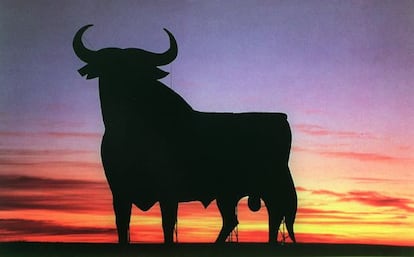

Is the sun setting on Spain as a brand?

The crisis has taken its toll on the country, leading to a resurgence of tired clichés about wine and flamenco and the punishment of Spanish companies abroad

If you look it up in the archives, the expression marca España, or Spanish brand, appeared in this newspaper for the first time in 1985, in a column written from the United States by writer, journalist and economist Vicente Verdú. In it, he predicted that the country would soon be in vogue. "Spain is an entire world ready to be sold," he wrote. The Catalans were promoting their cavas abroad, and La Rioja wines and Lladro figurines were establishing a presence in international markets. Nancy Reagan was photographed dancing flamenco on an official visit to Madrid. "Everything counts in defining a brand, but it's also crucial to break away from the old stereotypes of Easter week and Hemingway to offer something new and surprising," said Verdú.

This period was followed by the Barcelona Olympic Games, which marked the beginning of the internationalization of larger Spanish companies and a period of economic development that turned Spain into a positive example for countries joining the European Union. Per capita income reached the EU 15 average, the population swelled by six million people, the number of universities skyrocketed and for 14 consecutive years, starting in 1995, the economy grew by an average of 3.5 percent a year. The grand finale was the housing boom, when international experts officially christened Spain's "economic miracle."

Now, Spain is in its fourth year of crisis, with 5.5 million people unemployed and a second recessionary dip. The economy is also witnessing the deterioration of the intangible: its brand. This can be seen in concrete figures in the financial markets but also in more indeterminate aspects, such as the reemergence of the old clichéd images of wine and flamenco, or in the disdain of European leaders such as Nicolas Sarkozy and Mario Monti for their Spanish neighbor. Spain is no longer in vogue; Spain is trading low.

"Nobody wants to be like Spain now. Spain is only good for flamenco and red wine," Richard A. Boucher, the deputy secretary general of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), said a few weeks ago. He made the comments at a seminar in Marseille organized by NATO's Parliamentary Assembly, and in the presence of Socialist lawmaker Diego López Garrido, the Spanish representative in the forum. "At a cocktail gathering later, representatives of various countries, including Canada, Germany, Portugal and France, approached me to express their condemnation of his words, and Boucher later sent a letter of apology. There is a disparity between Spain's economic woes and the deterioration of the country's international image, of its credibility, and this loss of prestige is costing us a lot of money," says López Garrido, former secretary of state for the European Union. Garrido called for greater "non-partisan solidarity" in defense of Spain.

Even if your company is solid, you are penalized for the Spain name"

Along with the bursting of the credit bubble, trade relations have also been marked by a feeling that there has been some kind of rupture in Spain's golden image, following a period of economic fortune that even included sports victories.

"In the past, we let ourselves get carried away by euphoria; we were the apple of the world's eye. But now we are at the other extreme," says Miguel Otero, director of the Leading Brands of Spain Forum, an institution formed by the government and large Spanish companies. But he doesn't approve of half-measures. "What needs fixing is not the country's image, but its real problems; with what is happening here, it's difficult to go abroad and change perceptions."

In 2008, the Financial Times included Spain in the PIIGS countries, an acronym for Portugal, Ireland, and later Italy, Greece and Spain, and wrote that the flying pigs were now mired in the muck. "It wasn't an insult, it was a classification, and the problem wasn't that they called us that, but that we were in the group," says Otero.

He stresses, however, the need to highlight the positive aspects of the economy in order to prove that not everything was a mirage, such as the global expansion of big groups such as Inditex and Mango. Unfortunately, these highly publicized commercial successes mask the fact that, in general, the Spanish business world, which is comprised mainly of small and medium enterprise, still has a long way to go in terms of its internationalization. "Exports per capita in Spain total $5,400 [3,300 euros] versus $9,500 in Italy [5,800 euros] and $16,000 [9,800 euros] in Germany," Otero points out.

What needs fixing is not the country's image, but its real problems"

Selling Spain today is not easy. And nobody checks the faint pulse of flagging international confidence more often than those in charge of investor relations departments, who are tasked with promoting the benefits of Spanish firms abroad. "We are taking a beating. Even though your company is on a solid footing, you are penalized for the Spain name. Even if you offer a fantastic deal, you are penalized by investors. The worst part is that they don't consider Spain a country suitable for investment; they have ruled out the possibility of putting money into this country," says the head of investor relations for one large Spanish corporation.

International investment funds have changed their tune significantly over the past few years. "Now, 60 percent of our meetings are focused on macroeconomic issues; we bring analysts who specialize in these subjects with us to meetings. Nobody wants to hear about investment returns in 2014; there is a lot of mistrust with regard to the medium term," he adds.

