The Spanish role in the French Resistance

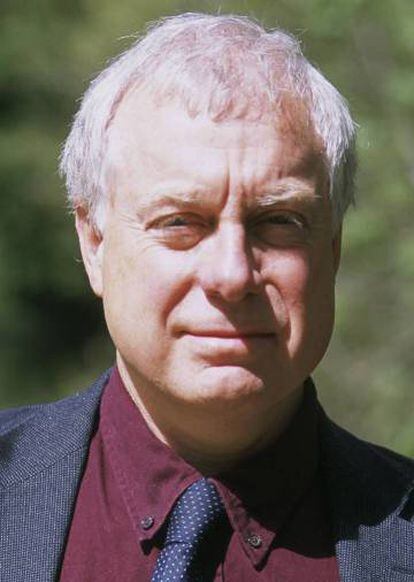

British historian Robert Gildea deconstructs the official version of events in his new book

The story that France constructed for itself after World War II goes like this: the country was liberated by the Resistance with some help from the Allies, and save for “a handful of wretches,” to use the words of General Charles de Gaulle, the rest of France’s citizens behaved like true patriots.

But nothing could be further from the truth. In his new book, Fighters in the Shadows: A New History of the French Resistance, British history professor Robert Gildea deconstructs this rhetoric, drawing up a detailed portrait of the occupation years with a critical eye.

The Civil War had really toughened us up

Vicente López Tovar, Resistance fighter

Rather than calling it the French Resistance, this expert on the subject likes to talk about “resistance in France” because of the enormous amount of foreigners who joined the fight against Nazism – including thousands of Spanish Republican fighters.

“France was defeated and occupied by Germany. When it was freed and unified again, a single history was created maintaining that the entire country attained freedom together under the leadership of De Gaulle; this story was propagated through medals, ceremonies and titles,” explains Gildea, a professor of Modern History at Oxford University’s Worcester College.

His book, which is coming out in a Spanish translation this week, takes a look at some of the forgotten heroes of that time: not just the Spaniards fleeing Franco, but also Jews from Poland and Romania, Communists and women, whose role as resisters has been consistently undervalued.

“The simplistic tale about the French national liberation only represents one part of the story, not all of it,” notes Gildea.

Fighters in the Shadows, which is scheduled for release in France in the spring of 2017, has already received critical acclaim in The Economist and The New York Review of Books, where it was reviewed by the great Vichy historian Robert O. Paxton.

Gildea, who has already published other works about the same period of history, admits that the ideal image of French society portrayed for years had already been questioned before by movies such as Louis Malle’s Lacombe Lucien, whose script was penned by Nobel winner Patrick Modiano.

But coming in at 650 pages, Gildea’s new work is the most comprehensive written to date with a critical approach to the 1940-1944 period in France. And the enormous success of a television series called Au nom du peuple français (or, In the name of the French people), which is already into its sixth season, evidences that the Resistance continues to be a delicate subject that does not become any less fascinating with the passing of time.

Fighters in the Shadows analyzes the great historical movements, but also comes down to street level, providing character studies of regular people who played their own part, big or small, in resisting the invaders.

“Scum of the Earth”

“We need to analyze what happened in France against the background of the fight against Nazism in Europe, but also in the context of the Holocaust and the Cold War,” says Gildea in a telephone conversation. “Many people in the Resistance had fought in the International Brigades.”

They were what the writer and journalist Arthur Koestler, who shared prison space with them, called “Scum of the Earth” in a book about his own experiences. They were people who had no place to go.

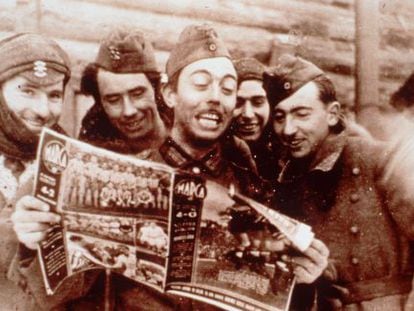

Many Spanish Republicans who had fought against Franco found themselves trapped in France at the outset of WWII. Their goal was to liquidate the Nazis first, then Franco. In fact, they led a failed attempt at invading Spain in 1944.

These Republicans were not just the members of La Nueve, the legendary brigade that was the first to enter Paris in August 1944, yet whose role was silenced for years. It was not until 2008 that street plaques were unveiled showing the path they took.

Gildea’s book also sheds light on combatants such as Vicente López Tóvar, who was born in Madrid in 1909, spent his youth in Buenos Aires, fought in the Spanish Civil War at the battles of Madrid and the Ebro River, and fled to France, where he helped organize the Maquis guerrillas. “The Civil War had really toughened us up,” López Tóvar told Gildea.

Spaniards on parade

The liberation of Toulouse, on August 19, 1944, was coordinated by forces led by Jean-Pierre Vernant, but Spanish Republicans played a major role in it. Southern regions such as Périgord and cities like Foix were entirely liberated by the Spaniards, a fact that De Gaulle never fully appreciated. Gildea says that the general rushed down to Toulouse because he did not wish to lose any control over the territory being freed of the Nazis.

The Spanish Republicans took part in the victory parade, wearing the German soldiers’ helmets, which they had repainted blue. When De Gaulle saw this, he reportedly exclaimed: “What are all those Spaniards doing parading with the Free French Forces?” To Gildea, this anecdote reflects the profound change that was taking place in the rhetoric about the Resistance.

English version by Susana Urra.