‘They’re gamblers at an emotional casino in their minds’: Why the rich pay for risky experiences

The wealthiest 1%’s taste for risky activities, such as the ill-fated submarine trip to the ruins of the ‘Titanic’ has, among other things, a physiological reason. The class barrier is not only in luxury

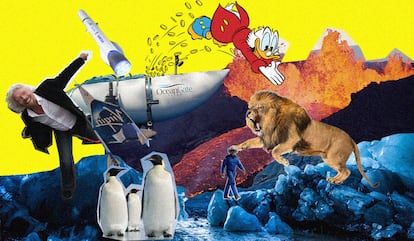

The tragedy of the Titan, a now-infamous submersible, has brought up a curious question: how do billionaires, that narrow elite of pharaohs of opulence who can buy virtually anything, spend their time?

We are talking about human beings who accumulate limited editions of Ferrari or Rolls-Royce in their garages. They collect art, of course, from Cézanne to Da Vinci through De Kooning, Picasso, Warhol, Modigliani, Koons and Gauguin. They sleep in beds with canopies of ash, chestnut, sapphires and diamonds. They collect private islets and jets with platinum fuselage. They tour the world aboard gold-plated yachts. They eat Piedmontese white truffles, royal oysters from Australia’s Coffin Bay and Almas beluga caviar. They drink vintage Bordeaux reds from Thomas Jefferson’s cellar and Henri IV Dudognon cognac from 24-carat gold bottles. They wear €20 million euro watches and use cell phones that cost €48 million.

But even those signs of economic splendor are trivial if we compare them with genuinely exclusive experiences, like the still-nascent space tourism and luxury submersible expeditions to the Marianas Trench. In a sense, the sinking of the Titan has exposed an uncomfortable truth: the closets of opulence are full of pioneering billionaires, adrenaline junkies who are eager to risk their lives.

The luxury of life

For adventurers of the lineage of Elon Musk or Richard Branson, true luxury consists in “feeling alive,” at least according to Scott Lyons, a British psychologist who has among his clientele some of the largest fortunes on the planet. Lyons assures that the attendees of his therapy “practice extreme sports such as skydiving in the peaks of the Himalayas, crossing deserts and tropical jungles and diving to depths that test their lungs’ capacity, as antidotes to boredom and existential weariness.”

Among billionaires, according to the therapist, “compulsive personalities, prone to boredom and with a tendency to explore their own limits” abound. Ambrose Bierce said that most of the human beings we call “heroes” actually suffer from “a socially accepted form of narcissism or stupidity,” while so-called “cowards” are people who have not yet lost their self-preservation instinct.

In the ill-fated story of the Titan there is a would-be hero, Hamish Harding, who died aboard the vessel after spending a lifetime becoming filthy rich, participating in various recreational expeditions to Antarctica, enlisting in journeys beyond the atmosphere and breaking several Guinness records. The saga also includes an alleged coward, Chris Brown (not to be confused with the singer), who listened to his self-preservation instinct and stayed on the ground.

Harding and Brown both enlisted in the exclusive crew of Stockton Rush, uncrowned king of luxury submersibles. Both had the opportunity to inspect the ship on a trip to the Bahamas and agreed that it was a “precarious-looking” submersible, which used “scaffolding poles as ballast” and was operated with a wireless control that looked like the toy joystick of a video game console. Brown stepped aside and demanded the return of the $25,000 deposit (one-tenth of the price of the voyage) that he had already paid. Harding, despite everything, decided to embark.

Blame it on the amygdala

Lyons attributes decisions like Harding’s to a “powerful psychological mechanism very common in successful people,” which is activated in the amygdala, an almond-shaped nuclear mass located deep in the brain’s temporal lobes. In this center of instant gratification, Lyons explains, “risky situations are processed, and that generates a cascade of hormones, such as dopamine, testosterone, norepinephrine, adrenaline and serotonin.”

People accustomed to dealing with these “hormonal earthquakes” can end up developing an addiction “to the feeling of power and the momentary relief of the pain and apathy that they generate.” As with other psychoactive substances, in the medium term, to continue obtaining the pleasant sensation, it is necessary to gradually increase the dose. The slaves of the amygdala willingly enter “the spiral of risk” and seek increasingly intense and extreme experiences. If you’ve already orbited the planet like Yuri Gagarin, what’s next?

Lyons adds that “the pleasure of this exponential risk-taking is very similar to that associated with winning large amounts of money.” In other words, the millionaires who travel the African continent in hot air balloons making a stopover to look for the proximity of lions, elephants and rhinos in the Masai reserves could be described, in some cases, as “gamblers in an emotional casino located in their own brains.”

Caitlin Tilley, writer for The Daily Mail, identifies other examples of the gambling for extreme experiences, starting with the space flights of Virgin Galactic Holdings, the Branson company, and the alternatives offered by its competitors, Bezos and Musk. Branson has tried to “democratize” tourism in the stratosphere to a certain extent “offering experiences lasting around 90 minutes at a price of between €250,000 and €400,000, which has led him to take more than 800 reservations.”

Blue Origin, Bezos’s company, “sold its first ticket for about €25 million and today offers (brief) weightlessness experiences 350 kilometers from the earth’s surface.” And the Starship, Musk’s rocket made by his company SpaceX, “has sold out the entire capacity of its next trip to the Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawua, who is looking for companions for the circular journey around the Moon scheduled for the end of this year.”

