Building the case against Assad’s regime

20, 21, 24, 28, 34, 36, 40, 41, 83, 90, 92, 124 and 126. Yazan Awad repeats the days he was tortured like a mantra; the days the military prison guards smashed his legs with a club for six hours solid; the days they suspended him from the ceiling and beat him; the days they pushed a Kalashnikov up his rear. And the worst day of all; day 36.

Awad joins other victims, witnesses and lawyers in Germany where the legal battle against Bashar al-Assad’s government is being waged. Almost 1.5 million refugees have flooded into the country over the last two years, and many are living proof of the atrocities committed in the regime’s prisons. Their presence, along with thousands of photos and Germany’s universal justice laws, has not only meant that cases such as Awad’s are being heard, but that the first international warrant has been issued for the arrest of a high-ranking official in the al-Assad regime.

In a room a thousand kilometers from Berlin, the evidence needed to nail the culprits is stored in hundreds of cardboard boxes. This ‘who’s who’ of torture consists of hundreds of thousands of documents that have been smuggled out of Syria over a period of years showing who designed the gruesome game plan, who issued the orders, who carried them out and who turned a blind eye.

These documents have been classified by veterans of the international justice system and are now driving investigations in a dozen different countries against middle-ranking Syrian government officials who have moved to Europe. But, more importantly, they are being used to construct a case against the al-Assad regime in order to avoid a Yugoslavia or Rwanda scenario, where a lack of evidence meant delaying justice for decades and, in many instances, forever. These documents mean that when the time comes for justice to be done, the evidence will be ready and waiting – the loopholes plugged.

[Exhibit A. Refugee accounts]

Los de Awad son recuerdos muy nítidos

No quiere olvidar

Habla rápido

Al escuchar su relato, resulta difícil creer que sigue vivo

The first body of evidence against the Syrian regime is contained in the victim’s statements, which depict its repressive apparatus in grisly detail and reveal a pattern of systematic abuse. Over and over, their stories recount the pipes on the ceiling and the cables used to hang prisoners for beatings; the relentless cries of those being tortured; the overcrowded cells rife with infection; the uncertainty of not knowing if they would be alive the next day; the disappearance of fellow prisoners; the confessions wrung from them. And now, a desperate faith in justice that is keeping their spirits from breaking.

Awad is a big guy; a 30-year-old who sought refuge in Germany two years ago after being imprisoned in the al-Mezzeh airport – which was under control of the Syrian military air force – for 137 days. “As soon as I arrived, they beat me for six hours. They lay us on the ground and beat us with pipes. They beat the soles of our feet. Then they put me in a cell with 180 people. The pain was terrible. I couldn’t go to the toilet. Two people had to drag me there.”

Awad’s story pours out of him. “They beat me like crazy – my head with their boots and with the butts of their Kalashnikovs,” he says. “They stuck an AK-47 up my ass and I ate nothing for two months. It was dangerous to ask to see the doctor; for every 10 that went, only one would come back alive. They gave us 10 seconds to go to the toilet. In that time you had to drink, tend to your injuries, go to the bathroom and clean up.”

Awad describes what happened on day 36:

“They told me they were going to kill me,” he says. “I was still hanging from the ceiling and they put a gun in my mouth and they told me to recite the shahada [the Islamic profession of faith]. I couldn’t stop stuttering and it took me more than 15 minutes. Someone fired a shot. They had cut the rope and I was on the ground. I thought they had killed me. They took the bandage from my eyes and I ran after them. I needed to see their faces so I could explain to God who they were on Judgment Day.”

Awad had been a regular guy, living an ordinary life. Then, on April 29, 2011, he joined his first demonstration against the regime. The Arab Spring had seen the fall of Tunisian dictator Ben Ali and Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak and suddenly anything seemed possible, even in Syria. The photos portraying the torture of the Daraa children acted as the catalyst. These were 14-year-old schoolboys whose only crime was to deface a public wall with the slogan, “Your turn doctor,” referring to Bashar al-Assad’s training as an ophthalmologist.

“When I saw the photos of those children, I decided to fight the regime,” says Awad. First there were the demonstrators, like Awad, then came those who would help the demonstrators escape arrest and, finally, there would be a network of underground doctors and hospitals to tend to the injured involved in the protests.

