Education: The world’s biggest scam?

The problem is no longer the lack of schooling but rather that once children get there, they do not learn

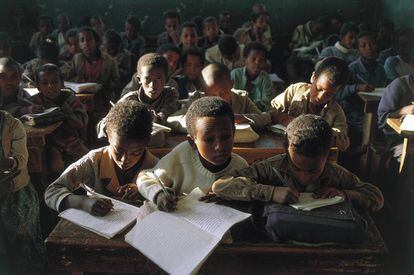

Every day 1.5 billion children and adolescents around the world go to buildings called schools. Once there they spend long hours in classrooms where some adults try to teach them how to read and write, math, science and more. Annually, this costs 5% of the world’s GDP.

A large part of this money is wasted. An even greater waste is the time lost by those 1.5 billion students who learn little or nothing that will be useful to succeed today’s world. The effort that humanity makes to educate children and young people is as titanic as its results are pathetic.

The effort that humanity makes to educate children and young people is as titanic as its results are pathetic

In Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, 75% of third grade students do not know how to read a phrase as simple as “the name of the dog is Puppy.” In rural India, 50% of fifth-graders cannot subtract two-digit numbers, such as 46-17. Brazil has managed to improve the skills of fifteen-year-old students, but at the current rate of progress it will still take them 75 years to reach the average mathematics score of students from rich countries; in reading, it will take more than 260 years. These and many other equally disheartening facts are in the new World Development Report, published annually by the World Bank. The central message of the report is that schooling is not the same as learning. In other words, going to school or high school, and getting a diploma, does not mean that the student has learned much.

The good news is that the progress in schooling has been enormous. Between 1950 and 2010, the number of years of schooling completed by an average adult in lower income countries tripled. In 2008, these countries were incorporating their children into primary education at the same rate as higher-income nations. Clearly, the problem is no longer the lack of schooling but rather that once they get there, they do not learn. More than an education crisis, there is a learning crisis. The World Bank report emphasizes that schooling without learning is not only a missed opportunity, but also a great injustice. The poorest people suffer most from the consequences of the low efficiency of the education system. In Uruguay, for example, sixth grade children with lower income levels fail in mathematics five times more than those from wealthier households.

The same happens with rich and poor nations. The average student in one of the poorest nations performs worse in mathematics and language than 95% of students in rich countries. All of this evolves into a kind of diabolical machinery that perpetuates and increases inequality, which, in turn, creates a fertile breeding ground for toxic politics and all kinds of conflicts.

The World Bank report emphasizes that schooling without learning is not only a missed opportunity, but also a great injustice

The reasons for this “educational bankruptcy” are multiple, complex, and not yet fully understood. They range from the fact that many of the teachers are as ignorant as their students and their absenteeism is inexcusably high, to the fact that their students are malnourished or too hungry to pay attention or that they simply do not have books and notebooks. In many countries, such as Mexico or Egypt, for example, the teachers unions are formidable obstacles to change, and corruption in the sector is often high. What’s more, important, sizable portions of the national budgets for education never reach the intended beneficiaries, the students, but rather the bureaucrats who control the system. National leaders usually let this negative trend continue for years, building entrenched and difficult-to-change organizations within governments and unions.

What to do? Start with measuring. For political reasons, many countries are reluctant to be transparent about the result (often dismal) of their students and teachers’ evaluations.

And if a nation’s leaders, and the public, do not know which educational strategies are working and which are failing progress remains elusive.

If a nation’s leaders do not know which educational strategies are working and which are failing progress remains elusive

A second goal should be to start giving more weight to the quality of education. While it is politically attractive to announce that a high percentage of young people in a country go to school, that is of no use if the vast majority of them learn little. Third: start earlier and include school breakfast and lunch. The better the education system is at the early ages, the more capable the children will be as they move through primary and secondary school. Fourth: use technology selectively and not as a magic bullet. It is not. Finally, raise the social and professional status of teachers through pay, training with modern pedagogical techniques and professional credentials.

Perhaps the most important message is that lower-income countries are not condemned to have children who don’t learn. In 1950 South Korea was a country devastated by war and had very high illiteracy rate. But in just twenty-five years it has managed to create an education system that produces some of the best students in the world. Between 1955 and 1975 Vietnam also suffered a terrible conflict. Today, their fifteen-year-old students have the same academic performance as those in Germany. It can be done. Where there a will, there is a way.

Follow me on Twitter @moisesnaim