The Alhambra's profane pictures

Restorers have discovered 80 drawings of animal and human figures - proscribed by the Islamic culture of the time - hidden beneath the walls of the palace

In 1959, during the restoration of the Hall of Ambassadors inside the Palace of Comares- part of the famous walled citadel of the Alhambra in Granada- the workers came across some paintings behind the wooden boards covering the ceiling. Nobody thought much of them at the time. It was assumed that the flowery motifs were just a minor curiosity, or perhaps that they had been made to help the craftsmen determine the proper order of the wooden ceiling boards.

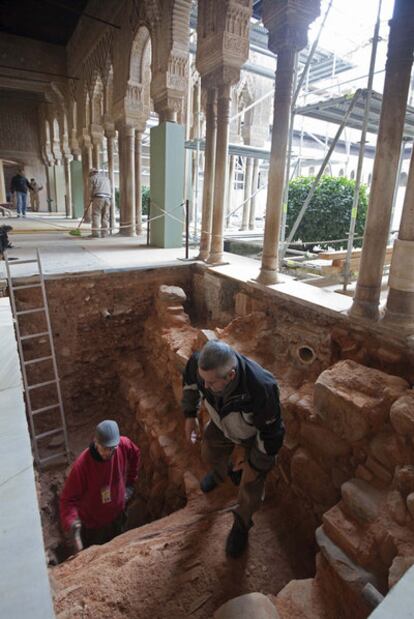

Then, several months ago, restorers received another surprise while working on a different area of the Alhambra called the Mirador de Lindaraja. When they took down the wood and plasterwork there, they found a collection of over 80 drawings originally made by the artisans who decorated the Nazari palace.

"The Alhambra has been frequently restored. It has undergone many changes," explained María del Mar Villafranca, director of the Alhambra and Generalife Trust. "Yet these drawings have remained hidden all this time and they are still in their original state; they are wholly authentic, which makes them very valuable."

The drawings display a great variety of subject matter and their original pigmentation has not changed.

Vegetables, fantastic creatures, verses from the Koran that have yet to be translated, building instructions for the craftsmen... all those and more are in there.

There is also a real treasure for Nazari art historians: an anthropomorphic figure. Its head rests on the body of an animal which might be a dog or a cat. The strokes are perfect and the drawing is so well-preserved that it might have been made yesterday, rather than centuries ago- unlike the wooden structures that concealed it, which had become faded by centuries of damp.

"It is very hard to know why they were made, but our guess is that these are spontaneous creations made for fun, which were never used to decorate the palace," says Elena Correa, the head of the restoration department.

In recent years, many hidden treasures have sprung up from behind the walls of the Alhambra citadel, which remains an endless source of history and curiosities. The fact that a human representation was found at all is no small matter, since such images were banned in most Islamic art.

"There are several periods within Muslim art," says Villafranca. "When a literal interpretation of the Koran was favored, [depictions of human forms] were banned, and it is unusual to find any. This is a discovery that at the very least is highly original, which proves that during Nazari times there were artists who were challenging the ban and depicting animals and people."

The Koran states that it is impossible to obtain an image of God, and furthermore suggests that no artist can compete with the divinity when it comes to creating real beings.

This had huge implications for the history of Muslim art, to the extent that any image relating to the human body was avoided and persecuted- except those expressly created for the decoration of private rooms. Thus the penchant for geometric shapes with their characteristic red and gold tones.

"During the decoration of the Alhambra, these figures were no doubt frowned upon," said Villafranca.

"Their authors would be persecuted, so those who made them must have felt some fear. All these drawings were walled up; they were just bits of mischief."

Yet the trust director does not rule out another possibility: that they were sketches or "a way for them to practice," since there is no link between the drawings and the ornaments placed over them.

In some parts of the world where there was greater tolerance, these pieces of mischief were bigger.

For instance, in the Msatta Palace in the Syrian desert, which dates from the beginning of the 18th century, you can clearly appreciate the distinction between the secular and the religious rooms.

In the former there are zoomorphic representations that have a strictly decorative purpose. The Alhambra drawings show some similarities, but are much more spontaneous and have more urgent lines, which suggest they were made clandestinely.

"There are no set guidelines. [The drawings] are very spontaneous and that forces us to analyze them very carefully. We don't want them to simply become another reference in an art history book; we want to make the most scientific analysis possible," says Elena Correa.

Besides depicting human shapes, some of the Alhambra drawings are signed, which is also a very strange element in the context of Islamic art.

"Nazari artisans did not leave their names behind, they worked anonymously. It's possible that they were by someone of great importance on the decoration team. We have to keep in mind that what we think of as an artist today had no place in their concept of the world. The people who made those drawings were mere workers, craftsmen in a workshop," adds Correa.

There are many mysteries surrounding these uncovered drawings and many of the answers to them will be obtained through the research being carried out at the wood restoration workshop in the Alhambra.

For now, however, analysts have completely ruled out the hypothesis that they might have been made after the rooms in which they were found were decorated.

"They were not done by Christian craftsmen. They were done by the same people who decorated the palace," says Villafranca.

It is exciting to imagine those craftsmen who were able to create amazing architecture through their knowledge of geometry, secretly drawing these little figures and concealing them, like tiny pieces of childish mischief, under the impressive calligraphy of the Koranic verses, behind the solemnity of works of art that strove for greatness.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.