Subterfuge: 25 years underground

The influential record label is celebrating its quarter century with a festival reuniting its past signings

In 1997, Dover, then an unknown four-piece from Madrid, became the group of the moment. Their first record, released in 1995, had barely sold 5,000 copies. But the next, Devil Came to Me, was the best-selling Spanish record of the late 1990s, shifting half-a-million copies to become the country’s equivalent to Nirvana’s landmark Nevermind five years earlier in the United States.

The success not only changed Dover’s fortunes, but also those of the record label that had released Devil Came to Me, Subterfuge. “We’ve always said that our success story wasn’t so much Dover, as surviving Dover,” say Carlos Galán and Gema del Valle, who founded the label in 1989, sitting in their offices in Madrid’s downtown Chueca neighborhood. “We had no idea of the scale of things. I remember that in September of 1997 they played in San Sebastián. There were 12,000 people. The local promoters couldn’t believe it. So what we did was print a load of flyers and go and distribute them at the door while people were queuing up to get in, rather than drinking champagne in the VIP zone,” says Gema.

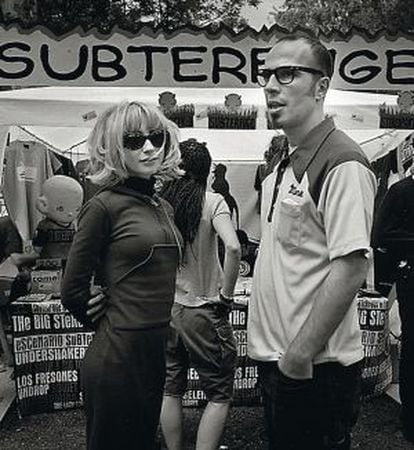

This year, Subterfuge is celebrating its 25th anniversary with a series of events that includes a two-day festival in Madrid’s Matadero arts center that kicks off on June 20. Around 30 bands that at one time or another have recorded for Subterfuge will be playing, including Marlango, Dover, Ellos and Fangoria, along with a few others who are part of the story and have decided to get back together for the occasion – Cycle, Killer Barbies, Los Fresones Rebeldes, Australian Blonde and Najwajean – as well as current signings McEnroe, Neuman, and Arizona Baby.

Their story’s like that of a rock band. They started from scratch, hit the big time, then went back to scratch”

“Their story is like some legendary rock band’s,’’ says Paco from Neuman. “They started out from scratch, hit the big time, and then went back to scratch. There have been ups and downs, but they have kept going.”

Javier Vielba of Arizona Baby hadn’t even started school when the label got going: “They had this fanzine, like photocopied and stuck together. It was amazing.”

Some of those fanzines will be on display at an exhibition that opens on June 12 at the Palacio de Cibeles cultural center in Madrid. Carlos describes himself as a “magpie” and has kept just about everything he has produced. “When we started out we didn’t know how to make records, so I made fanzines. Subterfuge was a way of talking about what we loved. We had no idea how long it would last,” he says.

In 1989, he was 21 and studying art history. Gema del Valle was still at high school. Since then she has gone on to handle the label’s public relations, and knows the Spanish record industry better than anybody. For all its chaotic and amateurish exterior, Subterfuge has always been a very professional operation, setting it apart from most other players in Spain’s independent record scene.

What is an independent record label? Selling records is about economies of scale, and for decades the industry has been dominated by a small group of labels with branches in every corner of the world. Now the multinationals have been reduced to three: Sony, Warner and Universal. Everybody else, from some kid in her bedroom to a player that can sell six million copies, are the independents. In other words, an independent is every company that isn’t a multinational.

These days record companies, independent or otherwise, are no longer the forces they once were. But back in 1989, things were different, says Gema. “This country was a musical wasteland. There was the generation of rock and punk musicians that had emerged during the movida [the cultural explosion that followed the end of the Franco dictatorship], in the early 1980s, and that was it. We started out recording the groups that were to hand, they were friends.” This was the label’s rock period, reflected by its gory fanzines and obsession with horror and schlock movies: a far cry from the political correctness of today. But little by little, the label changed: “Our philosophy has always been the same: if we made any money from the fanzine, we made a single. If the single made any money, we made an LP. We didn’t make records to make money, we made money to make records,” explains Gema.

