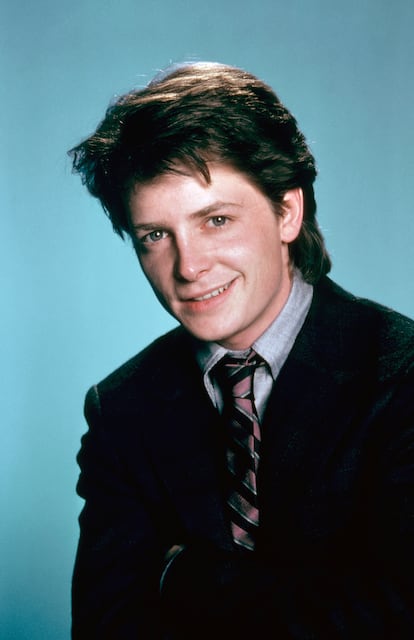

How Michael J. Fox learned to survive in Hollywood with a neurodegenerative disorder

In his memoir ‘No Time Like the Future,’ the actor recalls the last years of his career, how he kept working and incorporating the disease into his characters, and why he decided to retire in 2020

In 1991, Michael J. Fox received a piece of news that would change his life. At the peak of his career, months after the third installment of Back to the Future had made $244 million (€220 million) at the box office, a neurologist that Fox had gone to see after noticing muscle pain and shaking in one finger, gave him his diagnosis: Parkinson’s disease. In No Time Like the Future: An Optimist Considers Mortality, recently released in Spanish, Fox recalls the doctor telling him that he might be able to work 10 more years. He was 29 at the time.

The following months weren’t easy for him or his wife, actress Tracy Pollan. Terrified and trying to understand what the future would bring, Fox began drinking. The situation grew unsustainable. Encouraged by his wife, he sought psychological help to manage his demons. His son Sam, born in 1989, recalls that one of his earliest memories is going to the fridge to get a beer for his father. Therapy helped the actor stop drinking and strengthen his relationship with his family. In 1994, Tracy got pregnant with twins, Aquinnah and Schuyler, and in 2001 they welcomed another child, Esmé. “People felt strangely comfortable asking if we were concerned about bearing more children while dealing with the open-ended escalation of a major neurological disorder, and the fear that the babies could inherit the disease,” Fox writes. “The question could be construed as inappropriate, but the answer was: We weren’t concerned, nor should they be.” It remained to be seen how soon he would have to bid goodbye to the cameras.

Rather than make his illness public, Fox decided to continue working as long as his body would allow. The moment he feared arrived in the spring of 1998, during the filming of the series Spin City. “My character on Spin City didn’t have PD; so by the end of our second season, it was difficult for him to believably pass as physically uncompromised. Increasingly worried that my random movements would alienate the audience and alienate them if I did (Would they still think I’m funny if they knew I had PD?), I chose to publicly disclose my condition,” Fox remembers.

Fox made his condition public in November 1998. Two years later, after turning 40, he retired from show business because, according to him, his face had lost its past expressiveness. At that time he created the Michael J. Fox Foundation, an NGO that funds the search for a cure to Parkinson’s disease. In his memoir, Fox said he had always liked being an actor that editors would cut to at any time for an appropriate reaction, his face always alive in a scene. Whether speaking or not, he liked his characters to always be animated and engaged. But gradually, with the effects of Parkinson’s, “my face began retreating to a passive, almost frozen disposition.”

That hiatus didn’t end up lasting as long as Fox had expected. In 2004, after getting a call from Bill Lawrence, co-creator of Spin City, he agreed to appear in two episodes of the comedy Scrubs. The role of doctor Kevin Casey, an eccentric neurosurgeon with obsessive-compulsive disorder, allowed him to think about his professional future from a new perspective.

“I discovered that I could focus less on the externals and stop trying to hide my symptoms. This was in stark relief from my days on Spin City, when I’d keep a live audience waiting while I paced my dressing room, pounding my arm with my fist in a vain attempt to quell the tremors. On Scrubs, instead of trying to kill it, Invited my Parkinson’s with me to the set. I felt free to concentrate on the task that any actor, able-bodied or not, is charged with accomplishing: uncovering the internal life of another human being. Putting the emphasis on my character’s vulnerabilities and not my own, Parkinson’s could in fact disappear.”

