I will not forget you

Despite ETA's announced break with violence, victims still have to come to terms with the past and the possibility of atonement

That morning, her husband told her: "Last night I dreamt that they were killing me." Maixabel didn't know what to say. When the doorbell rang a few hours later, she knew that something had happened. And she was right. Juan Mari Jáuregui, the former civil governor of Gipuzkoa, had been shot twice in the back in a café in Tolosa. He died hours later, on July 29, 2000.

Luis Jaime Palate was at home, in a small Andean village called San Luis de Picaihua, when he learned that his brother Carlos Alonso had disappeared. He was found days after the explosion in the parking lot of Barajas airport on December 30, 2006 that broke the truce that ETA had announced nine months earlier. That was the first time he had ever heard of the terrorist group.

None will ever forget the moment that ETA changed their lives forever

"Since then, every attack has been like reliving my brother's death"

Josu was working in Ataún when he got the call: "There's been a terrorist attack in Lasarte." He phoned his mother, but no one answered. Then he tried one of his friends: "It's your father," he heard on the other end of the line. On his way to Lasarte, 40 kilometers from Ataún, he heard it on the radio. Froilán Elespe, his father, had been killed. He was the first Socialist councilor to be assassinated by ETA, on March 20, 2001.

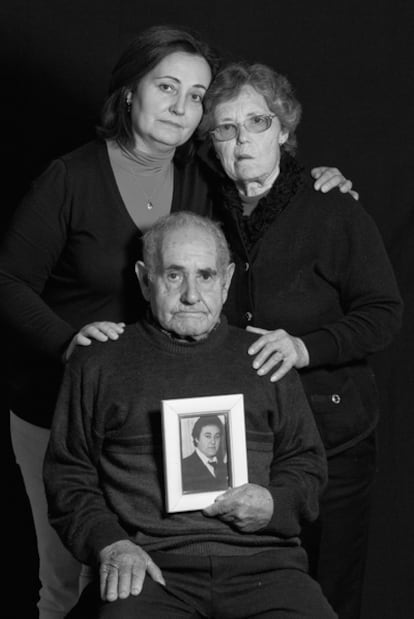

Hortensia was watching TV when she recognized the enormous shoe of her son Alberto, a 23-year-old Civil Guard officer who wore a size 47, from among the bloody images of the attack on April 25, 1986 in Madrid. She's been told that she tried to jump off the balcony after seeing it, but she doesn't even remember that moment.

Lourdes didn't need a radio or a TV to find out. She was just behind her husband, army officer Luis Conde, when a car exploded, killing him. They were in the process of evacuating a military building in Santoña, in the Cantabria region, after receiving a bomb threat on September 22, 2008.

None of them will ever forget the moment that ETA changed their lives forever, especially now. The group's October announcement of a "definitive" end to terrorist attacks has stirred up painful memories for these families and many others who now face the possibility of a future without violence.

"I have a really hard time believing it, but I hope it's true," says Yolanda, the sister of Juan García Jiménez, who was the chauffer for Colonel Vicente Romero. Notorious ETA hitman Iñaki de Juana Chaos gunned both of them down the day that Spain joined the European Economic Community (now the EU) on June 12, 1985. Juan was shot seven times. At the time, Yolanda was living in a tiny village in the province of Ciudad Real, Retuerta del Bullaque. Someone called the only phone in town to tell her the news, and she had to seek out a neighbor with a car to drive her to Madrid.

"Since then, every attack has been like reliving my brother's death," she says, 26 years later. "You know what the family is going through because you've gone through it; because you're going through it. Time helps you live with that pain, but the wound never heals. That's why I really hope that this never, ever happens again. No one can understand that better than us."

Hortensia Gómez, mother of civil guard Alberto Alonso, echoes this sentiment: "Please, don't say that we don't want peace. Of course we do, and as soon as possible. All I ask is that we don't start acting as if those crimes hadn't been committed."

There are 829 deaths on the table, according to Interior Ministry figures. Of these, 486 were members of the armed forces or the state security forces - primarily Civil Guard officers, and national and military police - and 343 civilians.