If we made money from the fanzine, we made a single. If the single made money, we made an LP”

The label’s first success came in 1993, with its 37th LP, Pizza pop, by a trio from Gijón called Australian Blonde. Change was in the air. The record included a track called Chup chup, which thanks to a good relationship with a young A&R man at RCA, was used as the main song in Stories from the Kronen, director Montxo Armendariz’s movie about Spain’s Generation X. The record became a hit, the first of the indie generation of the 1990s. As a result, Subterfuge signed a distribution deal with RCA. “It was a lesson in how to do things,” says Carlos Galán “We had allies within RCA, and so it was easy, despite being the first.”

As a result of this success, many people in Spain believe that Subterfuge, like most independent record companies, is always on the lookout to find a group that nobody has heard of and pass them on to a major record label. “That is not our philosophy. In 25 years that has only happened in five cases: Australian Blonde, Dover, Fangoria, Najwa Nimri and Marlango,” insists Gema. “You can’t start fighting when you find yourself in that situation. Our aim is not to let people know about a band, and then for them to take care of themselves; we want them to stay with us forever, like Sexy Sadie or Mercromina. But life is chance and circumstance. If something works, the big fish will come looking around. And if a group wants to go, they are going to go, however difficult you make it. Look, if there is one thing that we are happy about, it’s that at this festival, all the groups that have left us and flown away and broken your heart after you’ve worked so hard for them, are all going to be on there, on stage, and it has been very easy to do that, all it took was one phone call.”

Some partings have been especially painful, such as that of Fangoria, the duo made up of Alaska and Nacho Canut, in 2002. When they signed to Subterfuge in 1998, they were little more than a curiosity; in 2001, two records later, Naturaleza muerta, produced by Carlos Jean, whom they had met through Carlos Galán, was riding high.

Alaska, who once worked as Gema’s assistant, tells her version of events: “Look, every group that leaves Subterfuge has done so following the same pattern. You initially sign up for three records, and when there is one left to do, you sit down and say: ‘Okay, let’s do this properly.’ Because everybody knows that the labels never put any money into the last record, so you always try to renegotiate. That is when Carlos sells his groups. Always, every time. If he says that is a coincidence, well, that’s fine. For everybody, right? For him and for all the groups.” Most of the groups that have recorded for Subterfuge have happy memories of their time with the label, describing Carlos and Gema as hard working and ambitious.

That’s ambitious in the sense of professional, not in the sense of people who will do anything to achieve success. And many in the business envy the duo’s ability to keep on reinventing themselves over the last quarter of a century. “If you look carefully, they have never repeated the formula: Dover was a Spanish rock group that sang in English; they then signed Los Fresones Rebeldes, which was pop in Spanish,” says Mikel López Iturriaga, a television presenter who worked as a music journalist in the 1990s. “They have recorded instrumentalists such as Carlo Coupé, as well as electronic music. They have always followed their instinct. They have been very successful at discovering the sound that goes with different periods. I think that the musical history of Spain would be very different without Subterfuge.”

“I think that Dover was the only time that we really lost it,” says Carlos Galán. “We moved into this enormous apartment, we set up a distribution company, and we thought we were smarter than everybody else. But it was a crazy time. We really thought we were the best thing since sliced bread. We hired 22 people, set up two companies ... Pretty much all the money we made from Dover disappeared during that business venture.”

Which isn’t to say that over the last decade, they haven’t enjoyed other success stories: Najwajean, Marlango, Cycle, and Vinila Von Bismark. But now times are tough, and they have to watch their outgoings, says Gema: “One thing is clear for me, though. You can’t set something like this up just with money. It requires hard, hard work, and above all, love.”