End to exile for a key political archive

Juan Negrín's granddaughter hands over 150,000 original documents for public consultation Historians eager to reassess last Republican leader's political role

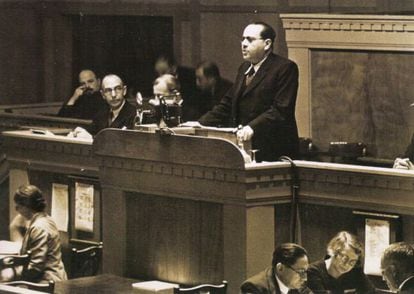

Wars never last as long as their secrets. It is likely that a few enigmas surrounding the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) will get cleared up next year, when a trove of highly relevant documents — whose mere survival is the stuff of fiction — gets released for public perusal. Beginning in February 2014, researchers will have access to thousands of official documents that Spain's last Republican leader, the Socialist Juan Negrín, transferred to France in several shipments to save them from destruction.

Carmen Negrín, the politician's granddaughter, made the decision to hand over the archive to authorities on his home island of Gran Canaria and open it up for research. After the Civil War and WWII, many differences of opinion within the Negrín family, and even a strange episode of breaking and entering, the Republican leader's legacy finally returned to Spain from France aboard a cargo ship, which dropped its historical load at the port of Las Palmas. Fittingly, the location selected by local officials to hold Negrín's documents is the former Caja de Reclutas, a building that was at the service of the military rebels in 1936.

Carmen Negrín, who is intent on restoring her grandfather's good name, handed over around 150,000 original documents relating to the war years and exile. For added safety, a copy of each piece of paper will be deposited at the French National Archives, while another copy is already stored at the state's Documentary Center for Historical Memory in Salamanca. But the use and custody of the legacy will fall to the Juan Negrín Foundation, a non-profit organization founded in Las Palmas in 1992. The archive is expected to open to the public in February.

Negrín managed to preserve material from the President's Office, the Treasury and the Defense Ministry. There are real gems in there"

And so Negrín's memory returns to the island where he was born in 1892 to a bourgeois family that put him through medicine school in Germany. His destiny seemed clear: a prominent scientific career during the course of which he trained Severo Ochoa, winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Medicine. Despite his family's conservative views, Juan Negrín's relatives ultimately paid a high price for his political prominence: his father was jailed for the crime of being related to him, and many of the family's assets were seized.

Although Negrín died in 1956 without leaving clear instructions as to what should be done with his archive, his granddaughter believes that she is following the wishes of the Second Republic's last president. "When he took the documents away it was with the idea that the Republic would return to Spain and that the papers would be returned to the state," she says. Carmen, who lived with her grandfather between the ages of three and nine, never once thought of making money out of his legacy. "This is not something that should be sold. It is very valuable and it has no price."

His political ideas were those of a statesman more than those of a devoted Stalinist

Historians agree. "This is a crucial archive," says Enrique Moradiellos, biographer of the Socialist politician. "Negrín managed to take out, and preserve practically intact, material from the President's Office, the Treasury Ministry and the Defense Ministry. There are real gems in there."

One such gem is the genesis of his memoirs, as well as official documents about the Spanish gold reserves that he transferred to Moscow in exchange for weapons to fight Franco's forces. The papers will also help to clear up his political ideas, which were those of a statesman more than those of a devoted Stalinist. "Although other refugees rejected it, he argued that Spain should join the Marshall Plan," says historian Sergio Millares, who also notes that Negrín respected religious freedom. "Following a chaotic period, he managed to impose some kind of order and issued instructions to normalize religious life." Until the 1990s, nobody outside the family had access to the archives. After that, the historians Sergio Millares and Gabriel Jackson, a US Hispanist specializing in the Republic, were allowed a peek. "We were the first to open up those bundles wrapped in 1939 newspaper," recalls Millares. "I was undoing knots, blowing off the dust, and crying with excitement."