Drug dealers find a more lucrative trade: sea cucumbers

Demand in China is pushing illegal harvesters into the waters of southern Spain

The easterly wind has died down and the sea water is crystal clear. It is hard to find an empty spot on Cortadura beach, in Cádiz province. In the rocky area of Santibáñez, three youths in diving gear head out toward the shore with the firm intention of doing something illegal. They run back and forth carrying heavy baskets, and more than one beachgoer is heard wondering whether they might be carrying a shipment of hashish.

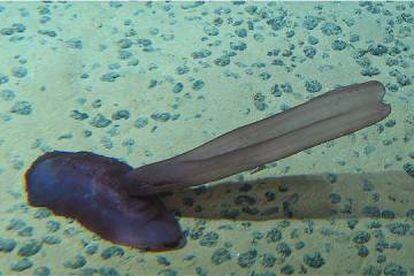

But then an anonymous citizen realizes what’s really going on, and calls 092 to ask the police to come stop the illegal harvesting of sea cucumbers. Three local officers show up and seize four baskets containing 200 kilograms of a small marine animal with a soft body known scientifically as Actinopyga echinites.

llegal harvesting has ballooned to such a degree that it is hard to find a single sea cucumber on popular beaches like La Caleta

So far this year, municipal officers have already confiscated a ton and a half of these echinoderms, which have inhabited Spain’s southern coasts for millions of years. Sea cucumbers do not bite or sting, and do not seem to move or defend themselves in any way. They simply live on the coast, drifting along with the tide and filtering the water.

Until three years ago, local fishermen only used them as fishing bait. But then word got out that sea cucumbers are a delicacy in China, where they are believed to have therapeutic and aphrodisiac properties. Since then, illegal harvesting has ballooned to such a degree that it is hard to find a single sea cucumber on popular beaches like La Caleta.

“If this pace keeps up, a year from now it’s going to be hard finding any at all; the species is becoming endangered,” says Ernesto Pérez, an official with the local police’s special services unit.

Pérez is one of the officers in charge of fighting the illegal harvesting of sea cucumbers. The regional government of Andalusia and Seprona, the Civil Guard’s nature protection department, make up the rest of the team.

But they are dealing with a well-established chain with many links that start with the local harvesters and end in China. So far this year, the Andalusian department of fisheries has initiated 69 proceedings in the coasts of Cádiz and Málaga; most of the fines are being slapped on the harvesters who physically pull the creatures out of the water.

High prices

José (an assumed name) is one of these harvesters. He runs online ads to attract Chinese buyers living in Cádiz. “I don’t pick many anymore because things have gotten really tough with the fines,” he admits. “I deliver them right on the beach, where a person pays me for the basket on the spot.”

José would rather not reveal how much he makes, but suggests that it is worth his while.

Legislation badly needed

If all those involved in the harvest of sea cucumbers agree on anything at all, it is on the need to end the legal loophole that is hurting the species.

The difference lies in how to do so. A decree issued by the Andalusian government in 2010 establishes that sea cucumbers “may only be captured in demarcated and classified production zones.”

This makes it illegal to harvest them recreationally. This activity entails fines of anywhere between €300 and €60,000. Francisco Javier Gutiérrez, the businessman with the licenses, says it is necessary to determine harvesting quotas.

José, the illegal harvester, agrees: “If the Junta [regional government] allowed for a controlled harvest, I would be first in line to go legal and become a self-employed worker.”

“It’s quite a lot, because I won’t risk it for peanuts. I’m the lowest link in the chain, and I suppose that prices in China must be frightfully high.”

Middlemen typically pay people like José around €70 for a basket, the local police said. These intermediaries clean, cook and dry the product before selling it to Chinese citizens residing in Cádiz, who in turn smuggle it into China.

“They place them inside suitcases and travel with them, acting as mules. They caught one recently at Barajas airport,” explains Francisco Javier Gutiérrez, one of just two businessmen in Spain with “all the required licenses” to do trade in sea cucumbers.

Gutiérrez sells up to five different types, with the cheapest one going for €48 plus tax per kilogram. He captures them off the Pacific coastline, where harvesting is allowed, and sends them to Japan. From there they get shipped to China, where “a kilogram commands around €500.”

But this price could shoot up to €1,500 if the specimen resembles the Japanese sea cucumber, which used to be harvested on the coast of Japan until the radiation from the Fukushima accident ruled out any further use for culinary purposes.

Gutiérrez complains that more is not being done against illegal harvesting. “Action is being taken against the harvester, but the people who buy are just as guilty as the people who sell. All you need to do is take a look online to find a bunch of illegal ads,” he adds.

Pérez, the local police officer, admits that they are only able to seize a part of the illegal harvest taking place on Cádiz's coast.

“We are highly aware that many more are getting away,” he explains. His department deals only with the first step in the illegal activity; it is up to Seprona to dismantle the sales network behind the trade in sea cucumbers.

From drugs to sea cucumbers

Pérez adds that three or four years ago, it was Chinese nationals who personally picked the animals out of the sea. “But it was very conspicuous and citizens who saw them would call us immediately,” he recalls.

That was when the Chinese turned to local harvesters instead. “There is an excess of demand, and exorbitant prices are being paid out,” says Pérez.

For the harvesters, the benefits are obvious. Besides the ease of capture, harvesting sea cucumbers does not entail prison terms if they are caught. There are, however, hefty fines that can reach €60,000. Regional authorities explain that this is because there is no specific regulation on sea cucumbers, which are merely classified as “a species that cannot be captured.”

The police officer also notes that several small-time drug traffickers have now turned into amateur harvesters, and admits that their own raids are “increasingly like drug trafficking raids.”

Typically, these harvesters go out at night on zodiac boats, bring home their loads and dry them on the balcony. “Being private property, it is hard to get a judge to grant a search warrant for an administrative violation,” adds the officer.

Sign up for our newsletter

EL PAÍS English Edition has launched a weekly newsletter. Sign up today to receive a selection of our best stories in your inbox every Saturday morning. For full details about how to subscribe, click here.

Instead, the local police rely on citizen cooperation. People, say Pérez, “are highly aware of how decimated the species is.”

Meanwhile, José will continue to risk a heavy fine to bring home sea cucumbers. “There is no work, so you hold on to anything you can find,” says the young man to justify his actions.

Pérez has heard this argument before, but he is not sympathetic.

“They are scared of immediate consequences, and this carries no prison terms,” he says. “But they are not aware that they are slaves to a ring, and that they risk mortgaging their entire lives to a fine that they will not be able to pay off.”

English version by Susana Urra.