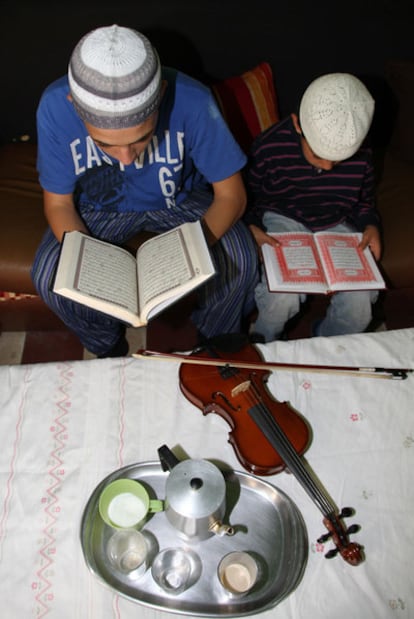

"Music is the horn of Satan"

An extreme Salafist group is taking root in the Spanish enclave of Melilla. Their customs, such as a rejection of songs and instruments, are beginning to show up in schools

The 30 kids in one of the freshman classes at Rusadir Secondary School, in Melilla, lift up their flutes and start playing a tune. The instruments of Suleiman and her cousin Abdelkrim (not their real names), both of them 12 years old, sit on their desks, inside their cases. When the school year began, the two boys refused first to bring the instrument to class, and then to play it, either offering excuses or dodging the issue altogether. Lamia, aged 14, Suleiman's sister and a third-year student at the same school, doesn't want to study music either. All three are Spanish nationals.

"Suleiman, why won't you play?" asks the teacher yet again.

"I don't want to play the flute; I don't want to study music."

"Why not?"

"I don't know... I just don't want to."

"Music is a mandatory subject; you can't choose what to study and what not to study. Go get your backpack and get out of class!"

None of the three kids dares to tell the teacher the real reason why they don't want to study music. Their whole lives, they've been told the same thing: "Music is the horn of Satan," the supreme incarnation of evil.

Suleiman, Abdelkrim and Lamia (not her real name, either) are afraid that the sound of the flutes will make them sin. Just like in Afghanistan, during the Taliban regime, or in Somalia, where a year ago Moallim Hashi Mohamed Farah, the man in charge of Mogadishu for the Islamist faction Al Shabab, a loyal ally of Al Qaeda, gave local radio stations 10 days to stop airing music.

Salafism is on the rise here on the North African coast in Melilla and its most extreme customs are making their way into public school classrooms. It is the sign of a growing minority made up of bearded cab drivers, women who wear burqas and niqabs, and radical mosques where they preach that singing, dancing, going to the theater or the movies and watching television are all sins. "Next thing you know, they'll say soccer is prohibited," says Fátima, a 25-year-old woman who lives in Cañada de Hidum, the poorest area of town.

Rusadir Middle & High School has 1,000 students, almost all of them Muslim. Built a decade ago in the Tiro Nacional neighborhood, it has the highest academic failure rate in town and one of the highest in Spain. "Of the 200 students who start middle school, only 30 get their diploma. Almost half of them have illiterate parents," according to the school principal, Miguel Ángel López Díaz. Suleiman and Abdelkrim, the cousins who refuse to study music, are both good students.

Suleiman has huge black eyes, a round face, short hair and a sweet, trusting look about him. He is wearing a navy blue jogging suit, a white t-shirt and trainers. In Melilla, they're celebrating Eid al-Adha, the Festival of Sacrifice, and she didn't go to class. "How did you get my address?" she asks in the presence of Azzid, her father, a 46-year-old Moroccan who has been living in Spain for 21 years and is leaning on his van, which is parked in front of their home.

The kid gives one-word answers at first, before he finally opens up. "Music is bad and useless. Last year I also refused to study and they didn't say anything. They gave me an unsatisfactory grade and that was it. This year they've started with the punishments. I've been punished three times. They say, 'Get your backpack and leave.' One day, I was punished for several hours and missed a lot of classes."

"Why is music bad? Explain it to me."

"I know that it's bad. I know that it will hurt me... my head, my thoughts. I've known this since I was a child. There is another kid [his cousin] who doesn't want to study it either."

"Why don't you just do it so you don't get punished?"

"I don't want to think about it. I don't want to feel any temptation. I'll never study music, even if I have to drop out of school. I go to class, but I don't do anything. I don't listen, I don't learn, I don't participate. I try to think about something else. I try not to hear it."

