How the Church took the schoolhouse

A Navarre town is struggling to reclaim property that once belonged to the council

Around 1929 and again in 1934, the archbishop of Zaragoza, Rigoberto Domenech, attempted to register the landmark basilica of El Pilar as the property of his diocese, but the law prevented him from doing so.

Legislation had been curtailing the Spanish Roman Catholic Church's real estate ambitions for a long time, as the above story illustrates, because it forbade the Church from laying claim on places of worship.

But the advent of Franco's dictatorship signaled high times for men of the cloth. The Mortgage Law of 1946 gave clerics the same powers as civil servants, enabling them to register property of all types to their name: houses, cemeteries, empty lots, parks and so on. All except places of worship, that is. That exception remained in place until 1998, when the conservative government of José María Aznar eliminated the clause, opening the door to a slew of new registrations.

Before and after that date, there is ample evidence that the Church registered buildings to its name that were the proven property of towns; there were also double registrations to the Church and the town's name, and instances of towns that registered temples only to be sued by the bishops, and vice versa.

The case of Ziritza, in Navarre, illustrates the legal maze surrounding these registrations, and affords a glimpse of how this story might end for everyone involved: cities that have to pay public money to buy back what was once theirs, but changed owners thanks to a law that still grants the Church privileges from Franco's era.

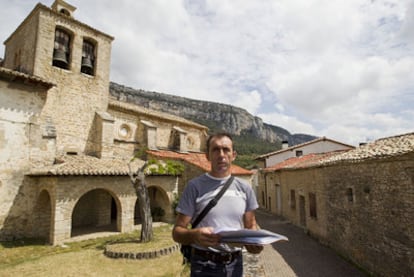

An imposing vertical outcrop looms over the small village of Ziritza, population 118. At 1pm, there is not a sound to be heard in town. Rafael Gorostidi, who was mayor of Ziritza until a few months ago, unlocks the door of the social center and deploys the pile of paperwork he built up during his four-year term; the documents extensively detail the ownership of all the religious and civil buildings in town.

A 1929 inventory of the council's possessions includes the schoolmistress' house, the school, the cemetery and more. How is it possible, then, that the schoolmistress' house and the school (now town hall) are registered as being the property of the Church?

The Church apparently took possession of both buildings. In fact, in 1974 and in 1994, it "ceded" the school so the council could set up the town hall there, and it also temporarily "donated" the teacher's house for housing purposes.

"Those documents seem to grant ownership of the buildings to the Church, which in any case registered them in 1980 without being stopped by anyone, even though they were unequivocally the property of the town," explains Gorostidi.

Lawyers told Gorostidi that if he wanted to get the schoolmistress' house back for the village, he should probably just buy it. The mayor reached an agreement for 50,000 euros. "Here is the document with the agreed terms," he says. But the Navarrese diocese ended up "selling it to a private buyer for 79,000 euros."

"They also wanted to sell the ground floor of the school along with the teacher's house, but I said forget about it, I have the deeds. There was no reasoning with them. So I built a wall and closed off the access," recalls Gorostidi.

The Church is selling, renting and possibly mortgaging property across Spain. Yet many towns are unaware of what is happening to properties that they believed were theirs. The United Left has requested information from the government on this "looting" and is asking for a legislative reform to put an end to it. For now, the ruling Socialists are keeping quiet.

"This is a national problem, and needs to be addressed as such"

Pedro Leoz, 81, is a diocese priest. For many years he was also a missionary in El Salvador. Now retired, his relationship with the bishopric of Pamplona is "purely economic" in nature. The Church pays him a complementary sum on top of his pension, although this payment was suspended for a year "because of my relationship with the Platform for the Defense of Navarre's Heritage, which fights to ensure that churches and others temples belong to villages."

Leoz confirms that once Church officials have the deed to a property, they can sell it, rent it and mortgage it. "They can even [use it to] make payments, as in the United States, where damages over pedophilia cases depleted the Church's coffers."

Leoz and other members of the activist group have written a book, Escándalo monumental (or, Monumental scandal) investigating these registrations by church officials in Navarre. But Leoz says that "the problem is national in scope, and needs to be addressed as such."

"We are getting requests for help and advice from all parts of the country. The battle must be a collective one, because it affects very small villages with no ability to deal with a lawsuit by themselves. The Spanish state should be the one to address this. We're talking about a vast cultural heritage and the trend is very widespread."

Church officials argue that they are registering buildings that were theirs to begin with, but Leoz notes that besides places of worship, they are also appropriating homes and schools.

"The churches were built with villagers' contributions and physical labor. What did they produce to be able to build so much? Besides, they register the temples thanks to a law that is unconstitutional. Forty years of Francoism left a deep mark and not everybody dares face up to the Church and raise the issue of unconstitutionality," he says.

Leoz and his fellow activists are recommending that mayors everywhere double check the title deeds of shrines, rector's houses and so on, and have the council register them to its name.

"If the Church already got to them, they should review the archives and document the ownership. We need to put a stop to this abuse."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.