New trove of Spanish Civil War photographs emerges in Barcelona

An exhibition at the National Museum of Art of Catalonia shows moving scenes by Antoni Campañà, who concealed his pictures for decades inside a box and never told anyone about them, until his grandson discovered the prints in 2018

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/GBRQTT4PZ7N5EIUDM2S4KCAN7A.jpg)

To the list of great Spanish Civil War images captured by Agustí Centelles and Robert Capa, another photographer whose surname starts with a C must now be added: Antoni Campañà.

A native of Catalonia, Campañà took thousands of pictures of the conflict that raged between 1936 and 1939, but unlike his two famous colleagues, his lens focused not so much on epic events as on everyday life in the rearguard.

Most remarkably, his work documenting the war lay hidden for decades inside two red boxes in the garage of a house that was about to be sold. Campañà, who died in 1989, never told his family about its existence, and it was one of his grandchildren who stumbled upon a trove of images that represent a significant new contribution to Spain’s photographic records of that era.

Again, in a story mirroring the discovery of suitcases filled with previously unknown work by Centelles and Capa, a secret hideout was guarding documentary evidence of Spain’s recent past.

It was 2018, nearly three decades after Campañà's death in Sant Cugat del Vallès, and his house was about to be sold. One of his grandchildren was in the garage and found two red boxes containing glass plate negatives and around 1,200 developed images. The photos were inserted into cardboard frames with captions that allowed the family to identify more than 5,000 negatives that Campañà kept in another box that he had asked his children never to touch.

Campañà had hidden all his work because he felt hurt by the way the Franco regime had used it for purposes of propaganda and repression

Campañà was a Republican, a Catalan nationalist and a Catholic (he always carried an image of Our Lady of Mount Carmel inside his pocket). He had hidden all his work because he felt hurt by the way the regime of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco had used it for purposes of propaganda and repression. Some of the pictures were used by the new regime as evidence of crimes by the losers of the war.

Campañà was not a completely unknown figure in 2018. Around 200 of his photographs had appeared in newspapers and magazines. On the year of his death, La Caixa Foundation organized an exhibition with 90 images taken by him, of which only three covered the Civil War. The rest were about car races, soccer matches and festivities, his favorite subjects.

Now, a new exhibition at the National Museum of Art of Catalonia (MNAC) called La guerra infinita. Antoni Campañà. La tensión de la mirada. 1906-1989 (or, The Endless War. Antoni Campañà. Tension in a Gaze. 1906-1989), brings together 367 photographs, many of which have been developed from negatives for the first time, as well as documents exploring the career of a photographer who captured both sides of the conflict, and who was able to adapt to the normality that followed the end of the war.

This first retrospective – curated by Arnau González i Vilalta, Plàcid García-Planas and the grandson who discovered the pictures, Toni Monné – casts Campañà as a one-man band who was an artist, a photojournalist, an expert developer, a store manager, a representative for the Leica brand, a correspondent for the Spanish edition of Galería magazine and a scholar of the theory of photography who wrote articles and books on the subject. But despite his extensive and highly appreciated work, Campañà was left out of the history books.

With his Leica camera, he captured militia members such as the smiling young woman holding up a flag of the anarchist labor union confederation CNT in the middle of Barcelona’s La Rambla. It became an iconic image of the war after the CNT began disseminating it, but until 2019 Campañà did not get credit for it, because nobody viewed him as a Civil War photographer.

He also caught on camera scenes of Andalusian refugees who arrived in Barcelona in 1937, including one haunting portrait of a Málaga woman holding her child that is reminiscent of the iconic image of a migrant mother taken by US photographer Dorothea Lange during the Great Depression. A daily from Prague erroneously reported the Spanish mother and child as being in Guernica, the Basque city that was bombed by German planes in April 1937.

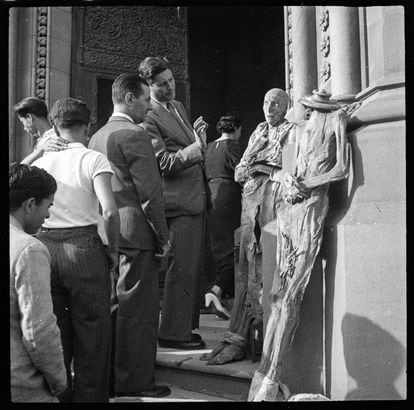

Campañà also captured the devastating effects of the Barcelona bombings, the hunger lines and the soup kitchens, the crowds that came out for the burial of the anarchist hero Buenaventura Durruti, the gruesome spectacle of mummified nuns exhibited outside churches following iconoclastic sacking by anarchists, and portraits of libertarians that were so eye-catching that the anarchists turned them into postcards.

