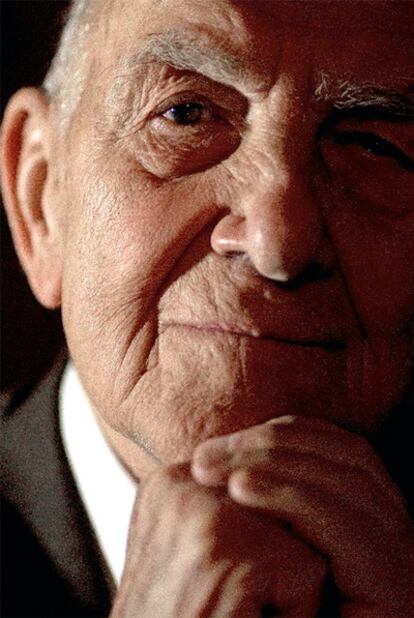

Stèphane Hessel: "Simply getting angry doesn't help"

At 93, the former French diplomat, writer and activist has managed to inspire the youth of Europe, in particular in Spain, with his book 'Time for Outrage!'

O n the table in the living room of Stèphane Hessel's Paris apartment is a copy of EL PAÍS with a photograph of what, in this context, can accurately be described as a group of "outraged" Spaniards, most of whom are in their twenties. The protests that have swept Spain, and seen the capital's Puerta del Sol square occupied for the best part of the last month, were initially convened under the slogan "Time for Outrage," taken from the title of the former French Résistance fighter's best-selling book of the same name.

At 93, Hessel still has plenty of fight left in him, and his book has captured the zeitgeist of the second decade of this millennium. The book is a call to rebel against the values that Hessel believes have led to a crisis that is eroding the achievements of decades of struggle and sacrifice: liberty, equality, justice, human rights, and the right to a job and a home.

"I don't believe in violence. I want people to work things out rather than fight"

"Nobody should be angered if someone commits themselves to something"

"When the Gestapo arrested me I was convinced that my life was over"

"I never imagined the brutality that humans are capable of carrying out"

Born of German-Jewish parents who settled in France in 1924, Hessel studied at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris and after the defeat of France in 1940 joined De Gaulle's Free French in London. Captured and tortured by the Gestapo during a mission to France in 1944, he was interned in Buchenwald and Dora, and cheated death by escaping during his transfer to Bergen-Belsen. After the war, Hessel joined the French diplomatic service and was one of the drafters of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. When the left came to power in France in the 1980s, he held a number of high-level administrative positions, speaking his mind even at the risk of ruffling his Socialist comrades' feathers. He authored a damning official report on France's practices of supporting corrupt dictators in Africa; the report was buried by President François Mitterrand, and the disastrous policy continues to this day (as was highlighted by France's diplomatic difficulties over the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions).

Hessel's ardent internationalism has not abated over the past two decades, and he has continued publicly to champion progressive causes, notably the construction of a more socially just Europe, the protection of the environment and the rights of illegal immigrants in France.

In the fall of 2010 Hessel published Indignez-vous!, a pamphlet that has sold over a million copies in France so far and has catapulted this venerable war hero into the limelight. Directed at the youth of his country, it is a rousing call to reject apathy and engage in a "peaceful insurrection" against all the injustices that blight the contemporary world: the continuing exploitation of the developing world by rich countries, the abuse of human rights by despotic governments, and the iron grip of mercantilism over the body politic, threatening the achievements in economic and social welfare for which his anti-fascist generation fought.

Question. Your message has been taken up in Spain, with thousands of people marching and protesting against a political system seen as bankrupt.

Answer. I'm glad. When we first thought of the idea of this small book, we had France in mind. Soon after it was published, several important things happened. Sarkozy's popularity plummeted, as did Berlusconi's and Zapatero's. People are tired of governments whose behavior has angered them in a way that has rarely been seen before.

Q. So you decided to put your ideas into a book?

A. It's not a work of literature. We wanted to send out a short, inspiring message. It didn't take long to write. It was a very natural process, like a conversation. But once it hit the streets, the word spread very quickly.

Q. People have been waiting for somebody to express their sense of outrage.

A. As we have seen. The book is really two texts: one is about the résistance, about how the French stood up to the Nazis. The other source is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Q. You participated in writing that text.

A. I was too young to be part of it, but I was present. I helped organize meetings.

Q. Why did you decide to call the book Time for outrage?

A. Actually, the title was decided by the book's editor, Sylvie Crossman. But I immediately accepted it. I don't consider myself a revolutionary. I am a diplomat, and I don't believe in violence. I want people to work things out, rather than fight each other.

