The long road home for a stolen Hernán Cortés manuscript

In an exclusive for EL PAÍS, the FBI details how it recovered a nearly 500-year-old document, which will return to Mexico this month after its disappearance three decades ago

From Mexico City to the Museum of World Treasures in Wichita (Kansas), from an auction house in Los Angeles to a warehouse in New Hampshire and from the FBI offices in Boston soon to return to the Mexican capital. Such has been the long pilgrimage of a manuscript written by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés dating from 1527 that was stolen from the General Archive of the Latin American country in the early 1990s. It is scheduled to return home later this month, following intervention by authorities on both sides of the border, analysis by specialists in ancient documents, and an in extremis civil forfeiture action that prevented the piece of paper from changing hands again. “Antiquities theft and trafficking is a worldwide problem,” says Agent Kristin Koch, in the first interview the FBI gives on the case. “Criminals will always find a market and sell anything they can get their hands on,” she adds.

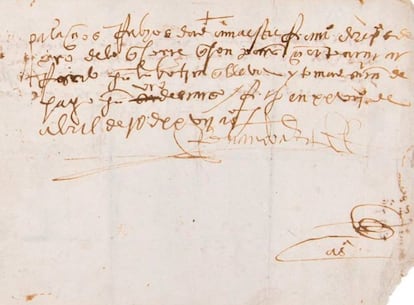

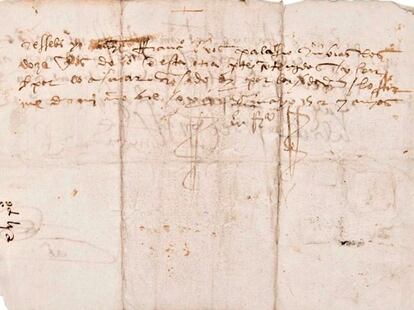

The document measures just 21.5 by 15 centimeters (8.4 by 6 inches) It is a payment order given by Hernán Cortés to his steward, Nicolás de Palacios Rubios, to buy the equivalent of 12 gold pesos of “pink sugar,” possibly during an expedition in the current territory of Honduras. On the front are the purchase instructions in old Spanish and on the back, the confirmation from the owner of an apothecary’s shop, Maestre Francisco, that he received payment.

“Ressebi yo maestre Francisco de vos Palaçios Rubios los doce pesos de oro en esta otra parte contenidas y son por el açucar rosado oy por bos dado, lo firme de mi nombre, oy 13 de mayo 1527 años” [I, Maestre Francisco, received from you, Palacios Rubios, the twelve gold pesos herewith contained for pink sugar given today, signed by my name, today 13 May 1527], it reads on the back. The document, in iron gall ink on cotton paper, vanished without a trace from the General Archive of Mexico and workers became aware of the theft when they were backing up the file it was part of on microfilm. This made it possible to determine the approximate date of the theft: October 1993 or earlier.

Finding out the fate of the manuscript seemed as complicated as looking for a needle in a haystack. There were no clues until decades later. At the end of May last year, a researcher alerted the head of the Archive that he had seen an object at auction that had caught his attention. The order from management was to recover the document at any cost. Mexican workers told EL PAÍS that it was a race against time because the auction was closing on June 15, 2022. “Incredibly rare money order to buy pink sugar, signed by the conquistador Cortes,” stated Boston auction house RR Auction. A week before it ended, the manuscript had already received 22 bids and the bid price was over US$18,600 (€16,548).

The Archivo General de México team telephoned an FBI tip line on June 6, 2022, ten days before the auction ended. “We receive hundreds of reports every day,” Koch explains. The legal attaché of the U.S. Embassy channeled the call to the Art and Crime Unit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, a specialized group in charge of investigating crimes such as museum theft, heritage trafficking, and counterfeiting of cultural property. “The Mexican authorities called us back with more information about the document and their reasons for believing it was the manuscript that had been stolen, and thanks to that, we were able to open an investigation,” adds the agent, who has almost 20 years of experience in the unit.

After initiating inquiries, Koch contacted the auctioneer, who agreed to remove the item from the website until the situation was clarified. Information from Mexico enabled them to obtain a seizure warrant and U.S. agents began to investigate the manuscript. “We wanted to know how this document had ended up in the United States,” Koch notes.

But it was like putting a jigsaw puzzle together, because so much time had passed since the theft and there was little documentation in the hands of the auctioneers who had held it for years. “In these types of cases, tracing the provenance of the items becomes very challenging, because as more time passes, it becomes more difficult to find people who have good records on the objects and who keep them,” he adds.

The FBI limited its comments on the specifics of the case, but court documents held by this newspaper shed light on what happened to the manuscript during the 30 years it was off the radar. After the paper was torn from a documentary collection at the General Archive of Mexico, a person identified by the initials J. K. bought it at auction in the United States in the early 1990s. J. K. added it to his private collection and loaned it to the Museum of World Treasures in Wichita (Kansas), which he had founded. It was exhibited for 20 years in the city.

After the death of the new owner, his family gave the item on consignment and it was auctioned again in Los Angeles by Goldberg Coins and Collectibles, where it was acquired in 2019 by another person, identified as R. N. The buyer took it home to Florida and it was he who delivered the note to RR Auction, the Massachusetts-based auction house last year. The document was moved to a warehouse in New Hampshire until it could be sold to the highest bidder.

Before that, the payment order and other archives remained stored for four centuries in the Hospital de Jesús, the oldest in the Americas and founded by Cortés himself on 20th November Avenue in Mexico City, in the same place where it is believed that the Spanish conquistador first met with the tlatoani [ruler] Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, in 1519. In 1929, all the documents found at the site were declared heritage of the Mexican state. “Typically, what I’ve seen happen with works of art or antiques is that they can pass through many hands over the years after being stolen and many times this happens because they are traded in private sales. These are often not advertised on the internet, meaning that the transactions are not visible to the authorities or the general public,” Koch comments.

“Usually, people are surprised when they find out that the items they have are stolen and many times, when they realize the cultural value they have for the countries of origin or the original owners, they are willing to part with the object and give up fighting to keep it,” the agent points out. When there is sufficient reason to believe that the object was stolen, the authorities first try to make the return or the decision not to auction it a voluntary one.

This was the case with the Cortés manuscript, which was removed from the catalog before there was a court order. “They are not usually happy about losing money, but they are willing to let these documents go back where they really belong,” Koch adds. The authentication of the document included scientific tests and the joint work of experts, officials, police officers and diplomats to overcome the repatriation procedures.

“What was great about this case was the cooperation between the U.S. and Mexican governments in giving us all the information so that we could act, and the case had a positive outcome,” says Koch. After several months of waiting, the manuscript is scheduled to be delivered at a ceremony in Mexico City, pending the official announcement.

“We are constantly receiving leads and tips on stolen cultural heritage from all over the world, including Mexico,” says the agent, who hopes the case will lead to further investigations and efforts to return more treasures to their original owners. The Latin American country has successfully repatriated more than 11,500 objects of historical value in the last five years, including 16 court documents that were to be auctioned in New York and were returned last year.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.