The finger of blame for this mistrust can be pointed in a very specific direction: the stock market and government bonds. The Spanish bourse has fallen more this year than it did in all of 2011 (more than 18 percent), placing it among the worst-performing in the world. And 10-year government bonds are currently trading with a yield of six percent, more than 400 basis points (or four percentage points) above the benchmark German bond. In 2007, Spain's risk premium - which acts as a barometer for measuring the creditworthiness of a country's economy - averaged 8 basis points.

Daniel Gros, director of the Brussels think-tank, CEPS, warns that "the international perception of Spain has suffered a blow because the country's government avoided acknowledging the extent of the housing bubble. Initially, the banking sector had a very strong image, but this has also been tainted because there are new losses every year." Moreover, "the new government botched the communication of its fiscal adjustment plans."

The government botched the communication of its fiscal plans"

For Gros, "the banking system must be cleaned up as soon as possible; realistic housing prices must be set, ones that are lower than the current ones; the labor market must apply the reforms; and the government must fulfill the promises it has made to its partners."

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs also believes the moment has arrived for economic diplomacy. The agency plans to present a new marketing strategy aimed at polishing up Spain's tarnished image abroad in an official act presided over by the king. Ambassadors are to receive new training in foreign trade, and embassies will be instructed to provide greater attention to Spanish companies abroad. "The idea is that all the different bodies and all their activities are aimed at promoting the Spain brand," sources at the ministry explain. The project also includes the appointment of a special commissioner for the Spain brand. Originally scheduled for a couple of weeks ago, the presentation was postponed due to the budgetary debate in parliament. Now the government is waiting for the king to recover from his hip operation before going ahead.

The Elcano Royal Institute, which has just published its first global presence index (based on 2010 figures), says that Spain ranks ninth in the world as a foreign investor. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has just witnessed Argentina's nationalization of Repsol's subsidiary in that country, YPF, and not long after, Bolivia announced the nationalization of the subsidiary of Spain's national electric company there. When announcing her country's move, Argentinean President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner made a mocking reference to an elephant's trunk, in light of the scandal over the king of Spain's hunting trip to Botswana, where he ended up breaking his hip.

Madrid is, undoubtedly, going through a rough patch with its partners. During his failed re-election campaign, Nicolas Sarkozy used Spain as a bad example several times. "Look at the state of Spain after seven years of socialism," the then-president and candidate declared at the beginning of April. Sarkozy also spoke of "the major crisis in confidence that the great country of Spain finds itself embroiled in now," adding: "There is not a single French citizen who wants to go through what Greece did, and what Spain is experiencing right now." More friendly fire came from a country also experiencing serious budgetary imbalances: Italy. The country's prime minister, technocrat Mario Monti (who is becoming more political with each passing day) blamed Spain for Italy's risk premium problems.

Raphael Minder, Spain and Portugal correspondent for The International Herald Tribune, lived in Spain in the 1990s, returning again in April 2010. "I don't think that Spain is an isolated case, but due to the size of its economy, it causes more concern than Ireland, for example," he says. "But north-south stereotypes are not really useful in this matter: Holland has also stirred doubts," he says, in reference to the Liberal-Christian democrat government losing the backing of the far right for cuts designed to help the country reach its budget deficit target.

Spain's economic instability is not an issue of perception. But it is a reality, and the economic figures refuse to budge. "The perception abroad is really no different than that in Spain: optimism is fast disappearing," adds Minder.

It's true that the crisis of confidence is also palpable inside Spain's borders: consumer spending is in free-fall, credit has dried up, and Spaniards, a society already given to self-flagellation, are seeing that their economic splendor had feet of clay.

Víctor García de la Concha says he has not noticed a fall in Spain's prestige. Since he was appointed to head up the Cervantes Institute more than two months ago, he has receiving countless invitations to set up centers in other countries. "There is no indication of a negative country image at all; it is buffered by the general European crisis and the fact that there are still bugs in the EU system that need to be worked out," he says. He adds, however, that "there is a need to transmit a new, different message in Latin America, which is based on common culture and interests."

"Spain's reputation, which can be understood as admiration, respect and trust toward our country by citizens of the G8 countries, fell between 2010 and 2011, but it is still quite strong, and comparable with neighboring countries such as Great Britain and Italy," says Fernando Prado, Spain director for the Reputation Institute, a global reputation management consultancy. He warns, however, that though Spain "is still strong in soft qualities such as lifestyle, friendly people, and leisure, entertainment and cultural offerings, there are weaknesses in hard qualities such as innovative capacity, technological development, brands, and well-known and successful companies."

Which is to say that there is a need now, like the one Verdú described in 1985, for Spain to put a new spin on what it has to offer, one that brings it back into the global embrace and puts it in vogue once more. Marketing and diplomacy, however, need the backing of an economy that regains its ability to inspire confidence.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.