A picaresque life amid the halls of power

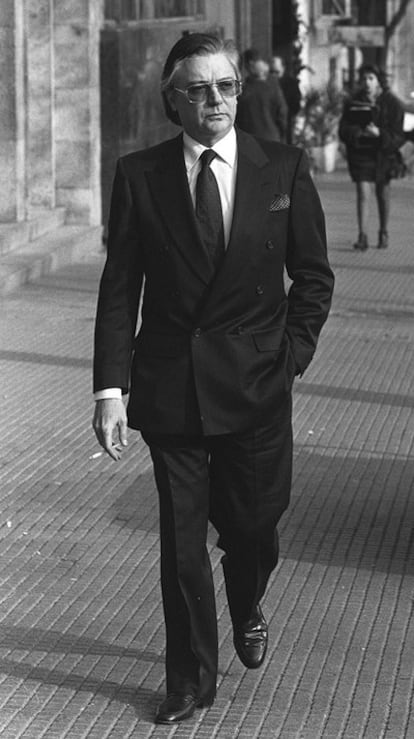

At 75, Francisco Paesa Sánchez is once again in the spotlight, accused of stealing 10 million euros from a Russian magnate

At 3pm on a winter's afternoon just before Christmas, the Confiserie Namur on rue Bitburg in the heart of Luxembourg is full of exclusive customers enjoying the venerable establishment's famed cakes and pastries. Up on the first floor, an elegantly dressed woman in her early forties, wearing dark glasses, is seated at a corner table with three friends. Her name is Beatriz García Paesa.

García Paesa left Spain in the early 1990s with her brother and uncle after the courts accused them of being involved in laundering the millions of euros stolen by disgraced former Civil Guard chief Luis Roldán.

García Paesa is the niece of Francisco Paesa, a convicted fraudster who served time in a Swiss prison in the 1980s before becoming Spanish Interior Ministry fixer. He has been involved in nefarious activities - official and extra-official - dating back to the late 1960s, and is now in hiding in Luxembourg after being accused of stealing 10 million dollars from Russian magnate Alexandr Lebedev.

García Paesa's niece, Beatriz, runs a small law firm in the tax haven with offices on the nearby Boulevard Royal. Few Spaniards in the city are aware of her family connections.

Friends and acquaintances say that Francisco Paesa showed an initiative for unorthodox business dealings and taking risks early on. He quit his studies at a private college when he was 22. A decade later in 1969, after marrying into a wealthy French family, he persuaded the then president of the former Spanish colony of Equatorial Guinea, Francisco Macías, to make him president of the West African country's national bank. Paesa was supposed to arrange for funding, but the money never arrived. Francisco González, head of BBVA bank, says that he "saved his life. Macías wanted to hang him."

In the 1970s, Paesa set up the small Geneva-based Alpha Bank. "He's always been interested in finance," says a former friend from the Spaniard's student days. "After he set up Alpha Bank, if you wanted to divert money to Switzerland, you went to see him. He had a reputation for being honest: he would keep a small percentage, and transfer the rest of the money," he adds.

Another former school friend remembers Paesa less fondly: "He was very smart, and had no morals. He stole three friends' watches when he was 14, and was kicked out of school. He was always a show off; he loved cars, women, and good suits. He was the first to smoke Chesterfield at school."

Alpha Bank's illegal activities were uncovered by the Swiss authorities. Paesa was imprisoned for 18 months and then banned from Swiss territory.

It was at this point that he decided to work for the Spanish security services. He was involved in a successful police operation to sell missiles to ETA that had been fitted with radio transmitters, which led to the break up of a cooperative set up by ETA to launder money extorted from Basque businesses. This success led to him becoming a middleman for the Socialist Party government of Felipe González and the so-called Anti-Terrorist Liberation Group (GAL), secretly set up and funded by the Interior Ministry to wage a dirty war against suspected ETA members in France during the 1980s.

The GAL used mercenaries to kill 26 people in a series of botched operations - furthermore, most of those killed had no direct involvement in ETA. Paesa was accused of making payments to mercenaries, as well as attempting to buy the testimony of two women who were the girlfriends of Spanish police officers arrested for their involvement in the case.

Paesa fled Spain, obtaining a diplomatic passport from Santo Tomé and took up residence in Switzerland. Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón issued a warrant for his arrest, prompting the Swiss authorities to expel him again. He gave himself up to the Spanish police and was questioned by a judge in 1991 but was not prosecuted for lack of evidence.