Q. That's radical enough these days...

A. We are surrounded by politicians who are always getting us into wars. Is dialogue such a revolutionary idea? It might be. But if we look at the title, it is about dignity. When our dignity is at stake, we have to react. Outrage comes when our dignity is trampled on. That is why I always refer to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The first article says: All human beings are equal in dignity and rights.

Q. So you are appealing to people's sense of commitment...

A. The new book is called "Commit Yourselves." It's the next moral step after outrage. Nobody should be angered if another person decides to commit themselves to something. They might be angered by rebellion, which most likely will benefit others, like the far right. I am in favor of indignation in another sense; when our basic rights are attacked. But simply getting angry doesn't help. Anger in itself goes nowhere - it must be backed by commitment.

Q. That's not easy.

A. I'm not suggesting that people should just get angry, but that they should ask what it is that threatens our fundamental values, the values we have inherited, and that are now under threat. That isn't easy. The book makes it clear what the values we need to defend are, and what the threats to them are.

Q. Are the values of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights under threat?

A. They are. But let's not forget that when that document was written, the world was threatened by totalitarianism. Fascism had been overcome, but communism still survived. Then came the twisted ideology of the markets, the faith in the markets, and nothing else. Today, you and I are suffering the consequences of the actions of what a privileged minority has done at our expense. And the only alternative is real democracy.

Q. It's a nice expression.

A. We have to give more power to ordinary people so that their needs are addressed by governments: that is our first task. Governments have to guarantee liberty, fraternity, equality and social justice.

Q. Progress is another concept that is in crisis. We tend to confuse it with technical development rather than with wellbeing.

A. Absolutely. It is really very simple: progress means moving toward things being better. The better is important. What is the difference between good and evil? Is it better to earn money at any price or to preserve decency and honor? Is it better to enter into a spiral of scientific progress at any cost, or to protect ourselves from discoveries that threaten human dignity? Progress doesn't mean to go faster, but to be aware of the values that make for a better world. Democracy is demanding. It requires politicians to help create a system where it is difficult to come off well if you do wrong.

Q. So let's get back to the different shades of meaning to be found in the word "outrage."

A. I am not a violent man. I can understand that people sometimes resort to violence. But I don't believe it works. My first sense of outrage had a name: Nazism. The fascism of Franco and Mussolini, and Stalin. Totalitarianism. What's more, we had examples of extremism in both sides of the Spanish Civil War. I consider myself a democrat, and when that system was in danger, I was outraged. But the First World War made many of us believe that we had to exhaust every possibility before resorting to violence. It was only when I saw that those people wanted to conquer Europe that I realized we had to fight them with weapons.

Q. And do you really feel the same sense of indignation now?

A. No. I was younger then, and wanted to fight. When the time came, when I saw that we had to fight, I was filled with the desire to fight. I joined the army without hesitation. And when the armistice was signed with the Germans, I was outraged. I felt that it was dishonorable, and disloyal to the British. It was unacceptable. So I did the only thing I could, which was to join De Gaulle.

Q. And you had an intense relationship with him...

A. No. I was very young, and a low-ranking officer. But I was privileged to meet him. He wanted to know what a young student from the École Supérieure thought about him. He wanted to know what the students thought about him.

Q. Fortunately, De Gaulle was also outraged, unlike most of the rest of France.

A. The country had been hit hard. What happened in June 1940 was very rare in history. It wasn't just a military victory. It was a colossal defeat, humiliating, and people had to flee. For many, the armistice was a relief. Peace was a very tempting proposition, but of course it wasn't real peace.

Q. Was it humiliating?

A. Of course, and there were other factors. The threat of communism terrified the bourgeoisie, more than the fascists. What's more, the Nazis were a guarantee against the communists.

Q. You were arrested by the Gestapo...

A. When they arrested me I was convinced that my life was over. I was charged with serious crimes. They knew that I had traveled to London to work with the résistance.

Q. And of course you were Jewish...

A. They didn't know that. They didn't really know who I was. If they had, they would have treated me very differently. They thought that I was a spy, so they tried to get information out of me.

Q. You were tortured?

A. I was. They drowned me, but they didn't get me to give anything away, and that was of enormous satisfaction. Then they condemned me to death. Fortunately, justice was slow, and they locked me up in Buchenwald, and the order to hand me over arrived very late. In the meantime, I was able to take the identity of somebody who had died. So I survived.

Q. I imagine that your outrage turned to terror...

A. Not really. It changed into something that only a young patriot can feel. That feeling that you have done your duty, and that you have made a sacrifice for your country.

