No miracles in the land of miracles

Latin America, the land of supernatural occurrences, has had just one episode of spectacular economic growth, which occurred in Venezuela in the 1940s and 50s

Mexico has its Virgin of Guadalupe. In Colombia, the Virgin of Miracles is the patron saint of Tunja. In Lima, the Vicentine Brothers have a parish dedicated to the Lady of the Miracle of Lima. In Argentina’s Salta province, the Lord and the Virgin of the Miracle is venerated. The patron saint of Brazil is Our Lady of Aparecida, whose following goes back to 1717 in the Villa of Garatingueta, where a group of fishermen discovered her image and then made a miraculous catch. Miraculous figures are ubiquitous across Latin America.

But economists and politicians across the continent have been less efficient when it comes to producing economic miracles. Economics and politics have little or nothing to do with folk beliefs.

Looking at data on economic miracles, Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Lucas, from the University of Chicago, and professor Luis Felipe Sáenz, from the University of South Carolina, found that since the beginning of the last century, around the world, a considerable number of economic miracles have appeared. They define as a “miracle” an episode in which a country’s GDP or value-added per capita doubled over a decade.

They compare the results with the United States economy: an economy is doing well when it moves closer to the most advanced economy in the world, not just when its local businesspeople are making money.

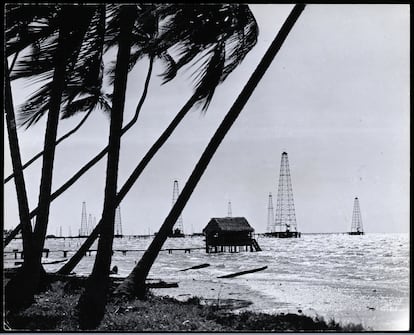

A devastating fact is that Latin America, the land of miracles, has just one economic miracle, which occurred in Venezuela during the forties and fifties.

The contrast with other regions could not be more devastating: in Africa, 11 countries had economic miracles. In Eastern Europe, 11 countries did, mostly in the last 20 years. In the Middle East, there were eight economic miracles, some of them linked to the petroleum boom in the sixties and seventies, and others as recent as 2005 (Iraq and United Arab Emirates).

In almost all the countries of Western Europe, except the United Kingdom and Spain, the miracles occurred in the fifties. Ireland had its own during the turn of the century and Ukraine in 2007.

The Asian tigers exhibit the most lasting miracles, with South Korea at the head, between 1971 and 1995, three spectacular decades for the country, longer even than Japan’s miracle, which occurred between 1959 and 1974. Singapore and Taiwan had their golden decade in the 1970s and China in the first decade of the 20th century.

Lucas and Sáenz attribute that sudden growth to three factors: first, access to technology, especially technology that rapidly develops modern sectors and attracts people to industries and cities; secondly, the demographic transition, during which the population has fewer children and invests more in their education; and third, the participation of women in the labor force. Women tend to participate at the beginning of the development period, then leave the labor market. When the country is wealthier, they return en masse to work.

We return to the land without miracles. What happened to Latin America? Why does the continent have so few episodes of sudden, spectacular growth? Since the end of the 19th century, there was a clear difference between two groups of countries. Argentina and Chile began the 20th century far above the rest of the region. Until 1940, Argentina’s GDP per capita was close to 60% that of the eUS, and Chile’s between 40 and 50%. Nothing similar was seen elsewhere.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Venezuela and Mexico’s GDP per capita was barely a fifth of that of an average person in the US. And in Brazil, Colombia and Peru, productivity per person was around 10% that of an American.

Some interesting, but not miraculous, things started happening. Colombia and Peru grew dramatically between 1910 and 1940. In the mid-thirties, Venezuela experienced a spectacular leap that didn’t end until 1950, when the income of an average Venezuelan was around 70% of the GDP per capita of the US. It was the only Latin American country to reach that level.

As Venezuela skyrocketed, the decline of Argentina and Chile began. Chile declined until the mid-seventies and Argentina until the mid-eighties, both seeing their per-capita GDP fall to half that of the US.

What happened in Brazil, Peru and Colombia during that period? Brazil started from a very low point in the forties and grew until 1980. During those four decades, Colombia and Peru remained stable, their GDP per capita neither growing nor falling.

That marked the beginning of the “lost decade,” the global economic tsunami caused by the increase in interest rates of the American Federal Reserve, intended to control inflation, as it is doing now.

From then on, Venezuela suffered the most: in the last two decades of the previous century, it lost all it had gained since 1930. Argentina also plummeted. Brazil, Chile and Mexico fell, but less dramatically. Peru dropped to the last place in the region. Colombia was not affected by the debacle of the eighties, but it continued to have a low GDP per capita.

The 20th century brought an economic rebirth. Chinese dynamism at the beginning of this century increased the price of raw materials and demand for the region’s products. Between 2000 and 2014, there was an economic boom throughout the region. China’s rising tide lifted all the boats.

Chile mentions a special mention. It quickly left behind the crisis of the eighties, experiencing a notable transformation —though not a miracle, according to the aforementioned definition— which it managed to maintain for three decades. By 2015, Argentina, Chile and Venezuela led Latin America in terms of GDP per capita, close to 40% of that of the US. Mexico and Brasil followed at 30%, and Colombia and Peru closed at close to 25%.

The story of ups and downs has not ended. Halfway through the last decade, China lost dynamism, which affected the demand of raw materials. Additionally, fracking of petroleum and gas in the United States sunk crude prices dramatically.

Venezuela fell to the last spot in the region. Argentina and Brazil also fell, though less severely, to the point that we can say that the three countries each lost a decade. The situation is so dramatic for Argentina and Venezuela that it can be said that they lost an entire century.

Recent history has been less difficult for Chile, Mexico, Colombia and Peru. The four countries that make up the so-called Pacific Alliance stayed afloat without winning or losing compared to the US, with Chile at the top, Mexico in the middle and the other two below them.

When examining the patterns in this difficult 100-year economic history, to explain the absence of miracles, we can emphasize three factors: the lack of consistency that cut off often-prolonged periods of prosperity; incomplete transitions from rural to urban, and from having many to few children, with access to education; limited access to technology and world markets for products besides raw materials; the entrapment of million of women in care work, which keeps them outside the labor market.

Some authors blame the lack of consistency of our institutions or the incomplete connection with international commerce. Others cite the insufficient access to ever-changing, up-to-date technology, and others a challenging geography, which, with the Amazon, the Andes, the Panamanian isthmus and the enormous distances that characterize the continent, make its internal integration costly and limit the easy contact with the rest of the world. Finally, some cite culture and politics.

Every hopeful episode, even those that last a few decades, is followed by a crash, or at least a long, insufferable plateau. We stop what allows us to progress, stifle the early blossoms of growth, or, worth, fall into errors that send us half a century into the past.

Prayer clearly is not enough, but neither is applied economic science and politics. How can we avoid another 120 years of solitude? Can we keep populism at bay? Will there be another super-cycle of raw material, as at the beginning of this century? Can the so-called critical minerals, like lithium and copper, make a difference? Will the phenomenon of nearshoring and industrialization stay in Mexico? Is there any future in the integration of the region, as Lula, López Obrador and Petro imagine? They are questions that we should answer every day, but we spend more time fighting over ideology.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.