Spanish health system gets its money’s worth

In the United States, the results don’t justify the costs With a third less investment, Spain comes out better

The song says it clearly: the main things in life are good health, money and love. Leaving aside love, which is unpredictable, the relationship between wealth and one's physical condition is not as linear as one might think. True, a minimum layout is necessary to achieve wellbeing, and certainly, citizens of poor countries cannot hope to be the longest-living people on earth. But it seems that once a threshold of per capita health expenditure has been crossed (in OECD nations, this figure never falls under 500 euros a year), other factors come into play that influence health as much or more than the money flowing into the health system. These factors can be cultural, genetic, environmental, political or efficiency-related.

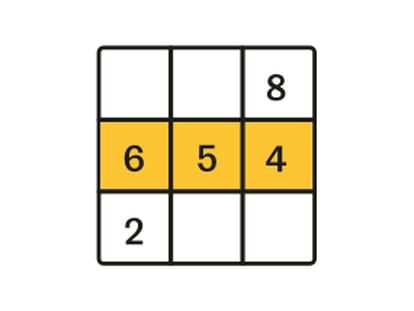

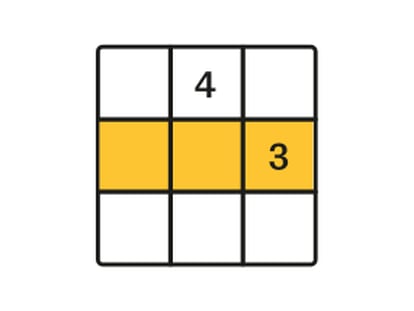

If it were simply a matter of cash, then Americans should be the healthiest, longest-living people on earth, not to mention the ones with the lowest obesity rates. The 8,233 dollars per capita (6,195 euros) that the US government spent on healthcare in 2010, according to OECD figures, is nearly three times what Spain spent the same year (2,300 euros), and 53 percent more than Norway.

This lack of proportionality is a matter of concern for US researchers, who see how the country's overwhelming financial superiority does not translate into health advantages for the American people. The latest warning came from a joint study by the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council.

One example of the inefficiency of the US system lies in average life expectancy. José Manuel Freire, a professor at Spain's National Health School, says this indicator is particularly significant. In the study, which analyzed 17 countries (the US and 16 of the world's most affluent nations), Switzerland placed first for male life expectancy (79.33 years) while Japan ranked at the top for female life expectancy (85.98 years, using 2007 figures). Spain is listed in ninth and fifth place, respectively. As for the US, it ranked last for men and second last for women, just ahead of Denmark.

Who is the best?

For Spain's health managers -- in the broadest sense of the term, from health ministers and commissioners to presidents of physician associations and so on -- the year 2000 stands out in golden letters. If the public health system was in need of a mantra, the World Health Organization provided it. For the first time (and as it turns out, the last), a WHO study dared rank countries by the quality of their health system. Spain, to everyone's surprise, placed seventh. Since then, there is no speech that fails to mention the fact that Spain has "one of the best health systems in the world," or at least it did 12 years ago.

What was even more noteworthy about that result was the fact that Spain ranked 24th in terms of per capita health expenditure. The list was peculiar to say the least. The top two health systems belonged to France and Italy, but the following ones were to be found in San Marino, Andorra, Malta and Singapore. Meanwhile, economic heavyweights like Britain, Germany and the United States ranked far behind (18th, 25th and 38th, respectively).

The list made waves throughout the world. If the WHO wanted publicity (it still hadn't become famous for its handling of the various flu outbreaks of the last decade), it had hit the jackpot. But the attention did not come for free -- criticism rained down on the organization. Would anyone really want to go to Malta for treatment if they had a serious condition? Would an American really get better healthcare in Oman, which ranked fourth on the list?

The media success became an academic conflict, because the truth is, there is no consensus on the best way to gauge the quality of health systems. There are universal indicators such as life expectancy, mortality rates, or number of years lost because of the system's deficiencies, but the WHO classification included other indicators such as free, universal access to healthcare, which penalized countries with state-of-the-art medical research but greater difficulty of access. The thing is, promoting free access to healthcare is one of the WHO's goals, and so the list reflected its own interests.