The total goes up to 851 if you count the assassinations carried out by the Autonomous Anticapitalist Commandos and others that the government considers to be related to the terrorist organization, even though strictly speaking, ETA did not carry them out. For instance, there is 79-year-old Ambrosio Fernández Recio, who was asleep in his bed when a group of young people threw incendiary bombs at a bank in Mondragón (Gipuzkoa), on January 6, 2007. He was evacuated, along with all the other residents of the building, inhaled a lot of smoke and forced out into the cold. Days later, he was admitted to the ICU of a hospital, where he died on March 3. The government has indemnified his relatives as victims of terrorism after a doctor certified that what happened that night caused the man's health to worsen, leading to his death.

But what about the survivors of ETA attacks? They include numerous police and civil guards stationed in the Basque Country who watched their colleagues die. "In the 1980s, ETA killed us like dogs," says retired national policeman Ángel Chaparro, a native of Melilla, who was stationed in Bizkaia from 1974 to 1987. "Politicians didn't pay much attention to the victims until they started getting killed themselves."

He is only alive because he saw a strange bag underneath his car. If he had moved the vehicle, he would have been blown to bits. He has just been recognized as a victim of terrorism. "Since nothing happened to me, it's no big deal to them. My wife and daughter watched the controlled explosion of the car and had panic attacks. My life has never been the same since."

Civil Guard officer Antonio Álvarez Zafra, from Jaén, was shot three times at the barracks in Salvatierra (Álava). He ended up with a broken femur, permanent leave for incapacity and deep psychological scars.

If it's true that there are going to be no more attacks, the question is: now what? How should the end of ETA be handled, considering all the pain and suffering endured by the families of the over 800 people killed and the thousands injured, threatened, blackmailed or forced into exile by this terrorist group? They are regularly referred to as "the victims" of ETA, but it is not a homogenous group. "We're as diverse as society itself," says Josu Elespe. "Unfortunately, ETA has done so much killing that there are too many of us for everyone to think and feel alike."

It's not the same to have lost a relative in the 1980s (when the widows of terrorist attack victims, who barely got a mention in the newspapers, were forced to bury their loved ones and leave the Basque Country almost in secret)as to have lost one in 2008, when there was already total consensus about the brutality of the organization and each funeral was a state affair. It's not the same to lose an elderly father, no matter how painful or unfair this may be, as to lose a son who is just starting to live, like Juana and Juan, the parents of Juan García Jiménez. Stuck in a day from 26 years ago, they are hardly even able to leave their home. And it's not the same to live in Málaga as to live in a town in Gipuzkoa, forced to see pro-ETA graffiti and posters on a daily basis.

There are victims that have received a lot of media coverage and social support, and others who have been totally alone. Some of them have joined one of the victims' associations; others have not. Some have overcome the suffering; others never will. And the most recent victims are still in the middle of the healing process, struggling to cope with the fact that if peace had come just a little bit sooner, their loved one would still be alive.

"Recently, my 10-year-old nephew was asked at school if he knew what a truce was," says Lourdes Rodao, the widow of Luis Conde, killed in 2008. "He said that for him, it meant that if there had been one three years ago, his uncle would still be here. I can't get those words out of my head."

For the newly widowed such as Lourdes, it's hard to accept the ceasefire, which they receive with a mixture of skepticism, joy and profound sorrow that it didn't come just a little bit sooner. "On the one hand, I was glad," says Lourdes, "but it's also made me fall into a slump again, when I was still recovering."

Depending on the intensity of the suffering, reactions differ. Parents who have lost a child, for example, have a very hard time believing anything that ETA says. In general, they are not willing to let go of their loss, although there are some exceptions. Most of them would appreciate, in any case, to hear the terrorist group admit that it has caused immeasurable pain and suffering and that killing to defend political ideas that should only be defended with words was a mistake. It would be a big, reassuring change from the arrogant attitude that they've had to deal with until now. Yet there are also those who think that any step in this direction would be merely strategic, not sincere.

"How am I supposed to forgive the fact that they didn't let my baby live?" says Hortensia Gómez. "I can't. They destroyed my life, my husband's life, and the lives of my children. We've never gotten over it. But asking for forgiveness would be a gesture. I'm about to turn 70; I've suffered so much, and I think that I deserve that."