Alpine skiing at the summit

Tilley also highlights “the very exclusive practice of alpine skiing on the slopes of the Himalayas, which is accessed by helicopter,” an activity that has not been interrupted “even in the phases in which the area, on the border between the Indian Union and Pakistan has become the scene of clashes between the Indian army and Kashmiri Muslim separatists.” On the contrary, the proximity of that other kind of danger makes it even more interesting. Safety is also at risk for those who fly by helicopter to the top of Mount Roraima, between Brazil and Venezuela, the place where Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel The Lost World takes place. The passengers descend from there to the ancient reservations of the Pemón indigenous people.

The epitome of kamikaze tourism may be trips to some of the most troubled, unstructured and hermetic countries on the planet, such as Afghanistan, Yemen, Turkmenistan, Syria, Somalia and the mecca of those nostalgic for the Cold War, North Korea. The last of these destinations plans to keep its borders closed during 2023. This will prevent events as tragic as the one suffered in 2016 by the American university student Otto Warmbier, arrested at the Pyongyang airport minutes before the flight that was to take him back home departed. Warmbier had tried to take as a souvenir a propaganda poster that caught his eye at the hotel where he was staying. After the arrest, he suffered torture, was prosecuted for “subversion” and was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. In June 2017, he was returned to his country in a vegetative state. He passed away shortly after. Warmbier was not a billionaire eager for extreme experiences, but his self-preservation instinct was not in action.

Joan Miquel Gomis, professor of Economics and Business at the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, recalls that tourism “had always been an exclusive activity, restricted to a certain elite, until its democratization in Western societies,” a phenomenon that has occurred “in recent decades.” Globalization has accelerated this process to a point where “it is difficult to find corners of the planet that do not receive a constant flow of tourists.”

As the main destinations have become overcrowded, the elites have developed a thirst for exclusive experiences that is increasingly difficult to quench. Even “the last redoubt of exclusivity, space travel, looks to become popular in order to be profitable in the medium term.” Without leaving Earth, “it is previously hermetic countries, such as Qatar or Saudi Arabia, which are consolidating increasingly ambitious tourist infrastructures and oriented, for the moment, toward luxury visitors.” But even in these destinations of emerging opulence, “the exclusive model coexists with the most common, not restricted to the elites.”

For Gomis, if the super-rich who love to travel have something in common, it is “they reject standardized circuits.” Consequently, they fly in “private planes, stay in exclusive villas and rent islets.” Their individual habits may depend on personal variables: “A fan of motorsports, in addition to accumulating luxury prototypes, will attend events such as Formula 1. Others specialize in arctic missions or in unique gastronomic experiences, always guided by very selective criteria.” There is, of course, a whole commercial warp of companies determined to satisfy these preferences, “which very often take the form of eccentricities or whims.”

Asturian businessman Gonzalo Gimeno, general director of the “tailor-made” tourism company Elefant Travel, offers a different perspective. Gimeno is not interested in adrenaline junkies, but in a customer profile “who appreciates true exclusivity and is willing to pay what it’s worth.”

The trips that Elefant organizes are not, in the words of its top manager, “neither retail tourism nor boutique experiences, but tailor-made suits.” To this luxury “tailor,” who works above all for “senior managers of IBEX 35 companies, great fortunes and elite athletes” from his company headquarters in Madrid, Barcelona and Medellín, the secret formula consists of “having a team of professionals who travel more than 300 days a year, which has allowed us to achieve exhaustive knowledge of potential destinations and consolidate a wide network of collaborators, whom we call correspondents.”

What kind of experiences does Elefant offer? For example, “spend a few hours participating in the task of restoring mummies in the Egyptian necropolis of Saqqara.” Or “having a six-room cabin in El Chaltén, in the Argentine Andes, with a splendid glacier all to yourself.” And “à la carte trips through British Columbia that include private villas with a helipad, swimming pools and wooden chalets, but also austere tours through the forests or descents into the spectacular ice caves, as well as black bear watching routes.”

For those who want to access Antarctica, “an inhospitable environment where the activities that a normal person can carry out are very limited,” Elefant suggests “alternatives such as a boat trip from Puerto Montt, in the south of Chile, and a visit to the Chilean Antarctic base completed by some hiking and boat excursions.” To those who have suffered “massive African safaris without the slightest charm by the most conventional tour operators” he proposes “Laikipia, in Kenya, the preferred destination for exclusive safaris, or Botswana, where you can also enjoy such dynamic activities like kayaking downhill.”

Luxury is a row of cypresses

Elefant offers elite soccer players, its most “peculiar” users, “privacy and tranquility, which for them constitutes true luxury.” The last such client spent “15 days in a villa where we had an elite training gym transferred by ferry, and we planted a row of 15 cypress trees so that the paparazzi could not photograph them from the sea.” Another athlete was given “exclusive access to a glacier in the heart of Iceland and a romantic dinner with his partner, by torchlight, inside a tunnel of volcanic lava.”

Gimeno adds that the type of experience seeker that Elefant thrives on requires, first of all, private (or, at least, privileged) access to unique spaces. Hence the popularity of options such as “the rental of temples such as those of Angkor, in Cambodia, or Luxor, in Egypt.” The fundamental thing, in Gimeno’s opinion, is “listening to the customer, understanding their expectations and tastes and ending up offering them not a destination, but a personal and non-transferable travel experience.” Not all tourists with a high net worth are looking for the opportunity to risk their integrity in extreme activities. Some enjoy their money by keeping the amygdala safe.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.