Azzid, his father, has a long beard and wears a dark djellaba and ankle-length trousers. These are a sign that he considers himself to be a pure, authentic Muslim, something that can be seen more and more these days on the streets and in some mosques of Melilla. He lived and worked in Barcelona for 15 years, where his two children were born. Six years ago, he moved to this city of 71,000 people, half of them Muslims, to be closer to his Moroccan family. Azzid avoids explaining what music means to him, but he gives his opinion, in perfect Spanish, of what his son thinks.

"Did you tell the boy that music is a sin?"

"He's got very strong convictions and firm ideas. He's known what he wanted ever since he was young. They say that there is religious freedom here, but that's not true because then they make you study things that go against your religion. Isn't that a contradiction?"

"Music is a required subject."

"I know it is, but you've seen that he doesn't want to study it and I'm not going to make him. Let them change the law and give him the freedom to study it or not."

"Isn't the boy just doing what his parents tell him to do?"

"It's up to him. The girl, my other daughter, feels the same: she doesn't want to study music either."

Azzid says that his son is not going to give in and says that he plans to pull them out of school. "They're breaking his heart, and if they don't let him keep studying here, I'm going to take him to some other country. He's a good student, one of the best in his class. I told the principal to put in writing the reason for kicking him out and I'll take him somewhere else. The last time I picked him up after being punished, he was yellow. They're harassing him with the punishments. He's losing the tranquility that a boy should have. Why don't they respect the way he thinks and lives? I'm afraid that this will affect him and ruin his education. And who will be responsible?"

"You don't feel responsible?"

"No."

"How did you find out where we live?" Suleiman asks again before walking through the door of his home, near Melilla's central mosque.

The family of his cousin Abdelkrim lives a 10-mintue walk away. Their building is closed for the Festival of Sacrifice, and the streets are empty. Most of the residents have crossed the border to visit their families in Morocco. Several weeks ago, Abdelkrim's mother went to the entrance of Rusadir School in her black burqa, but they wouldn't let her in. The principal had called the parents of both boys to inform them about their refusal to study music.

This is how Miguel Ángel López, the principal, remembers it: "The music teacher told me that two kids were refusing to study music. They wouldn't bring in their flutes, they wouldn't do their homework, they wouldn't play. When one boy's mother came, we didn't let her in. I can't talk to a woman if I can't see her face. Entering the school like that is not permitted. The boy's 20-year-old sister came in instead and we told her that here, students don't get to choose what they study, and that music is a required subject. We tried to convince her that musical language is necessary, that it's a form of expression. Without coming out and saying it, she admitted that it was a religious matter, and that their family was very orthodox. She said that she'd talk to her parents."

Abdelkrim brought his flute in the next day and went to class. "He put it on the desk, but he didn't want to touch it. They think that music is a sin - that's the problem, even though the kids won't admit it. What are we supposed to do with a boy who refuses to study a certain subject? It's the first time we've ever had a case like this," says the principal.

López had a similar conversation with Azzid, Suleiman's father, who insisted that it was the boy's decision: "'You can see that he doesn't want to; what am I supposed to do about it?' the boy's father told me in front of his son. I'm afraid that this will spread and affect other kids." The principal of Rusadir has sent a report on the matter to the directorate of education.

Abdelila, 44, originally from Nador (Morocco), is the imam of the "white mosque" in Cañada de Hidum, the strictest religious temple where many of the bearded worshippers go. Abdelila has been living there for 11 years, but he doesn't speak Spanish, just like most of the 12 Moroccan imams that lead prayer in the city's mosques. Earlier this month, on the Festival of Sacrifice, his congregation prayed in a parking lot near the mosque. They didn't go to the big gathering of more than 5,000 Muslims who went up next to the Foreign Legion barracks to pray. They don't want to associate with them. The imam, clad in a golden tunic, is resting on a mat before mid-afternoon prayer begins. "If you listen to music and it touches your heart, the words of the Koran won't reach you. In Islam, music is sinful. It's written in the Koran. Music goes against its teachings and leads you down the wrong path," he says.

"What if the lyrics are about peace and love?"

"The message doesn't matter; the lyrics don't matter. Don't you see that it's a big sin? We can't listen to it; no Muslim should hear it. How are we going to let our children be corrupted by it?"