Three years later, it was discovered that Luis Roldán had been charging construction companies commissions to build Civil Guard barracks. Knowing of his contacts and seeming immunity to justice, Roldán enlisted Paesa's help in laundering the 10 million euros that he had accumulated, and then in helping him to flee to Laos.

Paesa then sold his services to the Spanish police, persuading Roldán to give himself up in Bangkok a year later. Media reports at the time said that he was paid more than a million euros for turning Roldán in.

Three years later, Paesa's death notice was published in EL PAÍS. He was alleged to have died from a heart attack in Thailand, where his body was supposedly cremated. The authenticity of the notice came into question when no family members attended the funeral mass, which was held at a monastery near Burgos. Shortly before the death notice, around five million euros were removed from Paesa's bank account.

In 2004, media reports had Paesa living in Luxembourg under a new identity, and with an Argentinean passport. Shortly after, a Spanish court ruled that under the statute of limitations, he could no longer be pursued for the money-laundering charges.

But Paesa, it seems, is unable to kick back and enjoy his ill-gotten gains. On October 6, the 75-year-old was arrested by the authorities in Sierra Leone and held there for three days.

According to the Cadena Ser radio network, Paesa, travelling with his nephew Alfonso aboard a light aircraft chartered in Sierra Leone, told police in the West African state that he was representing a French lawyer and was there to verify a cargo of antiques, including old perfume bottles and Chinese golden masks. When the pair were arrested, they were both in possession of valid Spanish passports in their own names.

The authorities in Sierra Leone refused to believe him, suspecting that he was involved in drug smuggling, so Paesa contacted the Spanish Foreign Ministry, which obligingly flew him out of the country to France, where he was released. Cadena Ser cited sources at the Foreign Ministry as saying they believed that he was involved in a major gold transaction. In a report, the ministry said that it had not questioned a man who for years was on Interpol's most-wanted list because there were no charges against him in Spain.

Having used his contacts in the higher echelons of power in Spain to get out of that scrape, Paesa now finds himself facing investigation by the Luxembourg authorities. The Appeal Court of the Gran Duchy last week confirmed a decision by investigating magistrate Stephane Maas to investigate Paesa and his niece over the disappearance of 10 million dollars belonging to Russian magnate Alexandr Lebedev. At the end of the summer, Luxembourg police searched Beatriz García Paesa's offices. The case is now sub judice.

Luxembourg is renowned for its no-questions-asked approach to banking. And sitting in the Confiserie Namur earlier this month there were likely any number of fiduciaries whose names feature on secret accounts and investment funds. Luxembourg's 500,000 inhabitants have the third-highest per capita GDP in the world, while dozens of banks and lawyers are located throughout its 2,500-square kilometers bordering France, Germany, and Belgium. Its government has consistently refused to provide information about possible fraud and tax evasion to the EU.

"This is the last chance to catch Paesa and make him pay for what he has done. He has always managed to walk away, because he is protected by the secret service," says a member of the Luxembourg judiciary in confidence.

García Paesa gets up from her corner table and makes her way through the tables to the elegant staircase. Asked by this journalist if she would mind joining him at his table for a few moments she agrees, although her companions across the room look uncomfortable.

"I have nothing to do with the Lebedev case. I have not been charged or questioned. My office was broken into and documents were taken. They are looking for my uncle, so they should find him and ask him. These Russians are trying to use me against him. The charges they tried to bring in a Bahrain court have been refused. Why don't you ask them where the money is?"

I reply that she and her uncle are now under investigation by the Luxembourg authorities for alleged falsification of documents related to the Lebedev case.

"I don't know anything about that. I don't know anything about my uncle's affairs. Our business affairs are limited to family matters," she replies.

I ask her about the money that Luis Roldán stole, and which has never been recovered, pointing out that both her brother and uncle have both been accused of laundering it. Swiss judge Paul Perraudin described her and her brother as "collaborators and fronts for their uncle."

"I have never been contacted by the police or the courts over that matter. I have been living here for years. I am not hiding. If they haven't contacted me it is because they do not want to. I am a tax lawyer and just want to get on with my work. All this is very damaging for me," she says.

One of the men from her table comes over with a mobile phone and takes several photographs, slowly moving round the table, taking his time to get profile, three quarters, and full frontal shots, and making no effort to hide this from the Namur's genteel cake eaters.

