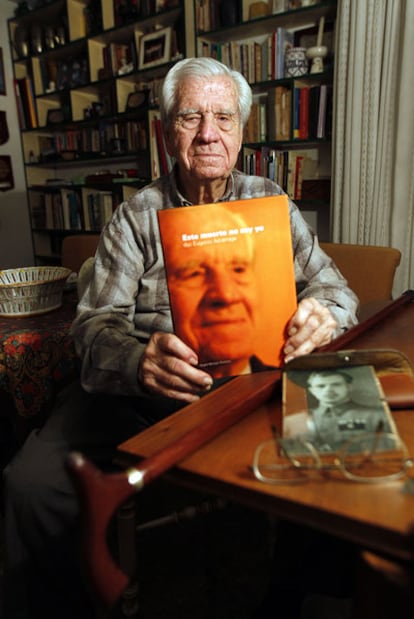

"I am buried in Franco's tomb"

Veteran explains why his name is engraved at Valley of the Fallen

"I am buried at Valle de los Caídos, registration number 8,273, columbarium 1,718," says a 95-year-old man who is very much alive and has just got back to his house in Valencia after spending the day out at sea, his great passion. His name is Eugenio Azcárraga and his name is indeed on the burial book kept by the Benedictine monks at this giant mausoleum north of Madrid, built for Francisco Franco and containing around 34,000 bodies of combatants from both sides of the Civil War (1936-1939). A commission appointed by the outgoing Socialist government last week recommended that Franco's remains be removed from the Valley of the Fallen so that the monument can become a symbol of reconciliation.

According to the records, Azcárraga fell at the Battle of Teruel and was buried here. He discovered the mistake years ago, during his one and only visit to the monument - which includes a rock-hewn basilica and a 150-meter tall cross - and he never bothered to have it corrected. But the mix-up is the result of a complicated story that begins in 1936 and saw Azcárraga nearly die on several occasions - and those times for real.

"I was 20 years old when the Civil War broke out, and I had no political ideals," he recalls. "Back then, swimming is what interested me - I was the 400-meter champion in my city. That, and girls. We lived in Valencia and the Republicans killed two cousins of mine, a 20-year-old boy and a 19-year-old girl, because they were the children of a marquis; because they were rich. So I decided to go over to the Nationalist side. If I'd been asked: 'Would you rather be a red, a Francoist or be left alone?' I would have surely said be left alone. My family was rather liberal," says a man whose grandfather was Marcelo Azcárraga, a prime minister under the regency of María Cristina, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Since he'd spent several months on the front lines in Asturias and had studied some law, Azcárraga was provisionally made second lieutenant and stationed in Villaespesa, Teruel. "To me, the worst memories of the war are from Teruel, in the basement of the seminary where the civilian population had taken refuge. I had seen dead bodies in Asturias, but they'd been wearing khaki uniforms. In that basement, there were broken bodies of women in pink coats. And dehydrated children, because there was no food or water or anything down there. The wounds of the living were dressed with bandages taken from the dead. I was in the trenches and I only went down there twice, but I would rather be in the riskiest spot of all than to have to see that."

It was in Teruel that the whole mix-up surrounding his death had its origins. "There was a Navarrese official who looked like me, tall and blond. And I suppose that's where the whole confusion began..."

Eugenio Azcárraga had just received a letter from a Navarrese "war godmother," a name given to women on the Nationalist side who volunteered to send messages of optimism and small gifts to soldiers on the front, as a way to maintain troop morale.

"But I was not interested in Navarre, because if they gave me leave, I wanted to go to San Sebastián, so I wanted a Basque war godmother. And so I gave my letter to my colleague from Navarre," he continues.

Eugenio does not know whether officials got him mixed up with that other second lieutenant who looked like him and had a letter addressed to him on his person, but the fact is, he was given up for dead. "When the Nationalists entered Teruel again, they dug up the bodies that remained there after the battle to identify them, and took them away. I was theoretically among them. My mother received a telegram informing her of my death, and there was even a funeral for me in San Sebastián. But I wasn't dead. I was a prisoner at that time."

With the fall of Teruel, Eugenio Azcárraga was held prisoner by the Republicans, who took him and others to the castle of Montjuïc, in Barcelona. "I spent a long year there, starving to death, and I remember how we used to joke about how many chick peas we'd each received. And when the Nationalists were going to free Barcelona, our captors stuffed us into a train, I think not knowing very well where they meant to take us. I jumped off the moving train with 15 other prisoners. One died on the spot. The rest of us fell on a meter-high snow drift. The Republicans realized what had happened and started to chase us, but they just fired a couple of shots in the air, and considering how cold it was, probably thought: screw them. So we started crossing the Pyrenees on foot. It took us all night. One fell along the way; he couldn't go any further. Of the 15 who jumped off the train, 13 of us made it to France."

They took another train back to Irún, a Basque border town under Nationalist control, and Eugenio was reunited with his family. "My mother had been in mourning at first, but then an uncle found out that I was a prisoner at Montjuïc, so she wasn't surprised that I wasn't dead. She had a strong sense of humor, my mother, and we joked about this a lot."

"One day, the mayor of Teruel told me there was a gravestone with my name, and indeed there it was: Eugenio Azcárraga Vela, fallen for God and Spain. It's true I could have fixed the error, but I was very young and I didn't stop to think about such things. My mother told me to do something about it, because she didn't want people to walk by and see the gravestone with no flowers and have people think nobody loved me. But I went to see the priest and he said to wait, so for years I played jokes on my friends and took them to see the most important monument in Teruel: my grave. And then one day it wasn't there anymore, and the undertaker said the remains of unclaimed people had been taken to Valle de los Caídos."

Eugenio went there a few years later and there was his name. "I didn't tell anyone about it. Now I would be more interested, but back then I was still more interested in women than politics."

Despite being on the record as dead, Azcárraga kept his official ID and never had any trouble. After the war, he stayed in the army for a while and served in Africa with a cavalry regiment. But an uncle convinced him the army did not pay well and that once he married it would be difficult to move his family around, so he quit. He started working for an export company that made fireproof material, and says he did quite well for himself.

"I've been on all five continents and in very odd places, like Iran, Iraq, Cape Town, Brunei..." But he never returned to Valle de los Caídos. Azcárraga thinks the idea of exhuming Franco's remains is "nonsense" and that "it makes no sense to argue over such a painful past as the Civil War. I'd leave things the way they are. All civil wars are absurd, and so was ours. Depending where you were, you fell on one combatant side or the other and you had such absurd situations as two brothers fighting each other or a Galician man shooting a gun in Teruel. We were killing one another. We have to forget. I fought on Franco's side, yet I think that Franco got it 100 percent wrong with his subsequent repression. After winning, to kill so many people has always seemed a brutality to me. But I like to talk to my grandchildren about swimming and sailing... not about my war stories."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.