Nobody goes to jail for tax fraud

Should those guilty of fiscal crimes, particularly large corporations, pay more dearly for defrauding the state of its much-needed revenues?

Tax evasion has been punishable in Spain with prison for around four decades, during which time the authorities have caught dozens of companies and high-net-worth individuals trying to avoid paying contributions to the state's coffers. Often the figures involved run into the tens of millions of euros. Anybody caught trying to steal that kind of money from a bank would face decades behind bars, yet the state seems content merely to fine tax dodgers: of Spain's more than 80,000-strong prison population, just 90 people are behind bars for not paying their taxes.

At a time of ever-deeper cuts in public spending, and when every euro in revenue counts, shouldn't the government be looking to set an example to tax fraudsters, or is this a case of one law for the rich and powerful, and another for the rest?

The wealthy spend large amounts to prove there was no intention to defraud

"In Spain, you are considered clever if you manage to avoid paying your taxes"

Praxair is a highly successful US industrial gas multinational. In January, it finally agreed to pay the Spanish state 264 million euros for 13 counts of non-payment of taxes, running to 164 million euros in total. The company's CEO, James Sawyer, had been under investigation, but avoided prison.

"Putting somebody in prison for tax avoidance sends out a message, but so does a hefty fine," says Jesús Ruiz-Huerta, the former head of the Institute of Fiscal Studies, and a professor of Applied Economics at the King Juan Carlos University in Madrid. "In serious cases, prison sentences should be handed down, but as these are financial crimes, the most important thing is to recover the money. But at the same time," he says as an afterthought, "the wealthy tend to benefit from this approach."

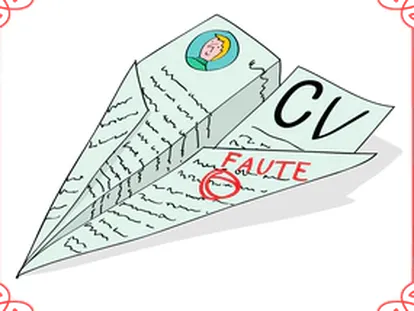

The law says that anybody who has deliberately tried to avoid paying at least 120,000 euros in tax is liable to a prison sentence. The problem the authorities face is that the wealthy are prepared to spend large amounts of money on lawyers to prove that there was no intention to defraud, and thus avoid the slammer.

Many tax inspectors themselves are critical of the current legislation. José María Mollinedo of Gestha, an association of tax professionals, says that a sliding scale is called for. "As things stand, 120,000 eurosis a very small amount for a large company," he says.

Proving that a company or an individual has deliberately tried to defraud the tax office is a long, complicated process. Many inspectors complain that investigating judges are too lax and that they do not always apply the same criteria as the tax office, sometimes throwing cases out for minor procedural discrepancies, a charge that Rafael Fernández-Montalvo, a magistrate at the High Court, rejects outright.

"That is a far from impartial assessment. The institutions of the state cannot be an interested party in an investigation, unlike the taxpayer. Tax inspectors should ask themselves if they are doing their job properly, and if they are acting completely within the confines of the law," he says. That said, he admits that there is a huge backlog of cases. "We are still dealing with appeals against rulings made in 2007, and which in turn are related to cases from the late 1990s."

One such case is broker Ava, which has just been handed down a relatively small fine after 13 years of rulings, appeals, and assorted legal shenanigans. "These are always very complicated cases and go very slow, because it is so hard to get evidence. Companies are now multinational, operating, for example, in several European countries, so often we have to ask for information from another state. We really need to move toward a European tax-inspection agency," says one inspector, who prefers to remain anonymous.

Spanish courts tend to take the attitude that it is only in cases involving very large sums of money that prison should be considered. Even in the event of going to jail for tax avoidance in Spain, the maximum penalty is five years. In Germany, France, the Netherlands and the United States, it is the intent to defraud, not the amount, that is considered. Again, penalties in these countries are much stiffer: up to 10 years in jail. In the United States there is no statute of limitations on tax fraud. In Spain, the limit is five years, besides the fact that the wheels of justice turn so slowly.

Nevertheless, the number of people who go to jail in the United States is proportionately around the same as in Spain. "In the United States, deals tend to be done, because at the end of the day, the state wants the money: the threat of prison is a bargaining position," says Luis del Amo.

According to the Gestha association, the culture of tax evasion has deep roots in Spain. In 2006, it called on the government to investigate why more than a quarter of all 500-euro bills were in circulation in Spain. It pointed to widespread corruption in the then-booming real estate sector, saying a significant number of property purchases were carried out using part cash payments to avoid tax.

"In this country, you are considered clever if you manage to avoid paying your taxes," says magistrate Martín Pallín. "We have to start educating children about the importance of paying taxes."