The man fighting for peace in Lebanon

Alberto Asarta is the first Spaniard to lead a UN operation. His goal is to end decades of hostilities

"Some people are born scared shitless, but I'm not one of those people," says General Asarta with his proverbial aplomb.

"When Spain has needed me, I've never taken a step back. I follow orders and make others follow them. In this country, I'm responsible for a peace-keeping mission, and I demand that my blue helmets are as clear about their duties as I am; that they're just as scrupulous about the rules of confrontation; that they respect the traditions and religions of the Lebanese people; and that they be exemplary. We're in Lebanon to solve problems, not to cause them. We've come to collaborate, not to fight, although if we have to get involved, we will. But in the meantime, we've got to keep on working hard to avoid it. History shows that in Lebanon, life spent scared shitless isn't worthwhile."

"We're in Lebanon to solve problems, not to cause them. We're not here to fight"

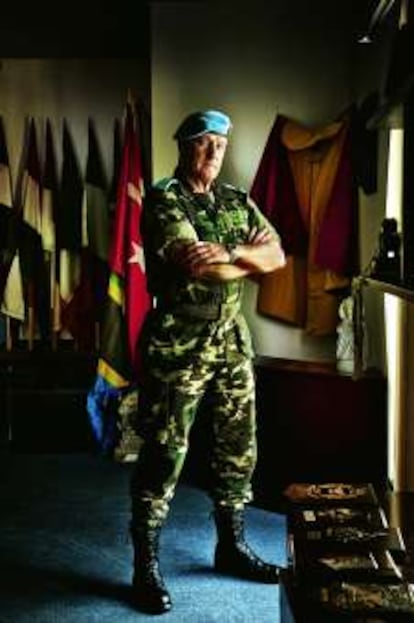

His sleeves are rolled up over his biceps and his boots shine like mirrors

Alberto Asarta is a direct, assertive man from Aragon with a powerful build that is the product of 500 parachute jumps, years of service in the Legion and hundreds of kilometers of marathons. Now nearing the age of 60, he still usually goes out for an early-morning run, surrounded by bodyguards, between the barbed-wire fences that protect this military base in Naqoura, in southern Lebanon. He projects the image of the perfect soldier. He likes to cultivate it. He wears a blue beret, the sleeves of his uniform are rolled up over his biceps and his boots shine like mirrors. And he likes being described as a leader: "I've spent my entire life preparing for it."

The son and brother of military men, he prides himself on having been brought up with values that now sound outdated: discipline, bravery, comradeship, sacrifice. They're his style manual. Asarta is a conservative, but not a nostalgic big-shot. He's more along the lines of the new US generals who are all over the media. An educated staff officer, he speaks English and French well and defines himself as apolitical. "As a military man, I represent the needle of balance." In this regard, it's hard to catch him out. When I show him the record of the Congress session of September 7, 2006, where Mariano Rajoy criticizes the Spanish army's involvement in the Lebanon mission ("It must be admitted that in all honesty," the opposition Popular Party leader said, "that the operations under the UN mandate have been a failure, and in some cases, a total disaster") and I ask him for his opinion on the matter, he refuses to comment: "I don't discuss politics."

When I point out that he's politically in charge of this UN mission, he says: "My duties involve being on the political level, but I'm not a politician. I'm a military man. And anything I say can be misinterpreted. My mission is to lead the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon [UNIFIL] and apply Security Council Resolution 1701 from August of 2006: to monitor the cease in hostilities with Israel, to avoid hostile actions in our area, to help the civilian population, to support the deployment of Lebanese armed forces in this part of the country until they can manage on their own and establish an arms-free area between the Blue Line - the line of Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon, which we are demarcating - and the Litani River: to de-mine, reconstruct, help the Lebanese government - if they ask us - to keep weapons from entering that territory, to try to get the different parties to talk to each other... We must create a safe, stable environment conducive to a permanent ceasefire and the beginning of a peace process. And to do this, I deal with politicians. I listen to them and try to convince them of the need for peace. Our role is to mediate. The conflicting parties have asked us to come and help them. That's what gives us our legitimacy."

Asarta's work as a mediator is most clear during the tripartite meetings, which he attends every month with senior Israeli and Lebanese officials. It's the only channel of communication currently open between these two countries, who have no diplomatic relations and have never signed the end of a conflict that has drawn out for 30 years. The meetings take place in no man's land, at United Nations Position 1-32A. It's a desolate, surreal place defended by Italian cannons, where there is no sign of life other than a bare little building whose roof is guarded by sharpshooters. To get there, you have to go through several security checks. Asarta is the first to arrive. His carrier moves forward, preceded by armored vehicles from the Indonesian army with machine guns sticking out of them. When he gets down from his vehicle, he is surrounded by his personal protection team: a dozen elite Spanish soldiers. Next to arrive are the Israeli generals: young, casually uniformed with submachine guns slung over their shoulders. Then the Lebanese show up: they are older, more severe and inscrutable, with Arab mustaches and black berets. Asarta receives them separately. They take their places at a square table inside the building. They don't look at each other. Asarta acts as host. The atmosphere becomes so tense you could cut it with a knife. Asarta defines these meetings as "military and technical; we deal with issues such as the demarcation of the Blue Line and possible armed incidents that may have taken place in the area, and any grievances are put on the table. These meetings play a fundamental role in promoting dialogue and trust between the two parties. If they're willing to fix some of their differences through dialogue, then we'll have taken a step toward normalization."

