"I've been a solitary hunter"

Rafael Sanz Lobato reflects on shyness, the search for exceptional images and old age

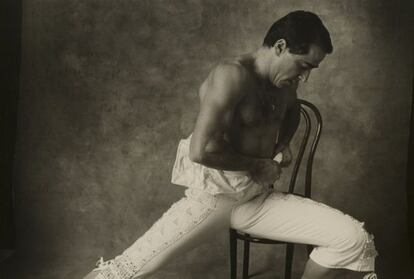

He is practically a legend among the great family of Spanish photographers. Yet Rafael Sanz Lobato, 79, has lived in an ostracism broken only by the National Photography Award, which he received last year in recognition of "his way of narrating the transformation of the traditional, rural world and for his influence on contemporary photojournalism."

Lobato lives alone in a leaky, third-floor walkup apartment in downtown Madrid. Both his eyes are affected by a degenerative disease, and he uses two powerful magnifying glasses as well as a special device to read and to make out the details in some of his work. The walls of the apartment are filled with the series that he has made throughout his life, and which have only gone on display on rare occasions: Easter processions in Bercianos de Aliste, old women in Las Hurdes, bullfighters, or the more recent series inspired by Man Ray and Morandi.

Rafael Sanz Lobato, a left-wing republican who likes to speak his mind, talks against a backdrop of Baroque music as he chain-smokes pipe-tobacco cigarettes.

"I will die with one of these little joints in my mouth, after dining on a good plate of beans from El Barco. That's the way I'd like to go," he says.

One might say that his work has always moved in the shadows of clandestinity. "At the bottom of it all, there's a succession of unfortunate stories. My first conflict was at Arte Fotográfico, the magazine that ruled over Spanish photographic life until 1980, the only redoubt where you could find a different type of photography. It was controlled by the Royal Photographic Society of Madrid, which I joined in 1962, and I kept having arguments with [chairman] Gerardo Vielba. Later, in the 1980s, other centers for creative photography cropped up."

Back then, so-called creative photographers networked through associations and hoped to make their work known to specialized magazines. In Madrid, there was an entire school of creative photographers; Lobato joined a group called La Colmena.

"I'd been shooting for 10 years, but hadn't dared try documentary work. I was too shy. I was 30 and I'd only taken family pictures - a few portraits, little things. I thought that by joining La Colmena everything would be easier, but no." Lobato discovered his own fascination for documentary photography through the foreign magazines that a cousin used to mail him.

He wanted to do the same things, but he felt genuine panic just thinking about standing in front of other people to take their picture. So he joined society members who went out in their cars to towns near Madrid on Sunday mornings.

"There were eight of us in two cars. Right after parking they all sped away shooting their cameras like crazy. I was in shock. I slowly walked to where some children were being photographed to death by my colleagues. Later they did the same with two old ladies. There was no need to ask for permission, and people did not seem to mind. All my panic melted away. I was able to work normally. I soon bought a Seat 600 and was able to go off on my own."

He spent the next 15 or 16 years driving all over rural Spain on weekends (on weekdays he worked for a US compression device firm) conducting anthropological photography. Although he was married and had two children, his family never went with him. Did that not create tension with his wife? "I don't know. The fact is I'm all alone now, and I've had five partners."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.