An hour with Mick Jagger at the Reina Sofía

Ángeles González-Sinde, the president of the museum’s Royal Board of Trustees, recounts the Rolling Stones star’s visit one day before his concert in the Spanish capital

We were notified the day before. He was tired, he had returned from Valencia, he had had two meetings and he would still have time to wait until the visit. I thought about going home. I’ve seen many celebrities from afar, after all, but then I told myself, if only to tell my friends, I’m staying. We went down to the loading and unloading area, where the boxes with the works of art come and go. His head of security arrived first, in a Maserati. I pointed it out to the director of the museum: “Look, Manolo, a Maserati.” He has no idea about cars, and he asked me with an amazed, boyish expression, “Is that a good car?” “It’s a very expensive car,” I answered, calculating, “€200,000, plus insurance.” (When we see an expensive car, middle-class people always think about insurance.) “The artwork we could buy with that,” we both sighed.

The reception committee consisted of Manolo, me, the deputy director of the museum, the chief of staff, the head of security and Madrid’s director of culture, who had arranged the visit. The man from the Maserati, a hefty Italian with square shoulders and an attitude, wanted to see the entrances and exits. We showed him around, and he took photos that he sent to other bodyguards. We waited and waited. Someone commented that the Italian had been a mercenary in some wars. We looked at him askance. He frightened us even more, although his tattoos seemed more like they came from a club than a war. We kept waiting. They were late. We didn’t know exactly who would come. The Stones in general. The wait sent me back three decades, when I worked as a performer and transportation coordinator for the artists that the music promoter Gay Mercader used to bring over to play concerts in Spain [including the first Rolling Stones concert in this country in July 1976]. I remembered the stress in airports, in hotels, in stadiums, doing exactly that: waiting for the musicians and shepherding them, behaving like an 18-year-old mother to gentlemen my father’s age, praying that the musicians and the chauffeurs would all arrive on time. That was in the mid-1980s, more or less when the Reina Sofía Museum which now housed us, was founded.

Finally, a black Mercedes arrived. It stopped, and a bodyguard ceremoniously opened the door. Ronnie Wood got out with his wife. We took them to the second floor. He looked at Guernica. Everyone wants to see Guernica, just like all of us wanted to see the Stones up close. He took out his cellphone, a small and simple model, and took lots of photos of the images of Picasso’s studio. I remembered that Wood paints. I mentioned it to him. “You are an artist yourself.” He was proud, and he showed us his paintings on his phone, including his own version of Guernica. Everything interested Wood. He asked questions. He was kind and cheerful. The director showed him other rooms, including Miró and Dalí. Then we were warned that another Stone was coming. I rushed down the stairs, back to the hangar. Wood mentioned that his twins were waiting at the hotel. “Family dinner,” he said, and left. Back on the dock, I started to get nervous. I had gone back in time again. I was 13 years old, writing in my diary: “Mick Jagger is the most handsome man alive. Mick Jagger is hot.” When I should have been studying, I spent hours listening to his records and looking at his photos. I would go to the movie studios to see the reruns of Performance, the Nicolas Roeg film that Jagger shot in 1970. I would leave the filthy neighborhood cinema with that intoxicating sensation of beauty and platonic infatuation, the awakening of that frightening erotic desire that is safe because it is attainable.

Another black Mercedes pulled up. A typically brusque bodyguard-butler-assistant jumped out, agile as a jaguar, but left the door ajar. The passenger was not ready to exit. We, the museum crew, ready to say hello, froze for moments of uncertainty, my slow 57-year-old heart beating as if it were 13. At last the door opened. He stepped out with his smile and his unmistakable haircut. The bodyguard-butler scolded us for not wearing masks. Hee strictly forbade accompanying him without one. I apologized and said I’d stay outside. My sad face moved the man, and he produced a mask out of nowhere. Now masked, we got in the freight elevator. The director, with his indefatigable enthusiasm, explained to Jagger the Civil War, the avant-garde movements, the universal exhibition of 1937, the Spanish Republic. I stayed in the background, but at one point, Jagger looked at me and started talking about a book he was reading, an essay on contemporary art and whether it should have political relevance or go back to being art for art’s sake. I asked him about the author. He couldn’t remember because he reads on his Kindle and, as happens to all of us, he doesn’t see the cover. “On tour you can’t carry books.” He looked at the works in the rooms with curiosity, in no hurry to finish the visit.

In a hallway I asked him about the concert the next day. “It sold out in minutes,” I said, referring to the cheap tickets, without adding that I knew firsthand because I was one of the thousands who had lined up virtually and was left without tickets. He replied, “in a stadium there is always room for more people,” with a mischievous smile. I smiled and kept quiet, while he explained that the Madrid concert was the first of the European tour and that the first concert is very important because–I dared to complete his sentence–”it sets the tone.” “Exactly, it sets the tone,” he replied. We moved through the rooms, but there were already fewer of us because the rough butler had expelled three of our colleagues. “Too many people, too close.” Although we were in our own house, we complied. Manolo, the director, improvised, and after Guernica, he decided to take him to see Cubism. First, though, he showed him Ángeles Santos’ “A World” and a Ponce de León piece that had decorated a movie theater. “Ah, cinemas,” he said, “used to be as sumptuous as palaces.” He seemed comfortable among the paintings and sculptures. Halfway through the visit, he asked us if it was our day off, because the museum was closed. He apologized for keeping us at dinner time. We lied, of course, and told him that we were there not because of him, but because we were working.