Asked about the need for the photographs, she replies: "I have to take precautions."

I continue with the questions, asking if she knows two lawyers called Jean Paul and Monique Goerens, who opened a bank account in Singapore that was used to deposit Roldán's still-missing stolen 10 million euros.

"I know them, but I have nothing to do with that," she answers.

Asked about the death notice placed in EL PAÍS in 1998 announcing her uncle's death in Thailand, she says simply that she was "notified" that he had died.

She also says that she had nothing to do with her uncle's trip to Sierra Leone. The tipping point is when I point out that her brother has several companies registered at her offices.

García Paesa gets up, and says that she is ending the conversation for now, but that she will talk later by telephone about the Lebedev case. The discussion never takes place.

Alexandr Lebedev, a former KGB agent, banker, politician and the owner of British dailies The Independent and the Evening Standard, and worth around 2 billion dollars, according to Forbes magazine, says that he entrusted Paesa with some 20 million euros to set up a bank in Gulf state Bahrain, but that half of the money has disappeared in a complex network of accounts and front companies, while no bank has yet been set up.

Four million euros supposedly stolen from Lebedev were sent to an account in the Overseas Union Bank of Singapore, the same bank that Paesa used to hide the millions stolen by the former Civil Guard boss, to be used for an investment project in China. Lebedev's money has subsequently been transferred to dozens of other accounts, using the same paper trail method Paesa employed to make Roldán's money disappear.

A colleague says that Lebedev is less interested in the money and more concerned about "honor." Lebedev says that he met Paesa through a former employee. "He was recommended by foreign lawyers. I met him in Paris. We had tea. He said that Bahrain was emerging as a leading offshore financial center, with transparent legislation, and that he had contacts there. He introduced himself as Francisco Sánchez, a Paris-based 'financial expert' with an Argentine passport.

"There was something not quite right about him. I thought that he was probably dishonest, but my team decided to work with him. I don't understand how he was able to trick us. The whole thing was a scam from beginning to end. I don't think he even bothered to make an application to open a bank in Bahrain. He just stole the money as soon as it arrived there."

When it was discovered that the 20 million euros had disappeared and that Sánchez was in reality Francisco Paesa, a team of lawyers and detectives set off on the trail; a trail that so far has led nowhere. "There is nothing in his name: his house, his car, his accounts. When the money disappeared, he moved apartment and rented somewhere on the Champs Elysees. He moved around with his furniture and his paintings from one place to another trying to cover his tracks," says a source who met him during that period.

"Don't worry, the money will reappear," Paesa reportedly told Lebedev's envoys. He then threatened to spread rumors that Lebedev was linked to the Russian mafia and that he was being threatened. "He is protected by the European secret services. The French secret service doesn't protect him, he protects France," says Lebedev.

Paesa has few links with Spain now. His secretary for many years in Madrid died earlier this year after a long illness, and Paesa didn't attend her funeral. She told me repeatedly over the last two years that she expected to see Paesa, but he never turned up.

Neither did he attend the funeral of his mother. His ex-wife, who lives in France with his daughter, says that he has broken contact with them. His nephew and niece, Alfonso and Beatriz, are the only people known to be in contact with him.

"His secretary had a phone number to contact him, but never revealed it. I haven't heard from him for years," says Manuel Cobo del Rosal, his lawyer in Spain.

When I called Beatriz García back that afternoon in Luxembourg, she told me that she was in her office with several lawyers and that our conversation was being recorded. "I have nothing to say. I have nothing to do with the accusations against my uncle. If you publish my name then I warn you that I have the right to take legal action against you," she said.

Though Paesa's niece describes herself as an expert on international tax law and intellectual property rights, "she is not known in the courts," says a leading lawyer in the Grand Duchy.

At Christmas, Beatriz attends the Spanish stand at the international charity fundraiser. Her name features on a long list of companies based in Spain and Luxembourg. She is a member of the board of Alcudia Cartera de Inversiones, an investment fund set up by the March bank. The bank says that the fund was checked for money laundering.

"Garcia Paesa is the fund's representative in Luxembourg. We did not know who she was," said a spokesman.

Alcudia Cartera de Inversiones is headed by Hugo Aramburu, who runs Banca March's private banking arm. It was set up to buy 1,000 offices that BBVA put up for sale, and has current assets worth 58 million euros and a capital base of 10 million euros. Asked who Beatriz García represents within the fund, the bank said it was not at liberty to say.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.