Medellín demolishes Pablo Escobar’s museum house, putting an end to the notorious legend

The building was once the main attraction of narco tourism in the Colombian city

At the entrance, visitors are welcomed by Roberto Escobar, a nearly blind man with square-rimmed glasses, a red cap and a neatly tucked-in shirt. “Welcome, this is your home,” says Pablo Escobar’s older brother. After his ex-wife (a 1990s beauty queen) takes your $50 admission fee, Roberto guides you through the house. There’s a portrait of Pablo Escobar with Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone, the Russian fur hat he wore during a visit to Moscow, Bonnie and Clyde’s car, a desk with secret places to hide weapons, an armored SUV with openings for shooting from the inside, a painting of Terremoto (a Paso Fino horse castrated by Escobar’s enemies), a jet ski and giant $500 bill. The mansion that inadvertently paid tribute to kitsch and retro aesthetics later became a shrine to the most notorious criminal in Colombian history.

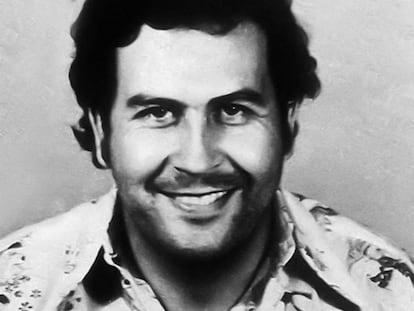

Pablo Escobar’s Museum House is now a thing of the past. On July 10, 50 Medellín officials arrived with diggers to bring down the building, only to discover that Roberto had already beat them to it. All that remained on the empty lot was an enormous safe. A judge had ordered the demolition of the building because it lacked the necessary municipal permit. But behind the bureaucratic maneuver was a desire to put an end to narco tours of the city that showed off Escobar’s many houses, murder sites and even his grave.

Escobar’s museum was located in Loma del Indio, in Medellín’s Poblado neighborhood. The gate at the entrance is adorned with a photo of the airplane Escobar used for his inaugural cocaine shipment. A walkway leads to Roberto’s home, which is adjacent to the demolished museum building. Back in its heyday, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) tagged Roberto as the number two man in the Medellín Cartel, the drug cartel led by Pablo that flooded the United States with cocaine. The cartel openly warred with the Colombian government when it tried to extradite captured members to the U.S. Roberto, the cartel’s chief accountant, once decided that the best way to count the enormous amounts of cash coming in from drug sales was to weigh it on scales.

Unlike his brother Pablo, who was a fugitive until he was killed on a Medellín rooftop by Colombian special forces in 1993, Roberto turned himself in to the authorities twice — he saw no heroism in dying. The museum walls were covered with photos of cartel characters — Pinina, Tayson and Pablo himself — men who murdered hundreds of people before dying violently themselves. Roberto made it to old age — he’s now 75 — but he didn’t emerge unscathed. During one of his prison stays, he was partially blinded by a letter bomb that exploded in his face. Roberto’s blue eyes are now covered with a transparent, gray film, and he occasionally takes out a small bottle of artificial tears to moisten them.

Before becoming his brother’s partner in crime, Roberto was an outstanding cyclist who was nicknamed “El Osito” (Teddy Bear) because he once crossed the finish line of a race completely covered in mud. Not recognizing him, the radio announcer said, “Here comes a teddy bear.” Roberto competed for several years in Colombian bicycle races and won a gold medal in Panama. Little Pablo and his schoolmates started affectionately referring to his famous older brother as “Osito.” Years later, the tables were turned and history will remember Roberto as the brother of one of the most infamous gangsters to have ever walked the earth.

Pablo Escobar has frequently been glorified in books, tabloids, television and movies. Alfonso Buitrago, a journalist from Medellín, has recently authored a book about a former schoolmate of Escobar who eventually became his personal photographer. Buitrago vehemently opposes trivializing acts of evil and says it can have far-reaching consequences.

“Tearing down El Osito’s museum is the city officials’ way of fighting against the romanticization and commercialization of the Escobar legend,” said Buitrago. “The place raised so many doubts, particularly because El Osito’s narrative twisted the history of the Medellín Cartel and narco-terrorism for tourists. It’s hard to believe that Medellín still doesn’t have a place to share its complex story about our narco past. Ever since [former mayor] Federico Gutiérrez was in office, they’ve opted to destroy this history instead of creating collaborative public processes to help Medellín truly grasp its present, past, and future.”

Roberto is an affable man who was very attentive to museum visitors, but he glossed over the horrifying story of his brother, Pablo. A bombing in Bogotá that claimed 25 lives? Blame the authorities. An airplane explosion in mid-flight with over 100 people on board? Blame the enemies who tried to pin the blame on Pablo. In Roberto’s eyes, Pablo was a modern-day Robin Hood. The demolition of the museum has removed one more brick in the Escobar myth, enabling Medellín to begin eradicating this unsettling legacy.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition