after all, it was the Seat 600 of bikes. And in the 1980s, with the onslaught of the Japanese, Sanglas and Ossa (makers of bigger bikes) also went under.

Derbi, which sold utility bikes for the equivalent of three months' average wage, kept going. "Before the term was in vogue, they were pioneers of low-cost," says Estanislau Soler, of the Motorcycle Museum.

But more recently, there has been no way to compete against cheap bikes from Asia. Nothing is left, either, of the clout the company used to have in the Spanish government, when, for example, in 1995 it obtained the suppression of a licensing tax for bikes with engines smaller than 125cc, to the fury of the competition.

"The entry of Japanese firms to produce in Spain was at first very unsportingly received by Derbi," says Jorge Lasheras, a former executive of Yamaha in Spain. "Their first reaction was to set up barriers to the Japanese, to armor-plate the market."

It was ironic that Andreu Rabasa, an advocate of protectionism, was reluctant to do what he had long done on the racetrack: compete. Though he was good at it. This was where Derbi earned the “red bullet” nickname, and 18 world championships.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.