The tripartite meetings are secret. The Lebanese generals demand that we leave, which we do. At that moment, an Israeli combat plane shoots through the sky. According to UNIFIL, Israeli jets on reconnaissance missions violate Lebanese airspace on a daily basis. The Israelis say that these flights will continue until the Hezbollah militia hands over its weapons, and vice-versa. "Both sides are right; both are violations of [Resolution] 1701." says Asarta. "Both parties are obliged to uphold the agreements; we're witnesses and arbitrators, but we can't force them to comply with the resolution. We can't prevent the Israeli flights or search Lebanese homes. I haven't seen those Hezbollah arsenals that Israel talks about. But I do have evidence that [Lebanese] airspace is being violated. And as for disarming the militia, that's not our responsibility - it's the Lebanese army's, and we're willing to help them if they ask us to do so."

Alberto Asarta is the first Spaniard to lead a United Nations peace-keeping mission since they were first set up in 1948 to observe the ceasefire between Israel and Arab nations. The international community has invested him with full authority. He's responsible for the mission; he represents the secretary-general of the UN and he is the force commander. During a mission of this kind, the troops from each country are under the control of the United Nations via the force commander. Asarta must be a combination of soldier, diplomat and arbitrator; a "good guy" who applies carrot-and-stick methods to keep the unhealed wound between Lebanon and Israel from opening up again. To achieve this, he's got more than 12,000 soldiers from 35 countries, plus armored vehicles, artillery, missiles, radar, frigates and helicopters. Spain has more than 1,000 men and women deployed in Lebanon's Eastern Sector. Asarta has also got a team of 1,000 civilians from 80 different countries and an effective international cooperation apparatus to rebuild infrastructures in southern Lebanon and reactivate its economy through "quick impact" projects and micro-credits. This formula has already been applied in other countries in conflict, such as Afghanistan, to win the hearts and minds of the people. The key is for the Lebanese not to perceive the blue helmets as an occupying army, but as a peace force.

"We can't go against Hezbollah, for the simple reason that it's a legal organization, which is part of the government and is recognized by the Lebanese president himself as one of the pillars of the country's defense. They're an important part of the populace here; we've got to live with them... We've got to win people's trust and at the same time, get the Lebanese army to take control of the situation."

Asarta belongs to the first generation of Spanish officers who went abroad after being kept at home for four decades under the Franco dictatorship, in charge of protecting the country. In the early 1990s, when he was a young commander, he participated in a peace mission in El Salvador. After that he was assigned to places as different as Bosnia, Strasbourg, Argentina and Iraq. In the latter country, in April 2004, he ended up engaging in combat against the Islamists of the Mahdi army, who were trying to attack the Spanish base he was controlling in Najaf. The skirmish ended with dozens of Iraqi casualties. The images from those days show the left-handed Asarta, in a helmet and bulletproof jacket, opening fire at an invisible enemy from between sandbags. For his performance in combat, Prime Minister Zapatero gave Asarta and five of his soldiers the Military Merit Cross. During the course of our conversation, when I remind him of those terrible scenes, he goes back and forth between the pride of the soldier who has won a war and the sadness of a man who has seen death on the battlefield.

"I'll never forget those days; the insurgency attacks... I called my wife in Spain and said, 'They're attacking us again.' And she could hear the explosions... We took it well. It was my duty. When I got back to Spain I was in rough shape. They are things that you don't like to see; they affect you. I think we did what we had to do and we all made it back alive. I have no regrets. We didn't go to Iraq to wage war. But in the end, things turned sour. We acted in accordance with rules of confrontation that were very restrictive about the use of force. During the battle, we didn't shoot at ambulances, even though we knew they were carrying soldiers; we didn't shoot at those who were pretending to be dead; we didn't destroy buildings that might have had civilians inside, even though there were sharpshooters there. My orders were to fight defensively. We had a set of rules. And if we broke them, we could have ended up in court."

"Did you kill anyone?" I ask. - "I prefer not to think about it."

The prayer call from a mosque near the UNIFIL headquarters can be heard in the general's office. It is spacious, conventional and sparsely furnished, like everything else in this United Nations complex, which has gone from a group of tents in the middle of nowhere to a huge military and logistic complex that meets the needs of the 12,000 soldiers deployed south of the Litani. The premises are surrounded by a wall of concrete blocks. In front of the Force Commander's desk is a picture of him parachuting in 1978. "That way I don't forget where I came from. For the grace of God, free me from carpets. Offices can make you lose your mind."

