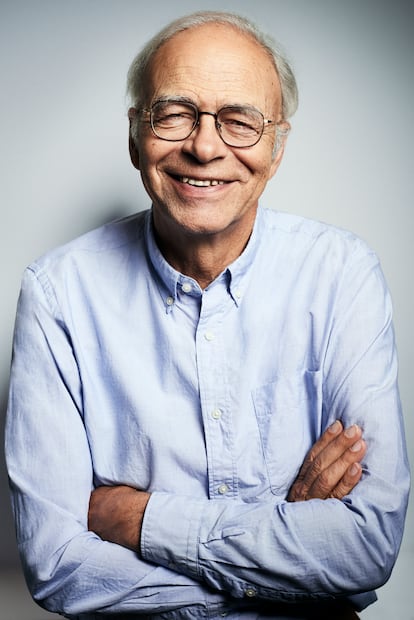

Peter Singer: ‘Consciousness isn’t exclusive to humans, or even to primates’

Half a century ago, the Australian thinker was known as the radical philosopher of animal liberation. Now, his theories have changed legislation around the world, and he is publishing two new books in Spanish

Peter Singer is the man who has convinced half the planet that animals feel pain, the philosopher that has pushed parliaments to legislate on animal well-being, the bioethicist that has become a referent for moral questions across the globe. He has defended euthanasia for cases of children born with deformities and unbearable pain, despite how unpopular his views may be to the casual observer or provocative pundit.

Singer, born in Melbourne, Australia, is an ethical and political philosopher whose work covers a broad spectrum of topics. The 75-year-old is best known as one of the founders of the animal rights movement. But he is far from a small-minded activist concerned more for animals’ well-being than for his fellow humans. His wide-ranging intellect, and his personal history, do not allow such narrowness.

The son of Viennan Jews who escaped to Australia in 1938, Singer grew up in a family living in the shadow of the Holocaust. Three of his four grandparents died in Nazi concentration camps shortly after his parents left Europe. His animalism is a genuine intellectual posture, not the whim of a citizen bored by other people. His book Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for our Treatment of Animals, published in English in 1975, catapulted him to philosophical stardom. He has taught bioethics at Princeton University for 23 years, and he has just published a Spanish-language adaptation of The Golden Ass, a book by second-century Roman philosopher Apuleius, who shared Singer’s profound empathy for animals. Soon to be published in Spanish is also Singer’s The Great Ape Project.

I spoke with Singer over a video call about the latest advances in the neuroscience of consciousness. Recent discoveries demonstrate that the quality that we believed to be exclusive to humans is located not in the front of the brain, the part that has developed the most during human evolution, but in the areas that we share with animals. On whether he sees the discovery as a confirmation of his theories, he says, “yes, I think that consciousness goes very far back in Earth’s evolutionary history. Its presence has been confirmed in other mammals, and I think in all vertebrates, including fish, and even in certain invertebrates. We have all now seen the famous documentary about the octopus, My Octopus Teacher, which demonstrated to people that octopuses are also conscious beings, even when their consciousness has evolved independently from ours. The evidence we are accumulating in neuroscience demonstrates that consciousness isn’t a phenomenon specific to humans, or even to primates, but it comes from much further back in evolution.”

The philosopher admits that the idea of our close affinity with the animal kingdom has pervaded scientific thinking since at least the 19th century. “Darwin recognized that we aren’t a separate creation, a very important point, because in religious texts, like for example the literal reading of Genesis, humans are a direct creation of God, the only ones made in his image and likeness, the only ones who possess an immortal soul that survives the body. Many people, including Aquinas, interpreted that as a denial that we have obligations to animals. We would only have them to other beings that have immortal souls, and that only leaves us, humans. But Darwin showed that that is a fallacy, because we are not made in the image of God, but rather we are products of evolution from other animals. That is Darwin’s fundamental perception. We aren’t masters of animals. We simply live on the same planet as they do, and we have no right to suppose that our pleasures and pains are unique or different from theirs. In fact, Hinduism and Buddhism don’t see as clear a division between humans and other animals as Christianity does.”

Some thinkers – perhaps the vast majority – do not accept that animals are capable of suffering. Singer has no patience for them. “In a philosophical sense, we can’t be certain that animals suffer and feel pain. Solipsism is a difficult position to refute. Because I suffer, I can be certain of my pain, but not of yours. Though this idea is hard to refute, it does not seem convincing to me. We see the same reactions to pain in animals as in humans, based on the same nerve phenomena. An aspirin or paracetamol relieves pain in both humans and animals. The proposal that they are not conscious of their suffering seems unlikely.”

