In the Mexican state of Veracruz, death has no face

EL PAÍS reconstructs the last hours of Génesis Urrutia, a student who was found dead in early October

In a premonitory message to her ill mother, Génesis Urrutia recorded the following statement: “Death has no age.”

Four days after burying her daughter, Ramona Ramírez Ureña recollects that message as she sits on the porch of her home in Jáltipan, a town of around 33,000 souls located a four-hour drive from the port city of Veracruz.

These days, downtown Veracruz is falling apart and the violence keeps tourists away

In this modest municipality in southeastern Mexico, as elsewhere in the state of Veracruz, violence reigns supreme.

“The day we laid my daughter to rest they killed a 26-year-old doctor, they stole his pick-up truck. The vehicle has just turned up a few streets down from here with a body inside. Every day, somebody gets murdered,” she says.

The 22-year-old Génesis was in her last semester of a communications degree at Universidad Veracruzana. On September 29, sometime after 4.30pm, she went missing along with three other youths: Leobardo Arano, 24, who had just graduated in accounting, and the Technology Institute students Octavio García Baruch and Andrés García.

Pressure from their parents and a high crime rate in Veracruz, where homicides have doubled over the last year, drew media attention to the case. But it wasn’t until October 8 that relatives heard back from the prosecutor’s office.

“There were five bodies. The men had been mutilated [...], but the prosecutor told us that our daughter had been respected to some extent, and that her body was intact,” says Ramona.

Three of the students, including Génesis, were among this group of bodies – the other two belonged to a taxi driver and an unidentified man. The case of the last vanished student, Andrés García, was being handled separately as he was reported missing at a later date.

Authorities said that the corpses were found along a road in Camarón de Tejeda, around 70 kilometers from Veracruz. Octavio García Baruch had a brother who also went missing in October 2015.

In August 2016, Veracruz became the most violent place in Mexico, with 229 murders compared with 58 a year earlier. So far this year, 872 people have been assassinated, far above the figure for the entire year of 2015 (615).

The day we laid my daughter to rest they killed a 26-year-old doctor, they stole his pick-up truck

Ramona Ramírez, mother of Génesis Urrutia

“The rise in violence is the result of several factors: the dispute between criminal groups, and not just between the Jalisco New Generation and Los Zetas cartels, but also due to internal battles between Gulf groups, Los Zetas and other criminal organizations,” explains the security analyst Alejandro Hope. “Additionally, the increase in criminal activity is due to a disorganized government transition.”

Expelled by his Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and cornered by corruption allegations, state governor Javier Duarte on Wednesday announced that he is stepping down. Duarte, who had fewer than 50 days to go in power, is the target of a federal investigation into illegal enrichment.

The disappearance

On September 28, Génesis attended her last lecture in Communication Projects and Entrepreneurial Development. A girlfriend walked her to the bus stop, where they chatted for a while, according to the latter’s testimony.

After returning from Ecuador, where she spent a few months on a scholarship she got for her good grades, Génesis moved into in a house that her parents had bought for her in the area. She lived alone.

At 8.30am that morning, Ramona Ramírez phoned her daughter, like she did every day at the same time.

“She told me she was sleepy, she was not an early riser,” she recalls. “She wanted to be a model, but I never let her go into that line of work after high school.”

A popular girl at school, Génesis was a fan of chess and of books by Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes. She was also helping a foundation that finds homes for stray animals, and had plans to get a graduate degree in Spain.

After getting up that morning, Génesis wrote to a photographer friend to wish him a happy birthday, and at 11.40am she sent another message to her mother: “Mom, I love you. Have a wonderful day at work.”

Nobody saw her at university that day even though she had classes. “I called her at 3pm, but her phone went straight to voicemail,” says her mother.

At 4.13pm, Leobardo Arano logged onto to the social media app SnapChat and posted a picture of the two of them inside a room. Génesis’ neighbors saw her walk out of her house in the company of two young men at 4.30pm. All three of them walked into a store and came out with some food.

A witness said she saw Leobardo running at 5pm along Díaz Mirón Avenue, a popular thoroughfare just minutes away from the Boca del Río campus. According to this testimony, he was running away from two armed men, although security cameras did not pick up any foot chases in the area.

They were never heard from again. Génesis’ mother called her at 11pm and then again next morning, but got no reply. The prolonged silence raised the alarm.

Insecurity

Besides the rise in violence, Veracruz is steeped in economic ruin. A “for rent” sign hanging from an empty building across from the port is a metaphor for the decadence of a city that was once a beacon of hope for Spanish refugees, back in the 1940s. These days, downtown Veracruz is falling apart and the violence keeps the tourists away.

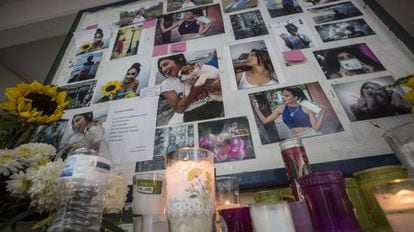

Back at the Communications School at Universidad Veracruzana, Génesis’ fellow students have erected a memorial with photographs, messages, candles and flowers. On October 3 they organized a march to demand that authorities find her alive. Now, they all denounce the violence.

“We hardly go out to bars,” says Benjamín, another communications student. University authorities declined to talk to this newspaper out of fear. Asked what they are afraid of, a student replies: “It’s something that’s been established, but we don’t know how. It has no name, position or face.”

English version by Susana Urra.