The Reina Sofía's Raymond Roussel explosion

A walk around the Madrid museum's homage to the fascinating universe of the author

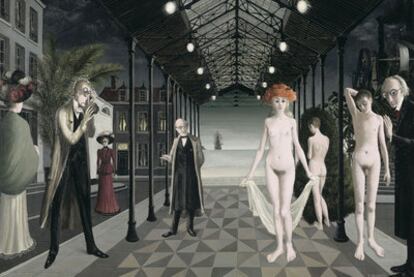

A new exhibition at the Reina Sofía contemporary art museum, Locus Solus, explores the extraordinary influence of Raymond Roussel's literature on 20th-century art. The more than 300 works on display reveal the importance of an "illustrious unknown" (in the words of Hermes Salceda), who was a role model for avant-garde artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Rodney Graham, Picabia, Roberto Matta, Man Ray and Julio Cortázar, among many others.

Museum director Manuel Borja-Villel and François Piron (they and João Fernandes co-curated the show) walked me through the exhibition of works by a turn-of-the-century man who, despite his later relevance, had to self-publish much of his own work during his lifetime (most of his publications were a failure) - and who died of a barbiturate overdose in Palermo in 1933, at the age of 56, after spending all of his considerable inherited fortune.

Salvador Dalí is present with numerous deliberate acts of delirium

Nobody talks about Roussel without quoting his famous writing procedure

The first surprise came in the lobby, where I could hardly believe I was coming face to face once more with one of the pieces from a watershed 1984 exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris on the Shandy culture of the "portable" artists of the 1920s avant-garde movements. Of that exhibition, the piece Le diamant (The diamond) by Jacques Carelman is the only surviving work inspired on Roussel's "machines" in his novel Locus Solus. The readers of that strange and brilliant book have surely not forgotten the diamond: "The monstrous jewel, which stood two meters high and three wide and was curved like an ellipse, reflected the sun in almost unbearable sparkles that adorned it with bolts of lightning going off in all directions."

Beyond the lobby, and following some surprising drawings by Victor Hugo (a Rousselian avant la lettre!), I thought I glimpsed, inside a case, the star that the astronomer Camille Flammarion gave Roussel on July 29, 1923 in his observatory at Juvisy. I don't know whether I saw correctly, but it could well be related to the Etoile sur le front (Star on the forehead), the engraved star that Roussel suspected all geniuses had. It was also the title of one of his books, and years later Marcel Duchamp drew it on the back of his neck and immortalized it in a photograph.

Soon after that, I walked into the rooms dedicated to Duchamp and Dalí, two of the artists who were more significantly influenced by Roussel, despite being as different to each other as night and day. Borja-Villel said that possibly Roussel was the only great point in common that allowed Dalí and Duchamp to feel united about something.

In the Duchamp room, together with his voluble Coffee Mill (1911) there is the diorama Étant donnés, which must be viewed through a hole made in a door constructed from Cadaqués wood, and which forces the viewer to look through one of two magnifying glasses set in a base. This device is reminiscent of the poem La Vue, written by Roussel in 1904, an endless description in verse of a miniature landscape, written on a crystal ball at the bottom of a fountain pen case. This crystal ball, by the way, and its minute description of meaningless objects, gave birth to the Nouveau Roman.

Salvador Dalí is present with numerous deliberate acts of delirium, such as El enigma sin fin (Endless enigma), and the movies that paid tribute to Roussel, Impressions of Upper Mongolia and Babaouo. I remember interviewing him in 1977 in his home in Port Lligat, and asking him about his relation to Roussel. Dalí replied that his own passion for this author had led him to make a movie that had won the Golden Mask on London television (Dalí always laughed his head off at awards). "But Roussel's method is completely different to mine," he added, simulating seriousness. "The paranoid-critical method, which I invented at least 50 years ago, still escapes me, but I do know it yields magnificent results. On the other hand, Roussel's method was a lot more about what we might describe as a kind of literary cybernetics."

These Rousselian cybernetics - forerunner to our digital era - are still not well understood, but they had a long-lasting influence on contemporary art. Nobody dares talk about Roussel without tediously quoting his famous writing procedure (based on a system of puns and phonetic combinations), which he revealed in a posthumous text, How I wrote some of my books, published in Spain in 1973.

As César Aira wrote in a sharp article in the magazine Carta, published by the Reina Sofía museum, there are three books by Roussel in which he did not use this technique (La doublure, La vue and Nouvelles impressions d'Afrique) and they are possibly more strange and original than those he wrote using the cybernetic method. This led to the question of whether there is a "unified key" to Roussel. Aira writes simply and brilliantly: "I think I have found that key: what everything that Raymond Roussel ever wrote, from beginning to end, has in common, is simply the occupation of time. He wrote in order to fill, in a solid and constant way, a vital period that would otherwise have been empty. To do that, he was forced to come up with ways of writing, frames and formats, that would occupy as much time as possible."

Locus Solus. Impresiones de Raymond Roussel. Until February 27 at Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Reina Sofía, c/ Santa Isabel 52, Madrid. www.museoreinasofia.es

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.