The 2,300-year-old winery concealed in a Spanish mountain

The archeologist who discovered the Phoenician site in Cádiz wants to create an information center on the history and culture of wine

It may look dry and sterile on the surface, but few mountain ranges can boast about holding as many secrets as the Sierra de San Cristóbal, in Spain’s southern Cádiz province.

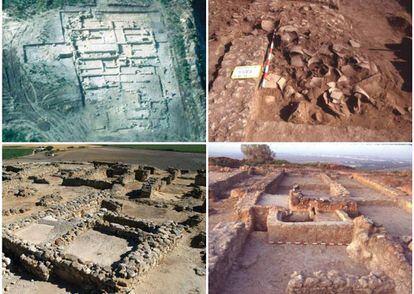

Some parts of the mountain were dug out into enormous, phantasmagorical underground quarries, while others were used to supply water to the nearby location of El Puerto de Santa María. And on what looks like an ordinary hill covered in scrub, archeologists found the oldest known complete winery in Western civilization.

This is not just the history of my town, this is world history

Diego Ruiz Mata, archeologist

The facilities were used to produce wine in the 3rd century BC, and artifacts found at the site suggest that it also hosted religious rituals in which wine was used to establish contact with the gods.

And yet this invaluable legacy continues to languish ever since its discovery in 1991. “Even though there is some earlier archeological evidence of winemaking in the Levante area, San Cristóbal is a complete winemaking facility covering 2,000 square meters. It is unique,” explains Diego Ruiz Mata, an archeologist and professor of prehistory.

It was Ruiz Mata who led the dig that uncovered the site. A few years later, he warned about the risk of damage to the historical remains. “That place became a motocross circuit. They were using the walls to jump over them, so they had to be covered.”

Ruiz Mata now wants the site to serve as an information center on historical wine-production techniques in an area known today as Marco de Jerez, which continues the winemaking tradition as a modern producer of sherry.

If his proposal bears fruit, the site would become a new destination in a network of archeological sites that are open to the public in the area. The foothills of San Cristóbal are also home to the Doña Blanca site, where a Phoenician city from the 8th century BC once stood. Although wine consumption was first recorded in the East during the Neolithic era, it was the Phoenicians who extended its use in Europe.

The winery dates back to the 3rd century BC. It was also at this time that the port facilities were expanded, making it the largest one in the region. Both sites bear witness to how important this city must have once been. The winery was part of “a major industrial zone covering at least seven hectares,” notes Ruiz Mata. Other activities included salting and the production of purple dye.

Wine was appreciated because it could place you in a psychotropic state that brought you close to the gods

Diego Ruiz Mata

During the excavation work, the archeologist found two wine presses, ovens to heat and produce sweet wine, and storage spaces with amphorae to preserve the liquid. Nearby, there were three temples that recorded the different uses that wine was put to at the time.

“Besides the social use that we know today, wine was appreciated because it could place you in a psychotropic state that brought you close to the gods,” says the archeologist. One of the temples contained a pit for offerings, and it was filled with amphorae that were hurled in during ritual banquets. Another temple yielded sacred stones, and a third turned up a basin used to sprinkle liquids on the gods.

The wine also had value because it was a scarce good. “It was considered the drink of the gods,” says Ruiz Mata.

Once they had crushed the grapes, the residents of Doña Blanca would mix the wine with fruit and heat it inside the ovens at 200ºC. This produced a sweet, fruity wine halfway between sangria and a syrup. This is what the Romans later called defrutum, or cooked wine.

The wines that now come out of the Marco de Jerez region – the sherries, finos and olorosos – have little to do with those wines of the past, but Ruiz Mata thinks that the wineries of today should be the ones to lead the drive to recover the wineries of the past.

“Their recovery would be possible if they are dug and restored with assistance from Marco de Jerez entrepreneurs,” he says, suggesting a public-private partnership. An information center around the history and culture of wine, he adds, “would be a highly valuable attraction. This is not just the history of my town, this is world history.”

English version by Susana Urra.