The ultimate translation challenge

Three translators recount their experience of converting Proust to Spanish

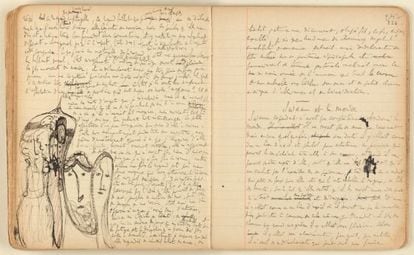

The story of the Spanish translation of Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time begins with a very young Pedro Salinas, who translated the first two volumes and part of the third at a time when their author was still alive.

But the poet of the Generation of 1927 left it at that, and the job was taken up over a period of 50 years by José María Quiroga Pla, then completed by Consuelo Berges, until a canonical edition was published by Alianza Editorial.

"When the rights to Proust became public domain, new French editions proved that a lot of water had run under the bridge of research. [...] It was necessary to re-read In Search of Lost Time with new eyes," says Mauro Armiño, who headed a monumental edition that was published by Valdemar in 2000. Armiño explains via email that the greatest challenge in translating Proust's work was the grammatical construction, "the tangle of phrasing, which despite appearances, is no game: it makes sense in itself."

"A text with such a peculiar and defined style as Proust's is an exercise that challenges the structure of the Spanish language and Spanish fiction, which has more of a penchant for realism and the external surface," he adds.

Even a French reader would not identify many of the references"

Yet once this humungous task was over, the translator came to a firm belief about "the absolute clarity of a text that only seems complicated because it is transferring into language the complex play of operations carried out by thought."

"Proust has a peculiar prose that is equally difficult to follow in the original language... this should not be softened up by the translation, and Amaya García and I put a lot of effort into preserving this difficulty," notes María Teresa Gallego, who co-translated a series of fragments of In Search of Lost Time for the anthology The Luncheon on the Grass, edited by Jaime Fernández.

Translating Proust was something she never thought she would get to do, given the recent proliferation of translations by others. "This is a dream for anyone who translates from French," she explains. In her case, she was obsessed with the translation into Spanish of the titles of volumes one and three in In Search of Lost Time: Du côté de chez Swann and Le côté de Guermantes. Gallego was not satisfied with Spanish readers asking themselves "What is Swann?" instead of "Who is Swann?" which is what French readers would have said. In earlier translations, the choice was "Por el camino de Swann" (On the road of Swann, which in English was rendered as Swann's Way). Du côté de, literally "on the side of," and more broadly "in the area of," is repeated 88 times in the novel, and functions as a musical leitmotiv.

"The challenge was finding a turn of phrase that could be used in Spain in each and every one of those cases, and not just to preserve the parallelism of the titles," say the translators Gallego and García.

Proust challenges the structures of Spanish language and fiction"

Mauro Armiño's translation for Valdemar comes with over 500 pages' worth of introduction, photographs, dictionaries, notes and additional documents. "A reading of Proust is demanding, with the aggravating circumstance of the century that has elapsed: even a French reader will find it impossible to identify many of the historical, literary, artistic and even personal references included in the text. With the three dictionaries I prepared of real people who had a relationship with Proust and the novel, and of the characters, summing up their adventures throughout such a long period of action that branches out in so many ways, I tried to offer readers a chance at a comprehensive reading, not just of the narration itself but also of the context in which it was created," he explains.

While Gallego does not feel it is indispensable (though there is nothing against it) to have new translations made every generation, Mauro Armiño adds that "according to an unwritten rule, languages undergo notorious changes every 50 years or so that do not make them impossible to understand but do add a level of difficulty; they exude a slightly antiquated smell; a new translation takes care to air out the text, eliminate the moths and the layers of moss built up over time, and incorporate the evolution of customs..."

There is yet another recent translation of Marcel Proust's monumental work, released by Lumen in 2000 (coinciding with the Valdemar publication.) Carlos Manzano, who is accustomed to translating challenging authors such as Henry James, Henry Miller, Italo Svevo, Malcolm Lowry, Giorgio Bassani, Louis Ferdinand Céline, Evelyn Waugh and Marguerite Yourcenar, claims that In Search of Lost Time was one of the easiest jobs he has ever taken on.

"At the time I felt I had the necessary experience to undertake the task, and I was convinced that I could create a text in Spanish that would be the stylistic — that is, fundamentally syntactic — correspondence of the original, as its author would have created it had he been a native speaker of Spanish."