Cartagena to host treasure trove

Half a million coins were recovered from the wreck of a 19th-century frigate The Nuestra Señora de la Mercedes haul is to be housed at the Underwater Archeology Museum

The 14.5 tons of treasure recovered from a 19th-century Spanish frigate by US deep-sea salvage company Odyssey Marine Exploration have found a permanent home at the National Museum of Underwater Archeology (ARQUA) in the port city of Cartagena.

The haul of almost 600,000 pieces of gold and silver coinage, worth about $500 million, was recovered from Nuestra Señora de la Mercedes in 2007 off the coast of Portugal and soon became the subject of a fierce legal feud as Odyssey's owners fought to keep it in the United States and Spain battled to have it returned.

"The treasure will not be broken up because we consider the frigate's cargo to be a cultural asset," says Jesús Prieto, the director general for Fine Arts and Heritage.

Prieto said ARQUA was chosen over other museums keen to exhibit the coinage because of its specialist laboratories and staff, who will be tasked with conserving and restoring the coinage, as well as its spacious installations, which will be adapted to hold the permanent display of 212 gold coins, or pieces of eight; 309,184 silver coins; and 265,157 metal coins that have fused together.

Our right to know about our past

This was no ordinary treasure trove. When deep-sea salvage company Odyssey Marine Exploration announced in May 2007 that it had discovered half a million gold, silver and tin coins, it knew the risk it was taking. If US judges ruled it could keep the find, it would have carte blanche to search other wrecks on the seabed in international waters and, regardless of the nationality of the vessels, sell whatever it found.

But it wasn't to be. A Miami court ruled in the Spanish government's favor, and the US Supreme Court refused an appeal. The Spanish had argued from the start that the coins had been taken from the Nuestra Señora de la Mercedes, a Spanish warship sunk by the British in 1804.

If Odyssey wants to continue exploring for sunken vessels, it now has little option but to hire its services out to governments interested in recovering the contents of shipwrecks. The legal wrangle has robbed the company of any credibility among marine archeologists, who are deeply suspicious of its for-profit motive. The company's other option is to use its highly sophisticated underwater technology to extract minerals and precious stones from the seabed.

The Nuestra Señora de la Mercedes case sets a legal precedent, providing Spain with the mechanisms and procedures to protect hundreds of its vessels sunk in centuries past and now lying on the seabed around the world.

The question now is what to do with those hundreds of sunken ships. Many marine archeologists say they should be left untouched until the technology is developed to allow us to see them in situ. Others say this is merely a justification for not tackling the central issue of finding funding to explore or rescue them.

That question in turn raises the issue of whether archeology is to be funded privately or publicly. Given the interest in Spanish shipwrecks shown by the Odyssey case, it seems absurd to leave vessels on the seabed where nobody can see them. If Spain cannot or will not, for financial reasons or otherwise, recover the contents of these ships, then who will? After all, we have a right to know about our past.

Most of the coins bear the images of Bourbon monarchs Carlos III and Carlos IV and were issued between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. The pieces were struck at the royal mints of Lima, Potisi, Popoyan and Santiago de Chile.

Spain, under occupation by Napoleon's forces, needed the treasure to pay France. Britain, which was at war with France, had told Spain that it considered French financial support as grounds for attacking Spanish forces. When the Spanish convoy carrying the treasure refused to surrender, the British opened fire. The vessel was sunk in 1804 as it neared the port of Cadiz, sending the bounty and the ship's 200 crew and passengers to the seafloor.

Despite laws that prohibit treasure hunters from excavating foreign military vessels, Odyssey took the treasure back to the United States. The coins were recovered from a depth of 1,100 meters using robots. Odyssey claimed they did not belong to an identifiable wreck, but had been scattered across the seabed.

Since a Miami court ruled that the coins be returned to Spain in February 2012, they have been kept in water-filled plastic containers at secure vaults at the Culture Ministry in Madrid.

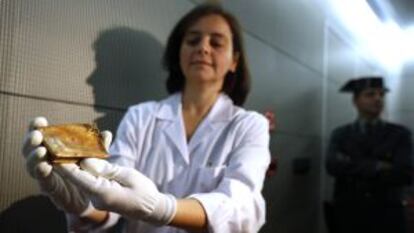

They have now been sent to Cartagena, along with other material that Odyssey found, including metal buttons, buckles, cutlery, and other metal items. A team of specialist conservation staff at ARQUA has been working since the summer on an initial batch of coins and artifacts.

The 5,138 coins that Odyssey had already restored have been kept at the National Museum of Archeology. Prieto says the coins had already been packaged for sale. The Culture Ministry says the public will be able to see the horde from the second half of this year.

The controversy surrounding the recovery has highlighted the number of Spanish wrecks lying on the seabed off the coast of the Americas, Spain and the Philippines. There are an estimated 850 ships lying in the bay of Cadiz alone, many containing gold.

"After this, nothing will be the same. Spain has changed the situation regarding the content of the many wrecks lying on the floors of the world's oceans," says Felipe Viera Castro, a Portuguese archeologist who specializes in maritime history.

Melinda J. MacConnel, vice president of and general counsel for Odyssey, which is based in Tampa, said the forced return of the trove to Spain was in fact "a sad day for Spanish cultural heritage." She said in a statement that Spain had been "very shortsighted in this case," because it "failed to consider that in the future no one will be incentivized to report underwater finds." She predicted that "anything found with a potential Spanish interest will be hidden or even worse, melted down or sold on eBay."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.