Adieu to literature’s errant knight

Philologist and 'Don Quixote' expert Martí de Riquer dies at the age of 99

Don Quixote, Tirant lo Blanc and Arthurian knight Sir Percival will all be feeling somewhat orphaned this week, following the death of philologist, Cervantes expert and dean of the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language Martí de Riquer at the age of 99 in Barcelona.

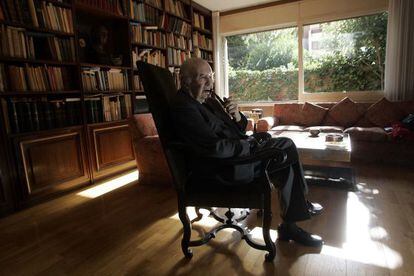

"I'm surprised that you are interested in talking about me," he told the 300-strong audience who attended the presentation of his biography in March 2008, in what was to be his last public appearance before he shut himself away in his home, languishing as wisely as he did silently, with his ever-present pipe and faraway gaze.

Perhaps within those walls he reawakened his marvelous imagination, which as a child he had showed off from a very young age. He was born in Barcelona in 1914, grandson of the artist Alexandre de Riquer and son of Emili de Riquer, whose early death drew him toward his mother's side of the family, which explains the fact that Castilian Spanish was his first language. "Bilingualism is convenient and advantageous," said Riquer, who as a young man had shown himself to be more of a supporter of Catalan autonomy, although always more in the cultural rather than the political sense.

Like Quixote, De Riquer, who was a member of the 17th generation of an aristocratic family (whom he wrote about in the delightful Quinze generacions d'una família catalana in 1979), lived a notable life. Despite studying business, the only thing to which he was able to devote himself were the literary classics, to which he was introduced via a collection of tales he received as a Christmas gift. This explains his incursion into literature at the start of the 1930s with such sharply humorous works as the play El triomf de la fonética and, what would become his first great philological work, L'humanisme català.

In 1937 he went over to Franco's side: "I was angry over the murder of certain friends"

The Spanish Civil War caught him, where else, but in a library - that of the Ateneu Barcelonès. During the first few months of the conflict he was assigned to the rescue service of the Catalan regional government's archives, where he performed a discreet and efficient job by intervening to prevent the execution by firing squad of the Falangist Lyus Santa Marina, in the same way that he later prevented the purging of Agustí Duran i Sanpere.

But in October 1937 he decided to go over to the side of the Francoists. "I was angered by the murder of some friends and had a certain affinity with the ideals of religion and order of the other side," he argued years later. He was assigned to the Third Requetés of Nuestra Señora de Montserrat, a unit of the Requetés Carlist militia, whose anthem he denied having written.

With The Divine Comedy in his backpack, he meandered through a war in which he ended up losing part of his right arm. He returned to Barcelona as a delegate of the Falange Propaganda Service and needed just a year, 1941, to get on with following his fate: he graduated in humanities from the University of Barcelona, where he stayed on as a teacher. Just nine years later he became a professor and in 1965 he was appointed a member of the Royal Academy, creating an army of disciples, who included Joaquim Molas and Antonio Comas, to whom he entrusted the continuation of his Historia de la literature catalana (History of Catalan literature), and Salvador Clotas. In front of them he thrashed out his impeccable works on the troubadours, first published in 1948 and later expanded in 1975, and on Tirant lo Blanc . Above all, though, he was behind a memorable edition of Don Quixote (1944) and the study Para leer a Cervantes (2003), which argued that Quixote was a comic adventure novel written by a competent reader of chivalric tales. He also worked on the pseudonymous Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda's sequel to Quixote and Arthurian legend (Perceval o el cuento del Grial). His passion for the medieval world led him to study Catalan and Spanish heraldry like few others and write the wonderful L'arnès del cavaller (1969). When Riquer spoke excitedly about medieval tournaments or a knight's panoply, he didn't hesitate in leaning forward in his seat to dramatize in more detail the way in which the victor finished off his fallen opponent.

Named the Marquis of the House of Dávalos and considered an "intellectual related to the regime and of noble family and monarchic tradition" by the Royal Household in 1960, he became a tutor to Prince Juan Carlos and ended up becoming a member of the future king's private council, as well as a senator by royal designation in 1977. Among the rewards he received were La Creu de Sant Jordi in 1992 and the Prince of Asturias Award for Social Sciences in 1997.

His political ideas did not stop him from winning the admiration of people as ideologically different as writer Manuel Vázquez Montalban, who paid tribute to him in his final novel. Riquer responded by admitting that it would have amused him to be a character in one of the author's crime novels, if possible, the murderer. Perhaps it was because he considered contemporary crime novels as the kind of literature that most resembled the tales of a 21st-century troubadour.