Though he no longer held the star status of the 1980s and 90s, aside from his role as voice of the protagonist in Stuart Little, the small screen gave Fox an escape route. His minor characters on Boston Legal (2004-2008) and Curb Your Enthusiasm (2000), where he dared to turn his illness into humor, gave him a sense of salvation. His role on Rescue Me won him an Emmy in 2009 for Best Guest Actor.

Fox’s favorite role from that period was the lawyer Louis Canning on The Good Wife (2009-2016), who he played for 26 episodes over four seasons. “The Good Wife writers created a character who shamelessly exploits his own misfortune, converting it into an asset to win sympathy and jury votes. … Disabled and differently abled characters are always seen in a sympathetic light, soft piano music rising to crescendo as they achieve their relatively modest goals. This guy was different. He was debilitated, but no piano. He was an asshole.”

“Mine is not a mental disorder or an emotional one, although these issues can develop. It is neurological, and manifests in a corruption of movement,” Fox explains in No Time Like the Future. “Some people will focus on the slight palsy, the tremoring of fingers and limbs. That’s certainly a part of it. But at least in my experience these symptoms have become more manageable over time. Much more difficult to acknowledge and accept is the diminishment of movement.”

Fox’s case is special. His significant fortune allows him to face the illness and its consequences. But the Spanish Parkinson’s Federation notes that, beyond Hollywood, “it’s important for companies to promote positive measures and work accommodations to help people with Parkinson’s who want to remain active as long as possible. And in cases when they cannot keep their jobs, they should have social protections that adjust to their needs and allow for access to disability support.”

Fox’s health declined considerably at the end of 2017. Alarmed by a sudden tendency to collapse onto the ground, in January 2018 he had an MRI. An old spinal cord tumor, which had been under control for years, had started to grow.

“Given the size and location of the tumor at the cervicothoracic junction, it is risky. I mean, who wants to be the guy who paralyzes Michael J. Fox?” The words from doctor Nicholas Theodore, director of the Neurological and Spine Center at Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, didn’t bother him in the least. On the contrary: “I tend to trust folks who make me laugh when things get grim.”

Despite the fact that in April 2018 the tumor was successfully removed, Fox spent the following months in intense rehabilitation sessions to recover his mobility and control of his movements.

On August 13 of that same year, a fall set back Fox’s recovery. Spike Lee had offered him a brief cameo in See You Yesterday, a movie about time travel–with a wink to Back to the Future. That morning, Fox had been elated to return to a film set, but he had to cancel his appearance after he fell to the floor of his New York apartment. “My family has put up with so much crap. Four months since I had major back surgery, and I gambled the health and the security of my family by being a fool,” he wrote about the unexpected accident that shattered his humerus.

After another round in the operating room, which left him with 19 screws in his arm, Fox’s characteristic optimism vanished. He fell into an existential crisis tinged with depression. “Counterintuitively, Parkinson’s and the tumor on my spine were easier to accept than my fracture. The arm crisis was there in an instant, an explosion. A cataclysm. I am unprepared for the fallout. My mood darkens,” he recounts in the book.

The third act

In 2019, Fox’s luck changed. Spike Lee offered him the possibility of filming that leftover scene from See You Yesterday. And in the fourth season of The Good Fight, the sequel to The Good Wife, he once again took on the role of Louis Canning. The sensation of returning to familiar territory was a relief. But he soon realized that production had a smaller budget and a tighter schedule. At the same time, he started to have trouble pronouncing certain words in the script.

“Now, my work as an actor does not define me. The nascent diminishment in my ability to download words and repeat them verbatim is just the latest ripple in the pond. There are reasons for my lapses in memorization–be they age, cognitive issues with the disease, distraction from the constant sensations of Parkinson’s, or lack of sensation because of the spine–but I read it as a simple message. Everything has its moment, and my time of working 12-hour days and memorizing seven pages of lines has ended. At least for now.”

Many other public figures, including the actress Helen Mirren, the boxer Muhammad Ali, the musician Ozzy Osbourne and the painter Salvador Dalí have faced struggles with Parkinson’s. Michael J. Fox announced his definitive retirement in November 2020, at age 59, a full 20 years later than his neurologist had predicted in 1991. And that may be the biggest success of his career.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.