The start of the conflict in Syria was infused with hope, a sentiment that has been stamped out along with the lives of around 400,000 people. Now, in its eighth year, the conflict has also forced 11 million from their homes, amounting to almost half of the population. But perhaps worst of all, there is still no political solution on the horizon and no end to the suffering in sight.

Despite all this, Awad is filled with a sense of purpose. “My friends are still in jail and I promised I would get them out. My dream is to speak in front of the UN Security Council. In 2012, they stopped the torture for two weeks and we were able to sleep because the cries and screams also stopped. And they gave us food. It was only in case UN inspectors came to check out the prison. Those two weeks were incredible. Paradise in hell.”

After seeking asylum, Awad encountered the renowned Syrian lawyer Anwar al-Bunni – who had also moved to Germany – through the internet. His strategy began to take shape. “My time had come,” he says.

Al-Bunni is a human-rights activist whose easy smile belies a harsh reality of years in prison. He and his colleague Mazen Darwish are central to building the case against the Syrian regime, and are supported in their efforts by the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), a German NGO for strategic litigation.

Together they plan to put the regime’s torturers behind bars. Up to now, they have presented four criminal charges to the Attorney General, along with thousands of photos of torture victims. While countries such as Sweden, Norway and Austria also allow for the application of universal justice, in Germany the law is flexible enough to carry out “structural processes” in which evidence can be compiled without having to relate to specific cases.

There is also a department for public prosecution and a criminal police department that take an interest in such cases. Two years ago, for example, the department for public prosecution issued an international warrant for the arrest of a member of Islamic State for war crimes committed against the Yezidi Kurds.

Now, after listening to witness accounts, the same department has just issued an international warrant for the arrest of Jamil Hassan, director of the notorious Air Force Intelligence Directorate and a close associate of Bashar al-Assad.

In Damascus, al-Bunni was the go-to defense for political prisoners and when he got to Europe, the refugee community quickly sought him out. Soon he was inundated with messages from fellow Syrians who, like Awad, wanted his help and were keen to talk.

In next to no time, he was able to compile first-hand accounts from all over Europe. From his office in the north of Berlin, where the only decoration is the Syrian flag, al-Bunni explains: “We are preparing witnesses in Norway and also in Stockholm. There’s a case going on in France brought by two victims with French nationality…” In total, there are five Syrian lawyers working in Berlin and another 30 scattered across the rest of Europe. He explains that among the 27 they are seeking to indict is Bashar al-Assad himself.

Activism runs in al-Bunni’s blood. Between himself, his four brothers and his sister, they have chalked up 75 years in jail. Back in Damascus, al-Bunni was director of a well-known human-rights center that acted as a point of reference for western diplomats and European institutions. Accused of seeking to debilitate the country and of collaborating with international organizations, he spent five years in prison between 2006 and 2011. During that time, he says they tried to kill him twice.

Al-Bunni was actually behind bars when the revolution took off in Syria. Following his release, Germany offered him asylum – his work had previously been recognized by the German Association of Judges. But al-Bunni stayed. Demonstrators were being arrested without any guarantee of charges or trials and al-Bunni made it his business to find them and secure their release. In 2012, his partner and friend Khalil Maatouk disappeared. Al-Bunni kept going until 2014 when the government ordered his arrest. Aware that his life was on the line, he fled to safety with his wife and children.

I promise I will put them in jail, dead or alive; these people cannot be part of the political transition

Anwar al-Bunni

“We know there are more than 60 people from the regime in Europe, but I am not scared of them,” says al-Bunni. “They should be afraid of me. They know me from my time in prison. They interrogated me every day and they know that the only way to shut me up is to kill me. If they kill me in Germany, it will be easy to catch them and they will go to jail and I will have achieved my goal.” He laughs. “I promise I will put them in jail, dead or alive; these people cannot be part of the political transition.”

Al-Bunni is convinced there is a lot at stake for Europe too. “If we let the al-Assad regime go unpunished, it will be like giving carte blanche to the world’s dictators. If international law collapses, what will become of our societies?” he says.

Al-Bunni is also part of a project that makes use of his contacts among the refugee community to track down criminals coming to Europe in the guise of refugees. These could be either officials from the regime or members of Islamic State and al-Nusra – Syria’s al-Qaeda affiliate. “We know that more than 1,060 people with refugee status here have committed crimes,” he says. “And there’s a lot of evidence to prove it.”