We went through the late 19th-century halls. He stared at the projection of the Lumière factory, and he told us that as a child he liked to watch people leave the factories. We agreed that the movement of crowds has something theatrical about it. In the same room we showed him the photos of trades, the primitive photographer’s attempt to portray the working class. He recalled how in his childhood each street vendor, like the woman who sold lavender, had a characteristic call. He seemed to enjoy talking about that remote world. He told us about a Francis Bacon exhibition he saw in London at the Royal Academy and another one on Futurism in New York. He was interested in the poster for Jack Johnson’s fight against Arthur Cravan. He told us that he had just seen a very good documentary about Muhammad Ali by Ken Burns, that he is a classic, old-fashioned documentary filmmaker, but that the documentary is fantastic and that Muhammad Ali used Jack Johnson’s scream for his fights because Jack Johnson had suffered a lot of discrimination. He laughed when he saw that the poster said “Jack Johnson black 100 kilos Arthur Cravan white 101 kilos,” as if the skin of each one had to be explained to the Spaniards of 1916.

He remembered the first concert in Spain in 1976 in Barcelona, six months after Franco died. He remembered the people and the excitement. He knew that some of his covers and records had been censored. It was similar when they first played in the East after the fall of the Soviet Union, he said. I wanted to ask him about the concert in Havana, but I was in a hurry. When we entered George Grosz’s room, he said that he had had one of the artist’s pieces, but that an ex-girlfriend took it from his house. Where is that drawing now? he wondered. He knew about the Commune of Paris and he was interested in what we told him, but I wasn’t able to explain much. It was hard for me to talk to him. I looked at his pale blue-green eyes; I listened to that voice that I had heard so many times on the records speak to me now with sweetness, with sympathy. Later that night, when I spoke with my friend Raquel, with whom I had shared my adoration for him, she told me, “he is a seducer.” It’s true, but how could I have imagined, in my blue-curtained childhood bedroom, that one day I would get what I wanted so much? She and I were transported back there, reading together the biography that recounted his infatuation with Marianne Faithfull, an ugly duckling who at 15 turned beautiful overnight. Why wouldn’t that happen to me? I wondered, feeling that if I were only beautiful, things would be better, because everything would be possible.

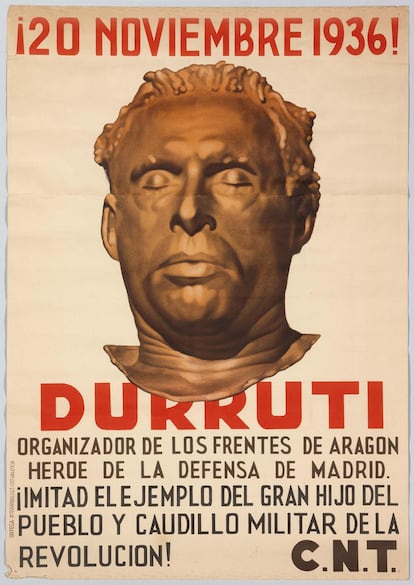

But we were not in 1978. We were in 2022, and I was 57 years old, which I forgot when Mick Jagger spoke to me. I listened to him smiling, happy behind my mask, not daring to tell him anything I was thinking, not even explaining who Durruti was when he looked curiously at the poster of his death mask and the images of his massive funeral. I remembered other matters that linked me to him, those choruses I sang in playback when I was on a TV show for Bill Wyman at 16 years old: “Come back Suzanne, come back Suzanna, baby baby please come back.” I didn’t say a word about myself, as if the conversation weren’t a conversation, just a way to pay a debt, a tribute for the times he made me feel good. Does Mick Jagger, the person, also feel that he is not perceived as an individual, but as a container of dreams? Does he know that he is seen only as a mirror that reflects an image of ourselves in another time? Is he resigned to being erased by his excessive exposure, by the wear and tear of a constant connection with the intimacy and the unconscious of others? Or does he still aspire to be a person, not an atmospheric phenomenon hopelessly seen from afar like the yellow moon on a summer night? I looked at him and listened to him, and I knew that he was not a long-lost beloved family member with whom I had finally reunited, but rather a vessel of fine porcelain–a vessel where the rest of us deposit our desires and thoughts. Does he regret that he is rarely seen for what he really is?

As I walked parallel to him, I looked at his skin, his blond eyelashes, his lips. I told myself, “he’s an English gentleman, like so many others.” But this English gentleman had the eyes and the smile of that other time, just as I had suddenly become a girl who discovered that men were beautiful and had something that made one want to be close to them. Very close. Forty-odd years later, walking through the halls of a museum, everything that had happened between 1978 and an afternoon in May 2022 had ceased to matter. It no longer existed. All the deaths, the absences, the disappointments, the violence suffered, the sadness, the wrong decisions, the damage done and received, the mistakes, the boredom, were erased. The minutes with Mick Jagger seemed to belong just to the two of us, to the strange intimacy between his music, his youthful portraits pasted on my notebooks and my distant memories, now so alive, so fresh, of being 13 years old, before anything has happened, before being kissed, before leaving home and school.

On the way out, as we crossed the cloister and left Man Ray’s metronome behind, he told me that once he called Man Ray on the phone to ask him to do a record cover. The artist was already a very old man, and there was no way to convince him. Since he was in no hurry to leave, because he likes art and chatting about it, he couldn’t resist the temptation to go into Picasso’s Lady in Blue room. On the other side of the wall, there was a group on a private visit, but he was not in the least disturbed. He listened calmly to Manolo’s explanation about the portrait of a prostitute. He wanted to take a photo. Manolo watched the group and whispered to me, “if they knew who is on the other side of the partition…” But they were focused on their own guide, and who is going to suspect that Mick Jagger is two meters from you? We got to the elevator. While we waited, he placed his foot on a railing and reached down to tie his shoelaces. The colored socks looked good on him, as did the electric blue pants and the shirt with little printed figures, open over a T-shirt of the best cotton. I looked at him again. Yes, it was him. It was Mick Jagger.

Everything had started again: the pure, sweet joy of innocence had returned.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.