Asarta insists that he's a man of action; a man who's happy on the ground passing round a wineskin, or sharing a hookah, the oriental pipe that he's taken a liking to in this country. He likes to mix with his soldiers. We see this on a visit to Marwahin, an area along the Israeli border, where a team of Italian sappers is cleaning the area of landmines. The Israeli army buried thousands of them before retreating. They are little brown plastic boxes containing 80 grams of explosives that blend into the landscape. Their objective is to mutilate, and removing them is a high-risk operation. Asarta jumps down from his helicopter and greets the troops with affection, repeating his usual messages: "I'm one of you."

Close up, the general seems like an overconfident, empathetic, backslapping kind of guy, prone to bear hugs and big smiles, elements that are useful for him in his relations with the tribal bosses. He knows that he must win their trust. If the UNIFIL troops make a wrong move, it could offend the Lebanese, irritate the militia and cause an outbreak of violence.

A year ago, after being appointed commander of UNIFIL, a group of friends gave Asarta a bullfighter's cape with his general's stars embroidered on it to wish him luck. He was going to need it. This small nation - which is trapped between East and West, between Saudi oil money and the Iranians, and is struggling to maintain a precarious balance between the 17 different religions that form it - has received thousands of Palestinian refugees and is just a stone's throw away from Israeli forces in the Galilee Division. Around 200,000 people have died in the confrontations since 1975. In 2006, during the 34 days of undeclared war between Hezbollah and the Israeli army, 1,500 Lebanese nationals and 120 Jews died. Entire neighborhoods in the Shiite suburbs of southern Beirut were razed by Israeli air attacks and 100,000 homes were destroyed in the southern part of the country. In its campaign against Hezbollah, the Israeli military took out bridges and highways, roads, airports and power plants. In Beirut, you can see the evidence of the bombings in Dahieh, the Shiite ghetto where Hezbollah controls everything, even the traffic. This is especially true in the south, a territory that has been occupied by Israel for two decades. During that period of resistance, Hezbollah, the "party of God," had a monopoly on political and religious power as well as social services. This organization still has de facto control over this territory of 2,500 square kilometers and 700,000 inhabitants surrounded by a 121-kilometer border with Israel. Last October, its people received a visit from the Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, as their natural leader.

"This is a checkerboard with black-and-white squares, but there are also other players, who are playing other games on the same board at the same time," says Asarta. "Their game is taking place on this territory and influences it. Today, a conflict could break out in Lebanon that has nothing to do with the two countries that are playing the main game. That's why our mission is being carried out in a much broader context than the area of operations under our authority. What happens in Palestine, Egypt and Iran could upset the fragile situation in Lebanon. And that makes our mission very unstable. There are clearly interests at stake here that aren't exactly the interests of the Lebanese people."

Crossing southern Lebanon from Naqoura to Marjayoun, where the Cervantes base and the Spanish troops are located, allows us to immerse ourselves in Hezbollah territory. Each village that we pass through was hit hard in the 2006 bombings. Still-visible damage from the bombs clashes with new homes and small businesses, which have been financed by money sent from abroad and have cropped up during these last four years of peace. At the entrance to each town, we are received by swarms of yellow Hezbollah flags decorated with Kalashnikovs, the portraits of Islamic kamikazes and images of Khomeini; the squares of Tibnin, Tulin, Markaba and Ett Taibe are decorated with pieces of weaponry stolen from the Israeli invader. Everything suggests war. It's impossible to take any pictures; Hezbollah does not permit it. At strategic points along our route, there are groups of young, bearded men with motorcycles and cellphones watching our vehicles. Many of the women are wearing chadors. In Al-Adaisseh you can still see the ruins of an army post bombed by the Israelis in August after a confrontation along the Blue Line that claimed four lives.

But where the tension between Lebanon and Israel can best be seen is in the Israeli town of Metula. There, soldiers from both sides come face to face almost every day; they spit and point their weapons at each other, and hurl insults. "The stupidest little thing can provoke an exchange of gunfire, and that can lead to war," says Asarta. "We've got to pay close attention to the Blue Line. One of our concerns is to avoid such incidents, which can lead to thousands of deaths."

A few kilometers before we reach Marjayoun, there is a little monolith on a road without a name in memory of the six Spanish soldiers who died there in an attack on June 24, 2007. Who killed them? Nobody seems to know. Fatah al Islam, a Sunni terrorist group with ties to Al Qaeda and an enemy of Hezbollah, claimed responsibility. But in Lebanon, anything is possible. War is deeply entrenched, and many think that UNIFIL's work is just another Band-Aid solution from the international community. Asarta doesn't agree. An inveterate optimist, he has coined a slogan for this land tormented by 30 years of war, which he thinks will be able to live one day in harmony: "If you're looking for peace, come to the South."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.