The German police department for war crimes (ZBKV) is also collaborating, and a spokesman explains that systematic checks are done on anyone coming in from Syria or Iraq since 2015, when the number of asylum seekers spiked. The checks have revealed more than 4,300 pieces of information related to possible violations of international law, including genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. “We send specific cases of potential suspects to the Attorney General in Germany,” he says.

[Exhibit B. Photos of the horror]

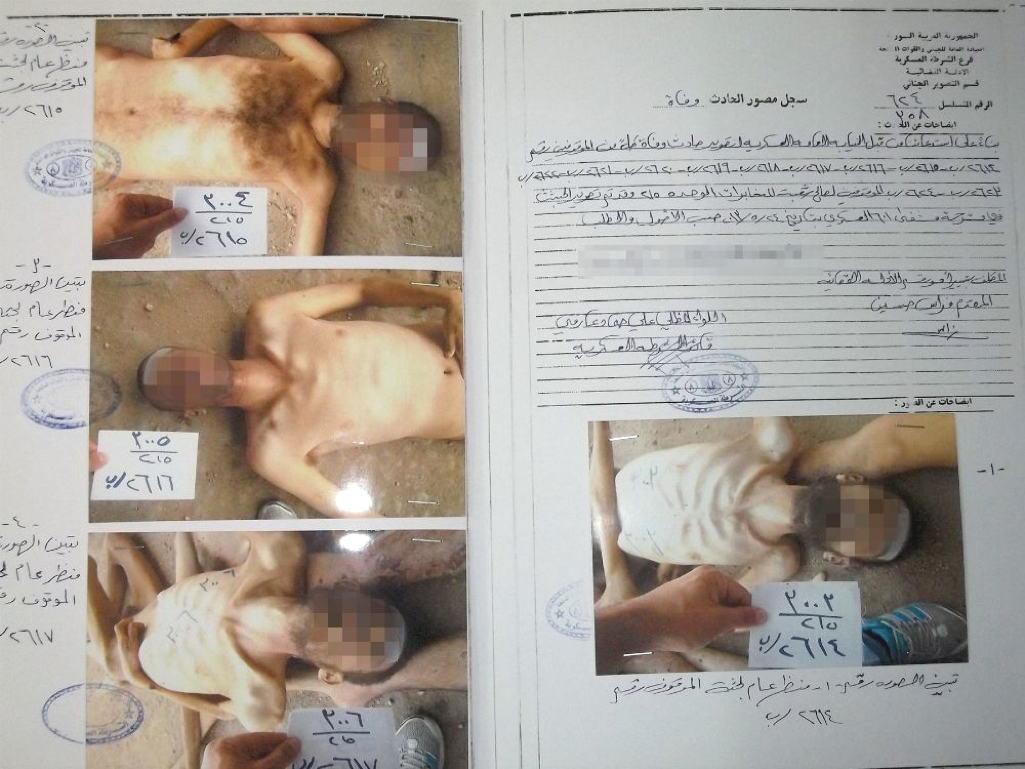

Among the documentation with the Attorney General is a crucial package containing 26,948 photos. Almost half of them show the dead bodies of detainees. They are known as the Caesar photographs, after the military defector who smuggled them out of Syria.

Caesar was a forensic photographer with the military police. Between 2011 and 2013, his job was to photograph the corpses from the different prisons arriving at the 601 Military Hospital in Mezzah and the Tishreen Military Hospital, both in Damascus.

The photos are professional and show clear evidence of starvation, infection and torture. We have presented less-graphic versions here due to their disturbing content.

Many families have been able to identify their loved ones in the images after years of fruitless searching. These photos provide proof. In March 2017, the Spanish High Court embarked on its first case against the al-Assad regime when Syrian-born Spanish citizen Amal Hag-Hamdo Anfalis recognized her brother’s body in Caesar’s photographs.

However, the court backtracked several months later on the basis that Spain has no jurisdiction to investigate such crimes.

Besides providing proof of identity, the images offer evidence of systematic abuse and the subhuman conditions within Syria’s detention facilities. Most of the bodies are emaciated, their bones jutting and their skin showing infection and sores as well as evidence of torture. There are marks indicating strangulation, burns and beatings; mouths whose teeth have been smashed and eyes filled with blood.

