How a cigarette pack became a form of anti-Franco resistance

A new exhibition showcases apparently insignificant objects that were nursed as treasures by the families of the executed and the exiled

Exhibit A: a cigarette pack kept for 80 years because it bears a farewell message on the back from Vicente Verdejo to his wife and family, written in the knowledge that he has smoked his last cigarette and given his last hug.

“Carmen, I am using this pencil to say goodbye to you and our children, my Gregorio and my Vicentita,” he says. “I will die thinking about you. You have been so good and don’t deserve what is happening to you. Resign yourself and be patient. Accept all the affection from this man who will love you until he dies.”

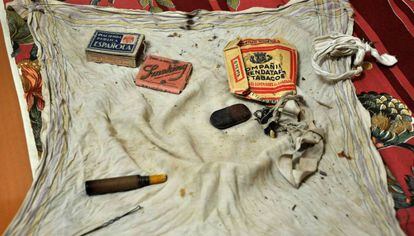

Exhibit B: a handkerchief stained with blood kept for decades because it holds the belongings that Heliodoro Meneses carried on him the day he was executed: cigarette papers, a box of matches, a pencil stump, a rubber and a hairpin.

A new exhibition called Las Pequeñas Cosas (or, The Small Things) is the result of research carried out by experts from the National Distance Education University (UNED) who spent 10 years unearthing objects kept by individuals in memory of loved ones persecuted by the Franco regime. Inaugurated this month in Madrid, it is a traveling exhibit that will be on display throughout in all the locations where the distance learning institution has a physical base.

For years, these objects represented a form of resistance. Keeping them meant rebelling silently against those who tried to make their owners disappear, either by dumping them in mass graves or sending them into exile. Over time, they also served as a badge of pride and a springboard to help others understand the effect of the loved one’s absence.

Vicente Verdejo, the man who penciled his goodbye to his family on the back of his cigarette box was executed on October 29, 1940. Gregorio, his son, was six and his daughter Vicentita, two. “My brother started working before he had his [permanent] teeth. He couldn’t have been more than eight or nine,” says Vicentita. “We were so hungry...”

When Heliodoro Meneses was executed, one of his cousins was present. When the bodies were left on the ground, waiting to be thrown into a mass grave, he approached his dead relative and emptied his pockets of his personal belongings. The family kept these in a scarf, a humble collection of treasure, which is now among the “small things” on display.

“It’s an exhibition filled with wrinkles, stitches, scraps… small things that let us see and understand this country’s past,” says the anthropologist Jorge Moreno, one of the exhibition’s curators. “There are photos, bits of writing and objects that keep within their folds the exact form of a memory that has had to be stitched together, cut out and whispered in order to survive.”

Banned names

While the exhibition displays items linked to both executed and exiled prisoners, it also features curiosities from the archives of various institutions; in the case file of Rufina Delgado’s summary trial, for example, researchers stumbled across a handwritten subversive version of Cara al Sol, the anthem of the Spanish fascist Falange. And in the Civil Registry, they found the name “Libertad” (Freedom) crossed out and replaced by the name “Máxima” in accordance with a 1939 law that obliged parents to change “exotic or extravagant” names within 60 days. Those children whose parents failed to comply would find themselves with the name of the Catholic saint whose day it was, or a saint worshiped in the vicinity.

The exhibition also displays items belonging to exiles that would seem to have little significance, but which comforted those who were banished from their homeland, such as the small pieces of coal taken to France by Alejandro Trapero, a miner from Puertollano, who kept them on display in his living room.

The exhibition also features a letter in which a prisoner named Anastasio Godoy asks his family to sell a wardrobe in order to buy stamps and paper on which to write to him. The subsequent correspondence was, and still is, priceless.

Las Pequeñas Cosas is on display at the Escuelas Pías de UNED-Madrid center until January 8. For subsequent locations, consult mapasdememoria.com

English version by Heather Galloway.