"Inside my body is an able-bodied soul"

'La Asturianita' managed to overcome her disability and use it to her advantage

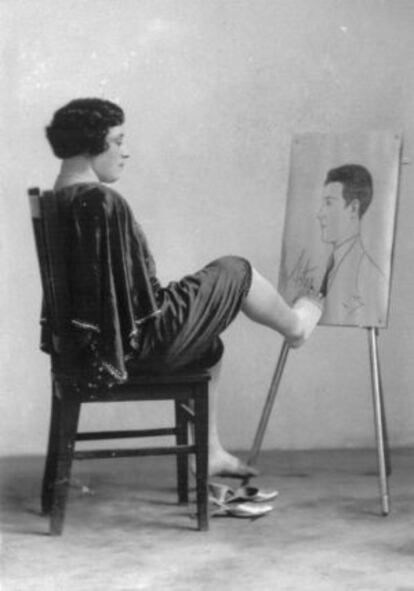

"This is the most amazing case of human recreation through personal willpower. She is the artist without arms - doesn't have them, doesn't need them! She shoots on target. She plays the piano, the violin, the accordion and the xylophone. She teaches calligraphy. She is an excellent typist. She plays pool and cards. She drives a car with her feet. She draws caricatures of audience members. She performs all sorts of womanly tasks: she cuts fabric, pulls threads through needles, sews..."

So read a 1933 poster advertising a Catalan theater performance by Regina García López, also known as "La Asturianita," an eccentric woman who led a life right off the pages of a movie script.

Regina García, the second of eight siblings, was born in 1898 in Valtravieso, an Asturian hamlet with 25 homes and 63 residents. Both her arms were ripped off in an accident at her father's sawmill when she was nine years old. An Asturian who had made his fortune in Argentina offered to pay for her education at Colegio del Asilo, where the best families in Luarca took their children. Later, he wanted to adopt her and take her to Buenos Aires, but her parents refused. They even hired a German specialist to attach mechanical arms to her, but the experiment did not work.

When Regina turned 15, she was told that she had to make room for another girl at school. By then, she had decided that she wanted to be a schoolmistress.

"People would ask her, 'How can you be a schoolmistress without any arms? Forget it! Just sleep, eat and pray'," recalls her son Marcelino, who is 86. "Soon after that she tried to commit suicide by jumping off a cliff."

"She tried sketching with her feet. People thought she was crazy," says her son

That day, on her way back home, she saw some circus performers with monkeys who were picking things up with their feet. "My mother thought, 'If they can do it, so can I.' And she tried sketching with her feet. People thought she was crazy."

That was the first of many times that people would say she was mad. But Regina was destined to tour the world and get rich on the strength of that madness.

She debuted at Teatro Jovellanos in Gijón, performing for Princess María Teresa de Borbón in 1917, and over the following years she toured 42 countries with her show, including Turkey, Egypt, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela and the United States. Notably, she always performed in theaters, never at circuses.

In 1933, La Asturianita met with US President Roosevelt at the White House, where she arrived using her usual mode of transport: driving with her feet. According to the account provided by her daughter-in-law María Teresa Bertelloni in her biography Regina García López, La Asturianita , the president instinctively tried to shake her hand. La Asturianita offered him her foot.

She was imprisoned by both the Republic and Franco's regime, accused of spying

It was during one of her performances, in Avilés, that Regina met the admirer who would later become her husband. They got married in 1922 and had three children: María, Marcelino and Juan. In 1928 they separated.

"My mother had a steamroller personality. She was very intelligent, and men back then wanted to act like women's tutors," explains Marcelino. "The same thing that attracted him to her was what tore them apart. I get the impression that my father felt overwhelmed by her."

On March 27, 1936, before her performance at a theater in Luarca, Regina talked about her life. "Children ran away from me... I had my first revelations about compassion, which wounds and humiliates. People would look down on me piously. 'Poor little armless girl! And such a burden to her family!' This embittered my spirit. I turned my will into action, and learned, worked, earned, spent, dreamed, loved and accomplished things, because inside my mutilated body there is the soul of an able-bodied woman..." And then she introduced her great project, Selección, aimed at raising funds during her tours to sponsor smart village kids with no means of getting an education.

She was harshly criticized over that project, as Luis González Fernández writes in Regina, el coraje de una mujer (or, Regina, a woman's courage). But newspaper La Voz de Asturias praised her: "She is exceptionally cultured and she is passionate about teaching. [...] Do not view her as a cabaret number, simply view her as Regina García: selfless, philanthropist, apostle."

Regina was indeed cultured, speaking five languages: Portuguese, French, English, German and Italian. That is why the information chief at the War Ministry, Ángel Pedrero, proposed that she move to France and spy for the Spanish Republic. Regina refused. She had arrived in Madrid shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War with a contract at La Zarzuela theater to raise funds for the children of Luarca. In April 1937, she was jailed at Ventas penitentiary on charges of spying for Franco's side.

When Madrid fell to the Nationalists on April 1, 1939, Regina was freed. To celebrate her release, she went to the movies. She was wearing a cape-dress that concealed her disability, and when the movie ended she was the only person in the room to not make the Fascist salute. "Arm in the air!" shouted a Falangist. "I don't raise my arms even if Franco himself asks me to," she retorted. "In that case, you're under arrest."

She recounted this incident herself in her diary. "My mother never kept quiet," says her son Marcelino. "She protested without thinking about the consequences. She was very temperamental."

Regina finally showed the Falangist that she had no arms and explained that she had just been released from jail, where the Republicans put her. She was let go, but shortly afterwards the new regime also asked her to spy on the other side. Again, Regina refused. And again, she was jailed. During her second stay, Regina was taken to the psychiatrist's office on several occasions. Her diary explains how she suffered from hallucinations. "I gradually lose track of everything and the noises in my imagination are completely different from what they should be..."

At her eight-hour trial in March 1942 she was accused of "creating a vast international organization she calls Selección, of masonic inspiration." She was also described as "quite dangerous." Military health officials said she was lucid but suffering from a form of paranoia, seeing herself as the victim of a plot. The attorney asked for the death sentence, but she was eventually acquitted and sent to a psychiatric institution, where she died on May 19 of the same year, aged 44. The Franco regime seized all her assets. Her son Marcelino doesn't believe she died of typhus, as they were told, but was poisoned.

"She was not crazy, but she was not your average woman."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.