"I know what hunger means"

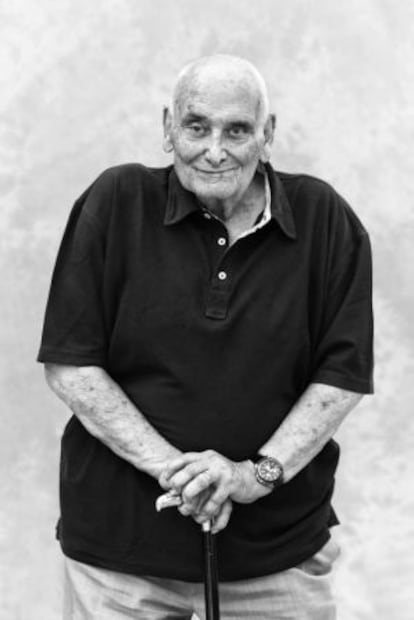

Swimmer Isidoro Pérez looks back on his experiences at the 1948 London Olympic Games

Isidoro Pérez is no ordinary Olympian. Back in the dark days of the late 1940s, when Spain was still recovering from the Civil War, and was isolated from the rest of Europe, he realized that sport was the way to survive. As a result, he was able to briefly escape from the hunger and misery of Spain in 1948, and join 61 other Spaniards - all men - travelling to London to take part in the Olympic Games. Today, the 84-year-old still remembers with pride the bronze medal he won, and how sport changed his life.

"I was aged just 20, and had grown up during the war; all I had known was privation, hunger, rationing. In Spain everything was restricted, but in London, it was like being in another world," he says. "We were there for 20 days and we could go where we liked. We were young, and so we went out late at night, and we met lots and lots of people. I even managed to get a girlfriend," he says, grinning.

Not that Londoners thought much of the quality of life in the capital at the time. Things were tough, and rationing was still in force. The last Games had been held in Berlin, in 1936, and although the symbolism was important, Britain was still recovering from the war; there was bomb damage everywhere, and a shortage of housing.

In Spain everything was restricted; in London, it was like another world"

"The houses were all blown to pieces, but do you know what we really noticed most of all? Everywhere was clean and tidy. They had cleaned up all the rubble, so that all that was left were the ruined houses. Londoners were quite hostile, they weren't really very welcoming, they had their own problems to deal with. They were polite, and rather formal. It was clear that this was something that they had to do, and so they got on with it. But there was no sense that they were pleased to see you."

Athletes were housed in military bases, although Isidoro says that he found the accommodation far better than anything he had known at home.

"They were like enormous parks, with trees, and grass. It was very pleasant. They looked after us, and gave us sandwiches when we went out for the day and wouldn't be able to come back for lunch."

Isidoro is the only survivor from the six-man swimming team, which he says was overshadowed by the US and Japanese competitors. The majority of the Spanish athletes were members of the armed forces, and only the water polo players seemed interested in going out to explore the city in the evenings.

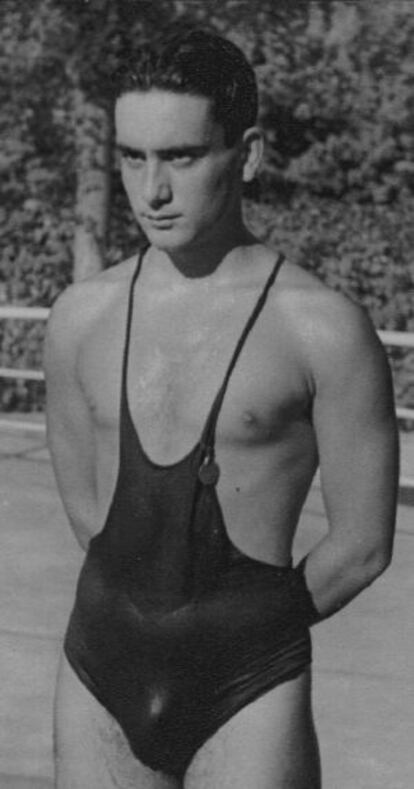

Isidoro says that he had only begun swimming five years earlier, at a covered pool in the Manzanares river, on the outskirts of Madrid. "It was freezing, even in summer. But I didn't care. I was determined to make something of my life. I was determined, and for some reason, I liked swimming. It wasn't a popular sport at the time. I think that most people associated it with the Tarzan films of Johnny Weissmüller." The actor had won gold at the Paris and Amsterdam Olympics in 1924 and 1928 respectively.

Isidoro showed promise and decided to focus on the 100m freestyle. In London he swam in the 400m and the relay. He says that his training program consisted of swimming a kilometer a day, which took him around 45 minutes, followed up by a workout in the gym. A far cry from the specialist training programs that athletes follow these days, he notes.

Isidoro says that swimming allowed him to leave the war behind, and to help heal the scars of the conflict. "I was just a kid when the war started. It stole my childhood and my youth. I was an adult by the time I was 15," he says, adding: "I had seen more than my share of dead bodies and ducked plenty of bullets."

Even after the war ended, the suffering continued, Isidoro says: "There was no food to be found anywhere. I know what hunger means. I have gone to bed so many times dreaming of hunger. I was able to train because I was mentally strong, and my body did what I wanted it to do. Sport was an escape route."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.