His camera documented the protests by women demanding food outside the doors of La Pedrera, then the headquarters of the Catalan government’s provisions department; he recorded the tremendous violence reflected in scenes of bodies and of horses bleeding to death in the middle of Plaza de Catalunya.

“In some of those images, you can tell that Campañà feels uncomfortable about his subject matter, and that instead of taking pictures of dead bodies, he would rather show scenes of everyday life, the suffering of the people and how they adapted to circumstances,” says his grandson Toni Monné.

According to Monné, his grandfather had a “cheerful, dynamic disposition” but he was “traumatized by the war for the rest of his life, and this made him hide his own material, not talk about it, and not want to take advantage of it financially.”

Campañà photographed both sides, without committing to either one of them. In 1936 he photographed the anarchists marching toward the Aragón Front on Diagonal avenue, and in 1939 he also immortalized the retreat of the Republican army and the victory parades of Franco’s troops down that same avenue. He often resorted to the low-angle shots that he liked so well, as he did with his famous militiawoman.

When the war ended, Campañà began the journey into exile, but when he reached the city of Vic he decided to go back and turn himself in at the Bruc barracks. An engineer named José Ortiz Echagüe was there; the latter was also an acclaimed photographer of the pictorialist movement, and both men had worked together in their early years. Thanks to this, Campañà avoided reprisals and was allowed to keep working.

In one shot dated February 1939, just days after Barcelona was taken by the troops of General Yagüe, a young Falangist places a pin on the lapel of a young man in a suit who accepts with a smile. Campañà continued to work as a photojournalist even though his application to join the Official Register of Journalists was rejected.

In 1944, following the publication of a book by Francisco Lacruz named El alzamiento, la revolución y el terror en Barcelona (or, The uprising, revolution and terror in Barcelona) that contained photographs of his, Campañà decided to hide all of this material and never mention it again.

“Campañà could have been Agustí Centelles before Agustí Centelles, but he did not want to be the pictorial reference point of the Civil War,” says the curator Arnau González.

In spite of everything, Campañà went on to carve out a successful career for himself documenting the new Spain. He showed the industrialization of the country after the president of the automaker Seat – none other than his photography colleague Ortiz Echagüe – asked him to publicize the newly founded factory and the cars it produced. Campañà also became a leading sports photographer; between 1954 and 1957 he documented the construction of Camp Nou, Barcelona FC’s home stadium, and he partnered with Joan Andreu Puig to create CYP, the first brand to mass-produce color postcards for tourists.

Coinciding with its exhibition on Campañà, the MNAC has received 62 bromoil prints from his pictorialist period donated by his family. He perfected the technique in 1933 at a workshop that he attended during his honeymoon in Bavaria, where he was influenced by Rodchenko and central European esthetics. These are unsettling, vaporous images that turned Campañà into one of Spain’s most internationally acclaimed artistic photographers abroad, where he is known for Tracción de sangre (Blood traction) and Espantapájaros (Scarecrow), both from 1933, and bringing together his passion for the beauty of a vanishing rural world and the bold angles and framing borrowed from Germany’s Neues Sehen movement and Soviet constructivism. It is the same kind of framing that he used for his war pictures, where he always sought an artistic element.

And that is a key to understanding Campañà, for whom esthetics always prevailed over explicit narratives, even the cruel narrative of war.

‘La guerra infinita.’ MNAC. Palau Nacional, Parc de Montjuïc

From March 19 to July 18.

Opening hours:

October through April: Tuesdays to Saturdays from 10am to 6pm. Sundays and public holidays from 10am to 3pm.

May through September: Tuesdays to Saturdays from 10am to 8pm. Sundays and public holidays from 10am to 3pm.

Closed on Mondays.

Tickets: €12.

Exhibition only: €6.

English version by Susana Urra.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/RGYTI7MZ5RAKBKXL4SNR7UVNDI.jpg)