Joséphine Baker’s son: ‘For us, her most obvious legacy is tolerance’

Jean-Claude Bouillon-Baker, one of the 12 adopted children of the iconic dancer and activist, remembers his mother following the publication of a graphic novel about her life

In the Lovo Bar, located in the heart of Madrid’s downtown Barrio de las Letras, the essence of Joséphine Baker is everywhere. There are photographs of her on the walls, as well as cocktails inspired by her life. The dancer, actress and activist is an essential part of the “roaring twenties” atmosphere.

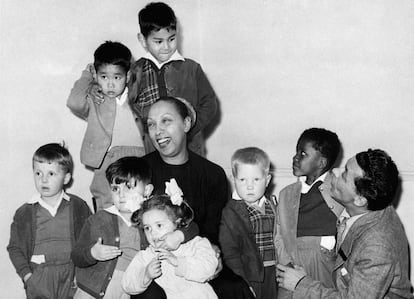

Jean-Claude Bouillon-Baker pauses to look at a photo of his mother that is displayed along the stairwell. The 68-year-old man – the fifth of the 12 children adopted by Joséphine Baker and her husband, Joe Bouillon – spoke to EL PAÍS about the graphic novel Joséphine Baker, which is based on his mother’s life.

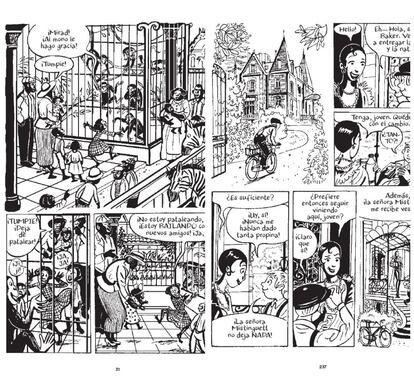

The comic book, illustrated by Catel Muller and written by José-Louis Bocquet, is an illustrated biography that traces the unusual path of the Missouri-born French icon, who was the first Black woman to star in a major motion picture. The fast pace of the comic is necessary to cover the sheer vastness of her life experiences.

Jean-Claude promoted this project: “I wanted to bring the story of [my mother’s] life to the youngest readers. To do this, I was looking for a more playful genre. I thought of comics and contacted Muller and Bocquet in 2013.”

Joséphine Baker, who passed away in 1975, is a fixture in French schools and creative institutes. Now the book is also being discussed by teachers and students.

Less than a year ago, on November 30, 2021, Baker’s remains were transferred to the Panthéon, a striking neoclassical structure in the 5th arrondissement of Paris. It acts as a mausoleum for the most distinguished French citizens. The date coincided with the anniversary of her obtaining French nationality: she received it upon marrying Jean Lion, the third of her four husbands, in 1937.

For her son, the fact that she was the first Black woman to be entombed in the emblematic monument in the French capital is extraordinary. “More than a thousand people attended the ceremony. I was very surprised to see Marine Le Pen [the leader of the far-right National Front party], but her presence also made me happy: it showed how much my mother was an established icon for all French people.”

In the Panthéon, Baker is surrounded by writers such as Victor Hugo, Émile Zola and Maurice Genevoix. This stirs immense pride in Jean-Claude, as he is the author of several books.

When Joséphine crossed the Atlantic in 1925 at the age of 19, France offered what the United States had always denied her: being a citizen with full rights.

“When she arrived in Paris, she left hell to enter paradise. On the first day of World War II, she said: ‘France has made me what I am and can ask me for anything it wants.’ She even offered to join the French secret service to be a spy against the Nazis… she wanted to use her popularity to sneak into embassies, transcribe secret messages on sheet music,” Jean-Claude explains. His mother even Francized her name, adding an accent to the “e” in Joséphine. She corrected anyone who pronounced her surname in English: “It’s Bah-ker, not Bei-ker!”

Although she never told her adopted children about the misery she suffered during the era of segregation in the United States – nor about her role as a spy in the Resistance during Nazi Germany’s occupation of France – they soon learned on their own.

Her son remembers when two helicopters landed in front of the Château des Milandes, where the family lived. Military officers had arrived to present Baker with the Légion d’honneur on behalf of General Charles de Gaulle.

On that vast piece of land in the south of France, Joséphine and her fourth husband raised 12 children of differing backgrounds. Many of them had been made orphans by World War II. There were two children from Japan, one from Finland, one from Colombia… Jean-Claude was of French descent.

This excerpt of an interview with Jean-Claude Bouillon-Baker has been translated and edited for clarity.

Question. What was Joséphine like as a mother?

Answer. Very loving. She loved children and animals. She had immeasurable love to give, because she couldn’t have children of her own. Sometimes she could get serious, though, because she was afraid that, as we grew older, we wouldn’t be kind to each other.

I remember once, when we were little, while we were eating together at the kitchen table, I made a comment to my brother Akio about his country of origin to piss him off. He started crying. My mother found out what I had done. She used a poker to give me a good blow on my back! But she wasn’t violent, she was just always afraid that we would be intolerant.

Q. Did you get the message?

A. Of course! It was a success. And all of us keep in touch. Last Sunday, I met with two of my brothers to inaugurate some social housing in our mother’s honor. For us, her most obvious legacy is tolerance.

Q. What was life like at home?

A. Well, whenever she would appear on TV, singing, half-naked, she would turn it off very quickly and tell us that “it wasn’t her.” Because she wanted us to see her as our mother… not as a dancer. There was no talk of music, dancing or singing in the house.

Q. Can you think of a moment with her that marked you significantly?

A. Something that stands out is the moment I understood that she was an artist. I was nine years old in a Swiss boarding school, more than 600 miles from home, and I was very unhappy. So, I decided to pull a prank that would get me kicked out. I knew that my mother was on tour in Zurich at the time... I stole a chocolate bar from my roommate’s cupboard and purposefully allowed myself to be caught.

I was worried all day without knowing how she would react. In the evening, I watched her arrive at the hotel, surrounded by a cloud of journalists. She saw me waiting and took me in her arms. We never talked about the incident again.

That same night, she told me to go see her performance. I was sitting at the back of the theater when she appeared on stage: the whole audience stood to cheer. They adored her, they admired her. I said to myself: “Now I understand who my mother is.”

Perhaps what my siblings and I lacked the most was having moments alone with her, for her to love us a little more individually.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.