"I decided to forgive from the beginning, perhaps for religious reasons, and for myself," says Pedro Mari Baglietto, the sister of Ramón Baglietto, a member of Azkoitia town council assassinated by ETA in 1980. For Iñaki García Arrizabalaga, whose father was killed by the Autonomous Anticapitalist Commandos that same year when he was just 19 years old, forgiveness wasn't automatic. "At first I felt a great deal of hate," he says. "Little by little, I realized that I had to let go of that hate so I could keep on living. They had already taken my father's life; I wasn't willing to let them take mine away from me, too."

To date, Iñaki is the only person who has spoken in public about the face-to-face meetings between ETA dissidents at the Nanclares de Oca prison and victims of the organization. Some of them, a minority, have sat down with a member of the cell that murdered their relative. In other cases, like that of Iñaki, where those responsible were never apprehended, the relatives have met with an ETA prisoner not directly related to the attack that killed their loved one.

Few victims go down this route for two reasons: most of the prisoners aren't willing to deal with the pain that they've caused, and most of the victims haven't wanted to meet them, either. Iñaki defends his choice. "For me, it's been an extremely valuable human experience; the person who I saw didn't receive any penitentiary benefits for doing it; I think it was sincere, and for me it's been like my own little contribution to healing this society's wounds. Of course, I totally respect those who don't want to do it."

The official group of ETA prisoners, in its latest internal document, gives very clear instructions: no remorse, no forgiveness. Meanwhile, the nationalist left is trying to figure out how to acknowledge the pain it has caused, aware that it must make some reference to the victims as a necessary part of its roadmap to peace. At any rate, it's going to be a long, drawn-out process, with slow steps that are unlikely to satisfy the victims. Like the step taken earlier this month by the nationalist political parties who signed the Gernika Agreement, which merely expressed its "regret" about the victims of "ETA violence," as well as the "repressive strategies and dirty war carried out by the Spanish and French governments."

"Forgiveness is a very difficult thing," says Enrique Echeburúa, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of the Basque Country. "Due to the emotional subjectivity that it entails, it's got to be real. If it's not genuine, it can be disastrous [...] If the terrorists admit that they did wrong, it would help heal wounds. But there are other things that they can do. For example, making sure there are no tributes to terrorists. These are unnecessary affronts that hinder the healing process."

Aside from forgiveness, recognition of the damage done or self-criticism about past crimes, the end of violence is going to require concrete decisions by Spain's new conservative government: whether or not to transfer ETA prisoners back to the Basque Country, how flexible it is going to be about penitentiary policy, and what the essential requirements for ETA prisoners to get penitentiary privileges are going to be.

The law is flexible, which means it can be applied in various ways. When it comes to bringing the prisoners home, for example, the government has free reign to do what it thinks best. Some of the victims don't even want to hear about it, at least until ETA hands over its weapons. Juan García Jiménez's family falls into this category. "They talk about the suffering of relatives of the prisoners, but we go to the cemetery and all we see is a slab of stone," says Yolanda, Juan's only sister. "No matter how far we go, we'll never see him again."

Josu Elespe, however, doesn't mind if they make penitentiary policy more flexible. "But the perpetrators of crimes should be tried, and if there's evidence, put in jail." For the assassination of his father, two ETA members have been arrested in France and one in Spain. "I want to go to court. For a feeling of justice with a capital J and for personal reasons, to get closure. I'm confident that, no matter what happens from here on out, the law will be applied and they will be brought to justice, without taking the current situation into account."

If all the victims agree on one thing, it is this: they don't want to see the government ease up on arrests, or see the murderers walk. It's one of the few shared demands of a group that is proud to say that not a single one of its members has ever taken justice into his or her own hands. There have not been any personal vendettas during the long years of terrorism. They also agree on rejecting any illegal action carried out by the state in the fight against terrorism. In return, they demand justice.

Then there is the question of memory. This is something that the victims who live in the Basque Country are particularly concerned about. The rest are confident that the history books will say that a terrorist group killed, threatened and blackmailed innocent people for decades. In the Basque Country, it's not so clear that this is going to be the case. The alternative version is that there was a war, and everyone suffered. That's why the victims there are determined to make sure that their stories aren't forgotten, to keep the record straight.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.