Q. So you were a hero.

A. Let me tell you something. When they arrested me, I found a piece of paper and wrote down a sonnet by Shakespeare that I had learned by heart: "No longer mourn for me when I am dead." It was as though I were saying, if they shoot me tomorrow, then let my widow know that I don't want her to mourn for me. Ridiculous, the whole thing is always ridiculous.

Q. It is a noble enough way to face death.

A. Life is full of ironies.

Q. And if somebody had told you that you would live to 93 years of age...

A. My next feeling of outrage came in the camps. I knew that war was violent. But I never imagined the brutality that humans are capable of carrying out.

Q. You went from feeling like a hero to being a victim.

A. But not just an individual victim, part of a collective. Because I was lucky. I was one of 36 sentenced to death who survived. Me and two others. I was sent to another camp, and I escaped. When they recaptured me I was sent to Dora. There they couldn't decide whether to hang me straight away, or give me 25 lashes. But I escaped both because I told the officer who interrogated me that he too would have tried to escape. I was able to talk to him in German, which is my mother tongue. That is probably what saved my life.

Q. There have been happy times in your life as well. It must have been quite a sense of achievement to bring so many different countries together to sign the Universal Declaration of Human Rights...

A. If we hadn't managed it in 1948, the subsequent tensions would have made it impossible later. The Soviets abstained, as did the Saudis, which allowed it to be approved by the UN. It was a defining moment, an ambitious text for humanity.

Q. So your sense of outrage turned to hope?

A. Yes, that is true. That moment was one of real hope that the nations of the world had come to understand each other following the war. We were convinced that that text would put much of the world on the path to freedom and justice. But of course it didn't last long, because soon after came another feeling: the anxiety produced by the threat of a third war, which wouldn't be like the others, but would lead to nuclear holocaust. The world had known two horrors already: the Holocaust and Hiroshima, and we were frightened by them. The world was a complicated and insecure place. We felt that if the UN was not successful in its development programs and in advancing respect for human rights, everything would collapse around us.

Q. Do you retain any of your optimism from that time?

A. I think that we can still make small steps forward and that we will move forward, albeit with occasional steps back. The last decade of the 20th century was very promising. After the fall of the Berlin Wall we were convinced that we had entered a new era. In 2000, we reached an agreement under the director generalship of Kofi Annan regarding the Millennium Goals. Then the Twin Towers collapsed... and we started the 21st century very badly.

Q. There was the threat of terrorism, but also the decision by Bush and Blair, and Aznar, to go against international law. What did that mean for world order?

A. That is part of what also outrages me. The fact that we all knew we were making progress and that these leaders just slammed the brakes on, and turned us in a different direction. The wrong direction.

Q. Wasn't that little more than just fascism dressed up as crusade for democracy?

A. Absolutely. One of the basic rules that needed to be obeyed in the new world order that began to take shape around the end of the 20th century was international law. By breaking it, things have just gotten worse.

Q. So what can we do to wake up our ignorant governments?

A. Time for outrage! We need other leaders, and we also need to support the better leaders that we have. We can't fall into the trap that so many young people do of just giving up, nor should we believe that all politicians are the same, because that isn't true. Anger and indifference will get us nowhere.

Q. There is another reason for your outrage: Palestine.

A. Once again, the rules of international law were broken, brutality imposed. The situation in Gaza and the West Bank represents everything that I detest; similar to what I felt in the concentration camps. I have a great appreciation for the state of Israel, but when its government behaves in the same way as the worst governments that I have known in my life, I just cannot accept that, and I have to react and condemn the abuses that are sanctioned by the EU and the US and many large corporations that are involved. It is the same frustration at the inability of the world to agree on climate change. I hope that Obama, now that he has finished off Bin Laden and improved his popularity, will now be able to make progress in other areas.

Q. What is your assessment of Osama Bin Laden's assassination?

A. I am glad that he has been finished off. He was a murderer capable of terrible things. Perhaps his greatest crime was to give Islam a sinister image. Islam is not like that. The peoples of the Arab world have shown us in recent months that they are guided by common sense in rebelling against their governments. But returning to Bin Laden, it would have been better to arrest him, and to try him.

Q. And what about the growing mood against immigration in Europe?

A. That is exactly one of the objectives of my book; to make people more able to deal with the new challenges we face with dignity. It isn't our countries that are at risk, that are at stake, it is the world itself. The world is under attack by the neo-cons and the others who refuse to address the issue of climate change and the environment. We must have faith, and stick to our commitments. We are not condemned to failure, but we have to move forward if we are to succeed.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.