“Brando was a pussycat”

Retrospective of veteran US photographer Steve Schapiro’s work goes on show in Zaragoza

There was a time in Hollywood when it was still possible to access the likes of Robert De Niro, Francis Ford Coppola and Robert Redford directly, without having to go through an endless list of agents, PR executives, stylists, and press officers. There was also a time when a photographer could spend weeks on the road during an election campaign with a politician such as Robert Kennedy, without any interference from advisors saying when and where pictures could be taken, and when they could, for example, walk into the hotel room of Martin Luther King, Jr. just hours after the civil rights leader had been murdered. The 1960s and 1970s were a very different time, as an exhibition of the work of veteran US photographer Steve Schapiro in Zaragoza demonstrates.

You just have to be a fly on the wall, making yourself invisible so the subjects can be who they really are”

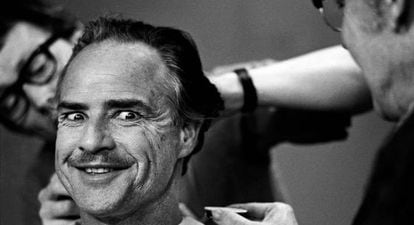

The exhibition, which comes under the banner of this year’s PhotoEspaña photography festival, shows the many sides to the 81-year-old’s work. Schapiro’s show business photos includes a shot of Marlon Brando gurning for the camera while a makeup assistant prepares him for his role in The Godfather. “Brando was a pussycat, I never had any problems with him. The problems came when he had to learn his lines,” says Schapiro, who is still working hard today, from his home in New York.

He recalls his first meeting with the star in his dressing room. “Heee taaaalked reeeeealy slooooowly, like this,” says Schapiro doing his best Brando impersonation, “but a few minutes later he came out, and there were dozens of people around who wanted to watch the scene being shot. I saw the electricity in his eyes, the strength of a young man. I knew at that moment that he would be huge in the film.”

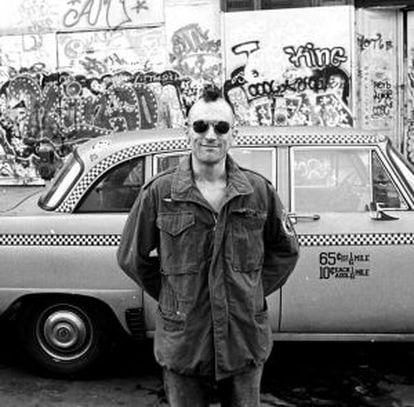

But Schapiro’s recollections of the shoot for Taxi Driver are very different. While everybody on The Godfather was relaxed and easygoing, the tension was palpable over on the Scorsese set, even between scenes. “You could see Scorsese sitting there, the movie going round in his head, and De Niro was just so into his role, his character, that he couldn’t shake it off,” says the photographer.

This is the first time that these photographs have been seen in Spain. “It’s an example of the artist moving into second place,” says Mario Martín, the curator of the exhibition. “Those photographs were immediately iconic, and at that time, nobody cared about who had taken them. Now the market is looking for names behind those photos.”

Schapiro started out trying to emulate his idol, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and learned from W. Eugene Smith. From the beginning he has always applied two maxims: that the photographer must be invisible to the subject, and that your next shot must be better than your last. “It is fantastic to have had the opportunity to meet those people and be in those places. At that moment you just have to be a fly on the wall, making yourself invisible so that the subjects can be who they really are.”

Over the course of his career, Schapiro has captured some of the most important events in US history. In 1965 he accompanied Martin Luther King, Jr. during his march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to demand black voting rights. Three years later, he was taking photographs inside the Memphis motel room where King was murdered. “They allowed me into the room where the shot had been taken from, I saw the bathtub that the assassin had stood in to shoot out of the window. You could see the groove in the window frame where the rifle had rested, and on one of the walls, a dirty handprint.” He then went to King’s room, where nothing had been touched since he had left it hours earlier. The television was still on, a suitcase was open, coffee cups sat on a table. “It seemed very symbolic, all his material things still there, but the man had gone.”

Schapiro also accompanied Robert Kennedy during his election campaigns: “It was fantastic to be able to share some moments in that difficult life,” he says. Of Andy Warhol, he mainly remembers his extreme shyness and fantastic powers of observation. “When you have to work with people with so much talent and charisma, a kind of collaboration takes place between the photographer and the subject. This happened with Magritte: we connected immediately, although I only exchanged a few words with him.”

Decades on from those iconic images, Schapiro continues to work. He is about to publish a book titled Bliss, about the current hippie counterculture, based on photographs taken at music festivals in the United States, Ireland and Hawaii. He sees the project as a return to his roots: “There isn’t much difference between photographing the real world and the world of movies. In both cases, I am looking for emotion, for that special moment.”

Schapiro: Retrospective. Until August 28 at Centro de Histórias, Plaza de San Agustín, 2, Zaragoza. Click here for more details.