Amnesty International estimates that 17,723 people have died in these detention centers, and catalogs a wide range of torture they believe to be the norm rather than the exception. “Since peaceful demonstrations began in 2011, the Syrian government has embarked upon a campaign of arrests and forced disappearances. Thousands of people have been tortured and abused, many dying in detention and thousands going missing.

The government has targeted activists, human rights champions, journalists, doctors and humanitarian workers, according to Amnesty International’s most recent report.

The photos from the Caesar files contain more information than you might think at first sight. Next to each body is a piece of paper containing three figures: the number of the detention center where the victim was held, their detainee number and the number issued by the forensic doctor.

123

1231229

215

4745

Detainee number, assigned by the security branch

Security branch number, in this case the infamous “Branch of Death”

Death number, assigned by a forensic doctor after death

3003

215

2614

3004

215

2015

3005

215

2616

3006

215

2017

These books (above) are the records of the dead. The forensic doctors’ reports that also came from Caesar indicate where the victims were imprisoned – for example, 215 is nicknamed “the prison of death” – and which morgue the bodies were sent to.

So many corpses ended up in Hospital 601 that there was no more room in the morgue’s cold chambers. Consequently, the bodies were stored in the hospital’s garage, which was normally used to repair military vehicles.

If the camera’s GPS was activated, the metadata allows for the verification of where the photos were taken and which institutions were responsible for the abuse. In 2015, Human Rights Watch published a dossier entitled If the Dead Could Speak in which forensics analyzed the images (some of which include dates and coordinates). And technology allows us to make the sinister journey to the place where the abuses took place, using Google Earth.

In collaboration with ECCHR, the Caesar Files Group used the photos as evidence to file criminal charges against the heads of Syria’s intelligence services and military police at the Attorney General’s Office in Karlsruhe, southwest Germany, in September 2017.

The Attorney General’s Office is unable to divulge the progress of its investigations, but an email confirms that “in relation to the civil war and the war crimes in Syria, particularly those committed by the Syrian regime, we are concluding a structural process. We are analyzing the so-called Caesar files, which expose the cruelty of the al-Assad regime. They show numerous bodies bearing signs of different types of torture […] We have photos from 2016 that are being analyzed by a forensic institute. Within this context, we are trying to identify bodies and establish the cause of death. The

investigations are ongoing.”

Concerning the arrest warrant for Jamil Hassan, revealed by Der Spiegel and confirmed by lawyers, the Attorney General’s office refuses to confirm it officially, though they do not deny it.

Ibrahim Alkasem, a Syrian lawyer collaborating with the Caesar Files Group, agreed to meet with EL PAÍS on the condition that neither his current address nor the location of the interview were revealed.

“We have been gathering papers – victims’ accounts, prison-transfer documents – and videos since 2011,” he says. “The photos show clear evidence of systematic torture with the perpetrators following a specific pattern of instruction. It is very methodical and widespread. The archives from the Caesar report form part of the evidence, but only a part,” adds Alkasem, who is also compiling official documents showing how the chain of command operates and who is in the know about the atrocities.

While the legal battle against the al-Assad regime is being waged in Germany, there are also less high-profile cases underway in Spain, France, Austria and Sweden. And besides symbolic trials that are played out in absentia, there are short-, medium- and long-term strategies at work.

“The German justice system has understood the importance of gathering evidence that can be used later in specific cases. It is a job the NGOs can’t do alone and that is a very important step forward,” says Julia Geneuss, an expert on universal justice from Hamburg University. “At the start Germany was very cautious when it came to universal justice cases, but it has realized that it is not so much about holding a particular trial here as the fact the evidence can be used further down the line in

international tribunals.”

Geneuss explains that Germany has the broadest interpretation in Europe of universal justice. Here you can begin a judicial process without the victims being citizens, unlike in the rest of Europe.

[Exhibit C. The documents from the chain of command]

In another corner of Europe whose location is being kept under wraps, the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) carefully files the documented evidence of abuse. One-hundred-and-forty-five legal experts from around Europe and the Middle East have already compiled 800,000 pages of incriminating evidence.