Since Singer is a vegetarian, I ask him my favorite question for vegetarians: would you eat a hamburger made of stem cells? “I would eat a hamburger of stem cells if no animal had suffered in the process. I’m not vegetarian because I reject a type of cell, but because of the pain that obtaining them causes.”

One concern of scientists is that the animal movement can pose obstacles to experiments with lab animals, which today are essential for research on human health. Singer has a nuanced position: “I don’t share the idea of any animal group that believes that experimentation with animals is always unjustified. I am a consequentialist. I judge what is good or bad by its consequences. But when I examine experiments with animals, I find a great number that are not necessary for human health or survival, for cosmetics, for example, or to test food coloring.” Singer makes special reference to the animal tests that examine whether post-traumatic stress can be linked to suffering in childhood, inflicting suffering on animals to see whether it increases their likelihood of PTSD. “I think there are better ways to help people with post-traumatic stress.”

Singer is clear about his stance against bullfighting. “Bullfights can be considered the heirs of the games in classical Rome, where the beasts ate gladiators and Christians. It is incredible to me that the bullfights have survived until today, despite the public’s general rejection to entertainment being based on inflicting suffering on animals. It is a peculiar tradition, and there are so many other ways of having a party, with all those magnificent soccer teams you have in Spain and so many people who enjoy watching them, that I would recommend soccer before bullfights.”

I first interviewed Singer over 20 years ago. I remember that I arrived at our appointment ready for a fight, with provocative questions including, “humans have invented human rights, shouldn’t monkeys invent their own?” Not a minute of the interview went by before I realized how wrong I was. It was clear that Singer was a deep, reflective thinker, not the plant-eating bigmouth I had envisioned. Still, I decide to repeat one of the questions that I asked him then: should computers have human rights? “One day they should have them,” he responds, “but we aren’t any closer to that day than we were 20 years ago. Despite all the advances in artificial intelligence and computing in these 20 years, we still have yet to see perspectives from a conscious machine, one capable of suffering and enjoying life. True, 25 years ago we didn’t have a computer that beat the human chess champion, and now we do. They can even beat us in more complicated games like Go. There have been great advances, albeit in very limited contexts. But if we are looking for a general artificial intelligence, one that allows us to perceive a mind as flexible as ours, and capable of responding to the world as ours does, it does not yet exist. Ask me in another 20 years.” Both of us laugh at the possibility of that interview taking place: jokes of old men.

I ask him to pivot towards Ukraine: is there an ethics of war? “There are ethical rules of war, and if they were observed by all parties in a conflict, wars would probably be less atrocious than they are. There is an ethic of when to go to war and one about what to do once you have gone. But if the question refers to the present context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there is no justification for Russia going to war, and it has not respected ethical conduct of how to fight in a war.”

I ask him to compare this conflict with the Iraq war, which began with an allied invasion of the Middle Eastern country. “I was against the Iraq war at the time. I didn’t think it was justified, nor that [then US president] George Bush or [then UK prime minister] Tony Blair had allowed international inspectors, who should have confirmed the existence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, to finish their work.” (The third member of that trio, then Spanish prime minister José María Aznar, has not remained in the memory of even one of the world’s most informed people.) “Those observers had established that there was no evidence of weapons of mass destruction. Bush and Blair were anxious to defeat Saddam, who was certainly a ruthless dictator, but that fact alone did not justify the war. The degree of death and destruction that the war caused was much more than what Saddam could have inflicted on his population at that time.”

Finally, I ask him for his stance on the controversial debate about whether we should send arms to the Ukrainians. “Ukraine has been unjustly attacked by a brutal dictator who does not allow his own population to know the truth. Anyone who calls what is officially a ‘special military operation’ a war can be punished with 15-year prison sentences. Ukraine is a democracy that respects the rights of its citizens, and I think all countries that support democratic values and international law should support Ukraine, and that includes sending arms to the Ukrainians. The more difficult question, as the Russian army bombs Ukrainian cities, is whether to respond to president Zelenski’s petition to impose a no-fly zone, because that would implicate NATO countries in the conflict, and that comes with a lot of risk.”

Clearly, this mind has much more on it than cartoon monkeys and insolent journalists.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.