"I, priest and sinner, ask forgiveness"

Navarrese priests were the pioneers of historical memory, despite stiff opposition from the Church

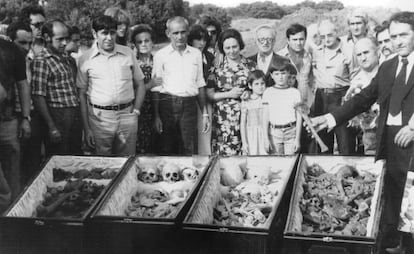

They didn't want to wait any longer. Upon the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, a group of widows, sons and daughters of men executed by Nationalist forces began to search for the mass grave where they had been buried. In Navarre and La Rioja, kneeling on the ground with no tools other than a shovel and their bare hands, they were accompanied by priests, such as Victorino Aranguren, Eloy Fernández, Dionisio Lesaca and Vicente Ilzarbe, who helped the grieving widows to disinter their husbands and who, during the funerals held in their honor, asked for forgiveness for the conduct of the Church during the Civil War.

"This blood was also on our hands." "If we say we have not sinned, we make a liar of God." "From here I, priest, although a sinner, ask your forgiveness in the name of the Church..."

"I took part in many exhumations. It was very powerful. The widows said, 'This is my husband, he was a little clumsy;' 'This other one is my husband, I gave him this medallion...'" recalls Victorino Aranguren, now 80 years old. "They kissed the bones as though they were relics and they asked me to kiss them as well. All of them had a hole in the skull from the coup de grâce."

It was called Operation Rescue. "It surprised us. We took advantage of the beginning of democracy to do something we had wanted to do for a long time," says Aranguren. In September, 1971 a first attempt had been made to make the Church "recognize the harm it had caused and ask for forgiveness" at the Joint Assembly of Bishops and Priests in Madrid. Aranguren penned the proposal, which did not achieve enough votes to go ahead.

The clerics behind the motion received abusive letters "from laymen and priests," notes Aranguren. "They called us swine. Other priests told us they thought it was a lie that we did not justify the war of 1936. Many of them were convinced it was a crusade [in a combined pastoral in 1937, the bishops declared the military coup "a religious crusade to save Spain"]. After the war there was a resurgence in religious practice, which from my viewpoint was a little misleading. The bishops were blind. They did not see the lack of freedom. The Church always runs the danger of resting on power, and it did so greatly under Franco."

At that 1971 assembly, this group of Navarrese priests spoke of the right to meet, the right to associate... "Franco forbade the second edition of the book that came out of that assembly because it said that in Spain human rights were being violated."

They kissed the bones like relics and they asked me to kiss them as well"

In 1974 the historians Víctor Manuel Arbeloa and José María Jimeno Jurío were entrusted with a list of people shot in Navarre. Later they created a commission composed of priests and family members. "We went to visit the widows, to tell them that we could recover the remains and hold a funeral and we saw families that were terrified, absolutely humiliated and afraid to talk even among themselves about what had happened," says Aranguren.

On occasion, the priests even spoke to the killers. Aranguren recalls that after a funeral, during which he had said that not all the executed men they sought had been found, one of the gunmen approached him. "He came to see me at 3am. 'I was there,' he told me. "That night, with a lantern, he took me to the site where the man we were looking for was buried. He had his hands bound with wire."

Up to 1981, these joint commissions recovered the remains of 3,501 people executed across 56 villages in Navarre and 10 in La Rioja. They were buried in cemeteries where they were given "monuments very similar to those erected for the Nationalist dead, who had been elevated to the category of heroes and martyrs while those executed on the leftist side were forgotten," says Jesús Equiza.

In Arnedo, La Rioja, the parish roundly refused to take part in anything similar. "And it was the Navarrese priests who helped us to have the funeral," recalls José Urbano Muro, the grandson of a man who was executed. "We recovered the remains of 51 executed people. The killers were our neighbors. On the day of the funeral, we walked through the village and people pulled their shutters down when the coffins went past. There was still a lot of fear."

Those who carried out the Cervera del Río Alhama massacre were also locals, among them three women and a 15-year-old boy. Among the victims was the grandfather of José Vidorreta, who was six months old at the time. "The priest Tomás Navarro helped us to move the remains and he gave a very emotional speech in the village square. He helped us, but the priests in La Rioja did nothing to stop the massacres. Quite the opposite."

When the exhumations and funerals had ended, Aranguren, Dionisio Lesaca and Eloy Fernández published an article in a Christian magazine called History of an ignominy and of a somewhat tardy restoration. "We keenly felt the long silence of the Church. Those men were not bad, they had noble Republican ideals and they were unjustly killed. How much pain we sensed among those families because they saw how the hierarchical Spanish Church supported the Civil War, identified itself with the rebellion against the Republic and did not prevent these deaths. And because it was these thugs who frequented the churches and cast themselves as good people and Catholics, sometimes friends of the priests. No. The Civil War of 1936 was not a religious crusade... It was fundamentally a fight of opposing economic interests,

In 1971 attempts were made to make the Church "recognize the harm it caused"

brutally cutting short a social revolution that, correcting for deficiencies, might have led to a more just society."

They were the exception. They still are. The president of the Episcopal Conference, Antonio María Rouco Varela, is against the Historical Memory Law: "If they had done in every Spanish province what was done in Navarre and La Rioja, today there would not be so many full graves and ditches," says Aranguren. "The fact that they remain there is a humiliation, and an obligation on society to remove them. Many bishops believe that this matter should not be touched, that it reopens wounds, when exactly the opposite is true."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.