Similar circumstances in Yugoslavia, Cambodia and Rwanda have taught CIJA that to build a case against a regime, it is essential to have evidence of who is who in the hierarchy of terror, their position, when it was held, and the extent of their knowledge and accountability.

These boxes of evidence have emerged from Syria in recent years thanks to a complex logistical operation:

A limited number of people have access to this catalogue of terror, which is guarded by security cameras. All visitors are required to sign in and out. Once over the threshold, they are faced with 265 boxes, all identical and containing bar-coded files that in turn contain the key to justice in Syria.

Bearing the initials of Syria’s National Security department, one lists categories of people to be detained, including demonstrators and people in contact with foreign journalists. “Clean all sectors of these people,” one document reads. Another asks that any new names extracted from interrogations be sent to the National Security office. There are also notes taken during interrogations.

Nerma Jelacic, deputy director of CIJA, who gained ample experience at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, explains that it is not enough to have a document with a signature, you have to have all the papers pertaining to that document in order to demonstrate its authenticity. Otherwise, the evidence is easily dismissed in court.

Jelacic explains that in the case of the Bosnian conflict, the tribunal was set up 1993, two years before the Srebrenica genocide, but it wasn’t until seven years later that those responsible were brought to trial. According to Jelacic, one of the problems was the lack of evidence to prove that people such as Ratko Mladic knew what was going on.

The trick is to collect proof while the conflict is still in progress. Waiting until the war is over is invariably too late. Acting quickly and seizing opportunities when they arise is fundamental, according to Chris Engels, director of CIJA Operations and Investigations.

“Some of the places we rescued these documents from have been recaptured by the regime and it would be impossible to get them back now,” says Engels, who explains that this is the first time so many documents have been compiled during a conflict.

“The evidence of torture is extensive. There are thousands of very similar stories from across Syria; the same questions asked and the same methods of torture used.” But in the CIJA, it is not just the atrocities committed by the regime that are under scrutiny, it is also the crimes committed by opposition groups.

“What we are doing is absolutely revolutionary,” says Jelacic. “We have already completed 60 cases against high-ranking officials. Now all we are lacking is the trial. We need the political will and right now it’s not there. But it will be and when it is, we will have all the evidence ready.”

The papers will be used in a macro-international trial just as soon as China and Russia stop boycotting the investigation into war crimes committed in Syria. But it will also be used to bolster current cases. An increasing number of the perpetrators are settling in Europe, masquerading as refugees. CIJA is offering evidence to the dozen countries trying to take them to court.

At the end of 2016, the UN General Assembly set up a framework for the Independent Investigation in Syria, also designed to analyze evidence of crimes and human rights abuses and to prepare judicial dossiers to support cases that are underway in national courts of justice.

Wolfgang Kaleck is the founder of ECCHR, which has just issued an international arrest warrant against Hassan. He believes universal jurisdiction is sweeping not only across Germany, but also across the north of Europe. And although he is aware of the complexity of the task ahead, he believes it is important that international arrest warrants are issued. “If a German High Court is investigating crimes in Syria and attributes responsibility to senior officials in the al-Assad regime, that carries a lot of weight,” he says.

“The culprits aren’t going to be able to be tried in absentia, but the international arrest warrants send the message to the perpetrators that the crimes will not go unpunished,” explains María Elena Vignoli, an expert in international justice from Human Rights Watch.

As such, for many Syrian refugees, the German justice system is currently its only hope. Maryam Alhallak is one of them: in 2012 they took away her son.

In 2012 her son was arrested at the University of Damascus

His crime? Belonging to the student union

They took him to the security branch 215

The “Branch of Death”

A fellow student told his mother what happened

Last July, Maryam Alhallak testified in court, explaining how she managed to confirm that her son was dead after seeing him among Caesar’s photos. Prior to this, she had spent three years in Damascus searching for his body in vain. “The government was looking for me and wanted to arrest me,” she says. “I went to call on all the officials, which is why they were after me and threw me out of my home.”

A “mother courage” figure who nobody wanted to listen to. However, the German justice system has been keen to hear her story and that of her son, who was a supervisor in the Odontology faculty. “There were no charges against him,” she says. Her voice breaks.

She takes a deep breath and, referring to the trial, continues: “I am very hopeful. Justice is all that is left to us.”

English version by Heather Galloway.