One of Abdelila's children enters the room adjacent to the mosque and the imam admits that the boy doesn't listen to music, "except when he watches certain cartoons." "For the faithful, it's very easy. There are many 14- and 15-year-old boys who are very firm believers. There are lots of people who think the way we do; we're not a minority."

Mohamed, a 34-year-old fumigator and a regular at the mosque, adds: "I haven't listened to it for four years now. It's no good for good Muslims."

At 4.20pm, around 30 bearded men, all of them wearing tunics and ankle-length trousers, come in to pray. Built in 2005, this mosque is painted in white and appears in many of the reports drawn up by the police and the National Intelligence Center (CNI). Its leaders deny any kind of connection with Salafism, one of the most radical strains of Islam.

Cañada de Hidum has the highest unemployment and academic failure rates in this Spanish enclave, on the north coast of Africa. During the recent municipal elections, groups of young people burned dumpsters in protest after the conservative Popular Party won 15 out of 21 seats. With Juan José Imbroda as leader of Melilla, they said that employment plans would "never" reach the neighborhood. Our date with the "strangers" takes place on the road to this neighborhood, the poorest in town. It is dusk, and Mustafá, 40, one of the promoters of the "white mosque," is chatting with his friends under the stars. Sitting on folding chairs clad in dark tunics, they proudly show off their ankles and long beards. All of them have covered their heads with wool or knit caps. It looks like something you might see in a place like Pakistan or Afghanistan. They know they look strange to others, but they flaunt their difference. "Write this down. Islam started out as something strange, and it will again become strange as it started out. Blessed by the strangers, those who remained steady while the rest degenerate," says Mustafá.

They are the ones who have remained "steady;" the rest, the 5,000 Muslims who went up to pray next to the Legion barracks earlier this month, are the ones who are supposedly degenerating. "They claim to be Muslims, but they're not. Very few people know what Islam is, in its pure essence. They use it for their worldly and material interests. They seem to be one thing, but they're really something else. Our relationship with them is that of indifference. They make us out to be radicals and extremists. But who are the terrorists? The ones that attack a country with bombs, kill children and women, or the ones who defend their home? They switch around the names of things."

Mustafá is the only one who talks: the others just listen. They're all married and have young children. None of them will listen to a song or sing one. Not even at school. "How are they going to study music if the Koran prohibits it? They say that if you don't study it, you'll flunk the course. It's like living in a huge prison, like the walls that go around this city. Music is for beasts, music is the horn of Satan." Osama bin Laden, the leader of Al Qaeda killed months ago in Abottabad (Pakistan), defined music with a similar sentence: "Music is the flute of the devil."

"Why do think it's so bad?"

"Because it makes people do illicit things, because it distracts and corrupts."

Mohamed, a man in a bright blue djellaba, is the only one who dares to add something to what his friend has to say. "There are other problems besides music; the school won't let you wear a headscarf either. For us the headscarf is the niqab [the garment that covers the entire body, with only a slit for the eyes]."

The vast majority of Melilla's 30,000-plus Muslims don't think the same way the "strangers" do. "You give them the peace greeting and they don't even answer. They think they're the pure ones," says Mohamed, one of the gravediggers at the Arrakma Muslim cemetery.

Banned from school with a burqa

Chadia, aged 15, has not returned to Rusadir School in Melilla. A Spanish national, she dropped out during her third year because they wouldn't let her attend classes dressed in a black burqa, with her body totally covered, including a pair of gloves that went up to the elbow.

This past July she told EL PAÍS that she would enroll this year, but she hasn't. Miguel Ángel López, the school principal, says that they haven't heard from her. "The girl has to enroll. If she doesn't, she's outside the educational network. We don't know if she is still here or somewhere else. Now it's no longer a case of truancy."

Chadia (not her real name) still lives in Melilla with her mother, aged 42, in the same apartment, a rented 90-square-meter flat without an elevator, according to her neighbors. "She's not home. She'll be 16 years old soon and she'll be able to do what she wants," says another female voice, very similar to hers, from the other side of the door.

School is mandatory until the age of 16 and Chadia's birthday isn't until February, but supposedly she has not been enrolled. The Education Ministry and the juvenile prosecution office are going to take action. "I don't care if I miss the school year. If they won't let me wear a burqa, I don't want to study. I want to do something useful," she said in July.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.