Rio funk: The stigmatized dance that reigns in Brazil’s favelas finally enters the museum

The Rio Art Museum has dedicated this season’s grand exhibition to telling the story of the rhythm born in the city’s marginal neighborhoods, which combines African-American soul music and Indigenous elements

In the middle of an afternoon on a weekday, seeing such a long line to enter a museum in Brazil is quite striking. Even more extraordinary is that a good part of those waiting to buy tickets are under the age of 30.

The exhibition, Funk: A Cry of Boldness and Freedom, has been a huge success since it opened three weeks ago at the Rio Art Museum (MAR). Through 900 works and objects, it reviews the history of this rhythm — Rio funk — which was born in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. The exhibition explores the relationship between the American soul music of James Brown and the demands of the Afro-Brazilian movement in the 1970s.

Rio funk — often mistakenly considered to be the preferred music of gangsters — has been triumphing for years in the peripheries of Brazil. Little by little, it’s finally acquiring the status of a respectable cultural expression, a path that samba already followed decades ago.

In the two rooms of the MAR that are hosting the exhibition, which runs until August 2024, the sound is thunderous. Visitors who have never been to one of these massive dances — which are held outdoors at dawn under plastic tarps in peripheral Brazilian neighborhoods — feel as if they’re standing next to a wall erected with speakers, which hammer out the funk. This is the same rhythm that catapulted Anitta, the great diva of Brazilian music, to international fame.

“I’ve come to see our history emblazoned in a museum,” explains Anna Luisa Lopes Jacinto. The 31-year-old makeup artist is excited and proud: she used to attend the dances in the municipality of Itaguaí, in the metropolitan area of Rio. She’s visiting the exhibition with a friend.

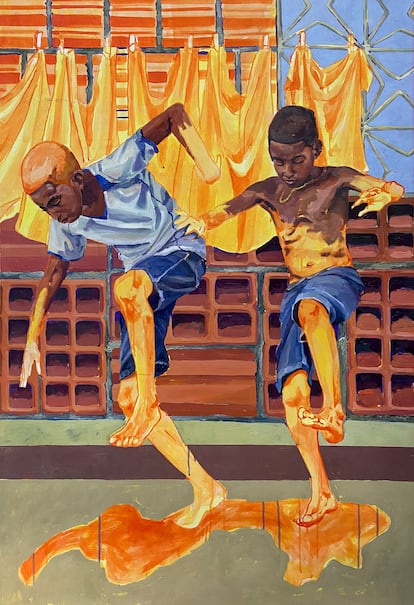

It’s essential not to confuse Brazilian funk with American funk, the latter of which was born in the U.S. in the 1960s out of rhythm & blues. The sound that emerged in the 1980s in the poorest neighborhoods of Rio, on the other hand, combines the rhythms of Miami bass with elements of electronic music. It also includes local folklore bequeathed by enslaved Africans, such as maculelé. The musical mixture is fast-paced, often with very explicit lyrics. In the museum, along with old photographs of the first dances organized by the Afro-Brazilian public, there are advertising posters and album covers on display, along with videos of the elaborate choreographies of today’s funk movement. There are also colorful, updated versions of the engravings that portrayed the life of slaves in Rio during the Portuguese colonial era.

“Funk is a scream — it’s not just music,” explains curator Marcelo Campos, in an interview at the MAR. “Always at full volume, at a level above what the residents and the city council find acceptable. It’s a bold cry, because it speaks about governance in the favelas, about the fights between men and women, about the empowerment of women, who speak badly about men.”

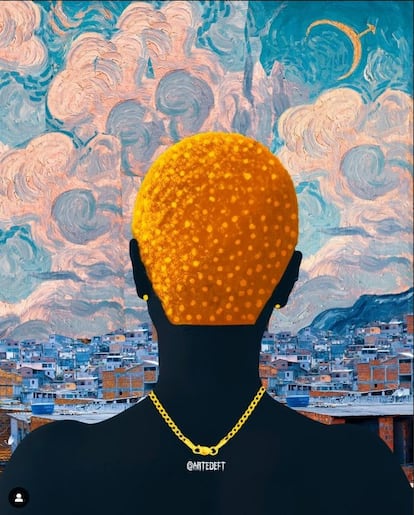

The stigmatization of funk is part of a pattern that has historically criminalized the entertainment of Black people. For centuries, millions of human beings of African descent were considered to be mere instruments of work. Hence, there’s extraordinary symbolic power in the soled shoes worn during the first dances organized by Black Brazilians. As one of the explanatory panels in the exhibition details, footwear was part of the proud response of the descendants of slaves, who were prohibited from wearing shoes.

Campos highlights that, today, “funk experiences the same marginalization that samba once suffered from. The police also persecuted rodas (samba sessions) in the early 20th century. Everything that is said today about funk was also said about samba. That [those who danced to it] were somehow criminals. Samba also had its governance, its bad guys, its knife-makers.”

The shantytowns invented dances, because in those labyrinthine alleys, there’s some fun to be found… while the state is neither present, nor expected. The authorities have viewed these self-organized events with suspicion, or have even persecuted them because they were held without a permit. One of the frequent accusations made by the security forces or municipal governments is that the events are financed by the drug traffickers, who dominate many favelas. It’s not unusual for the dances to become targets of police operations. From time to time, members of the security forces film traffickers, who are armed with automatic rifles as they make their way through the dancing crowds.

In 2019, officers were deployed to arrest two suspects who were accused of opening fire on police. This led to a raid on a crowded dance hall in a São Paulo favela, which ultimately left nine children dead.

Marcos Reis, 25, says he was 16 when he went to his first funk dance. The cashier emphasizes that he attended with his parents’ blessing. Such an event was deeply frowned-upon outside the favelas. “I’m from Senador Camará — a peaceful favela — and it was never taboo there. For me, it’s really important to be able to discover where funk came from,” he tells EL PAÍS, while touring the museum.

Campos explains that Funk: A Cry of Boldness and Freedom raises its own theory about the origins of Rio funk. “Our hypothesis is that it was born from the Black soul movements… a connection that isn’t usually made. Funk is very popular, but it’s not usually associated with what we today call racial literacy, with political discourse. James Brown brought racially conscious songs to Rio.” Those who live on the other side of the tunnel — far from the glamor of Copacabana and the other beaches that tourists visit — adapted these songs to make their own rhythm.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.