Nobody since then has dared publish a similar list. In Europe, the consulting firm Health Consumer Powerhouse, which receives EU funding, puts out a report once every two years. The study focuses on a highly relevant point: the role assigned to patients in national health systems. Spain tends to come out poorly, ranking 24th out of 34.

Death measurements are coherent with this picture: the US has the highest mortality rate per 100,000 inhabitants (504.9); Spain ranks 13th together with France (397.7); and Japan has the lowest rate (349.3).

The study includes many more indicators that confirm the trend. Freire, who besides being a scholar has also lived in the United States, says that "in many cases, the results of these indicators are linked to external factors."

"Obama's advisors have worked very hard on this, and they have focused on inequality," he adds, in reference to the Obama administration's attempt to overhaul the health system. "Of all intervening factors, relative poverty and social inequality are the two most influential, and in that sense the US is one of the most unequal countries in the world."

Juan Oliva, president of the Association of Health Economists, agrees. "Healthcare is one of the determining factors, but it is not the only one. Income (and its distribution), education, individual decisions (habits) and collective decisions (environmental and institutional elements) decisively influence the health of individuals and of populations, and they help explain why countries that invest fewer resources in the health system show better results," he says.

David Cantarero, director of the master's degree in Health and Social Services Management at Cantabria University, makes an additional point: "Regarding the question of whether more health spending is not always a better thing, let's be realistic: we should underscore that in any other economic situation than the current one, this debate would not even be taking place."

"In the last two decades (in Spain) we have observed that increasing public health spending lowers infant mortality rates and potential years of life lost, while it raises life expectancy," he says, yet adds that "there are certain expenditure levels after which, at a macro level, health results do not improve significantly.

"In the United States that correlation does not happen, perhaps due to their high administrative costs, their basically private nature, and the fact that healthcare and pharmaceutical expenses are 30 to 50 percent higher than elsewhere in the OECD," he adds.

US health experts are not unaware of these assessments, and they highlight the fact that people's habits are one of the chief health problems in the US. Although Americans smoke less now and have a lower tendency to binge drink than people in other high-income countries, they are the ones with the highest per capita caloric intake, the highest drug abuse rates, the lowest propensity to wear seat belts, the highest rate of road accidents involving alcohol consumption, and they are more likely to use firearms in acts of violence, the report indicates.

Another determining factor for the US health disadvantage is the country's higher poverty rates, especially of childhood poverty, and declining cultural levels, which influence health, the experts wrote.

The report not only seeks to raise awareness about the problem in a country where Republicans actively fought health reform, but also to underscore that a large part of the population remains uninsured. This issue was the target of Obama's reform plans, which wanted public health coverage for people without access to private insurance. In the end, Republican pressure led to a different result: that everyone would have private health insurance.

Nor did President Obama manage to make headway on primary care, even though "prevention and planning is where the US is really in poor shape," says Julio Zarco, academic director of Spain's Royal National Academy of Medicine. Zarco, who constantly shuttles between both continents, does not hesitate to state that the US is "like a third-world country in some respects."

"It is ruled by private insurers, which frown on prevention and health promotion," he adds.

Zarco, who was previously president of Spain's Primary Care Physicians Association (Semergen), insists that "planning and research require money, but that's not all. Later you need channels for that investment to start generating wealth."

Cantarero, of Cantabria University, adds that the "United States, which spends 17.6 percent of its GDP on healthcare, is a good example of how the country that spends the most in the world has even worst health indicators in some cases than Mexico, which spends 6.2 percent of GDP."

Oliva, of the health economists association, insists on the non-health factors. "Extending unemployment benefits in this crisis situation is a much better health [and welfare] policy than opening new hospitals," he says, in reference to Spain.

The diagnosis for the United States appears to be clear. What is not clear is how long things will remain this way. "With all the lives and dollars at stake, the country cannot afford to ignore this problem," reads the US report.

Zarco sums it up: "They are in an expansion phase for public policies. Over here, it's exactly the other way around."

Given the cost-cutting, it could be just a matter of time before US and Spain's health indicators switch places.